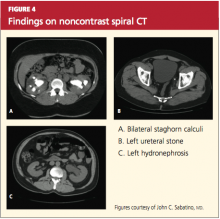

Hence, because of these limitations and the increasing availability of noncontrast spiral CT, noncontrast spiral CT is now the most commonly used and useful test in the diagnosis of kidney stones (sensitivity, 95% to 100%).32,36 Spiral CT accurately defines the size as well as the location of stones, and may additionally rule out other differential diagnoses (see Figures 4a, 4b, and 4c).

Historically, IV pyelograms and urograms were considered useful in locating urinary tract stones and diagnosing related complications,12 but these modalities carry additional risks related to IV contrast dye and radiation exposure. As a result, they have been almost completely replaced by noncontrast spiral CT because of ease of use and reduced risks.33

Stones may also be seen on renal ultrasound—particularly uric acid stones, which are radiolucent (see Figure 5). Ultrasound is appropriate for evaluation of patients whose exposure to radiation should be limited, such as children or pregnant women. In addition to plain film x-rays, renal ultrasound may also be useful for surveillance of stones.12

TREATMENT

Nephrolithiasis treatment varies between acute and chronic care. Acute care for nephrolithiasis involves management of acute pain and urinary obstruction, as well as patient stabilization. Chronic care includes prevention of recurrence and management of risks.

Acute Management

Patients who present with acute nephrolithiasis most often require fluid administration, aggressive pain management, and treatment for nausea or vomiting.31,32 Most ureteral stones measuring 5.0 mm or less will typically pass spontaneously within a few weeks,1,29 but larger stones usually require intervention—in some cases, surgery.

Patients should be hospitalized if they require IV fluids or pain management. Isotonic IV fluids should be given to increase the urine volume and facilitate passage of stones. Care must be taken to monitor fluids, as patients with kidney stones may have a limited ability to urinate (due to urinary obstruction and/or acute or chronic renal failure). Whenever possible, all urine should be strained to collect any stones for analysis.

One new strategy to assist with stone passage is medical expulsive therapy (MET), using calcium channel blockers (eg, nifedipine) or α-blockers (eg, tamsulosin).1,37 While there is conflicting evidence regarding the efficacy of calcium channel blockers for MET, one meta-analysis revealed a 29% improvement in stone passage with α-blockers.1,38

Pain management can often be accomplished with NSAIDs (eg, ketorolac, diclofenac).29 Since this class of medications can compromise renal function, however, they must be used with caution. Many patients require narcotic medications to control pain adequately.39-41 Antiemetic agents (such as the H1-receptor blocker dimenhydrinate42) should be administered to control nausea and vomiting.

Surgical and interventional management. Surgical intervention may be required if stones are too large to pass spontaneously (typically ≥ 8 mm); if they cause acute renal obstruction; or if they are located at a site with a potential for complications or can lead to persistent symptoms without evidence that they are passing.1,3 Renal obstruction should be treated aggressively to preserve renal function.

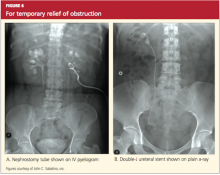

The type of intervention chosen depends on the size and location of the stone, as well as the presence or absence of obstruction. Stones that measure less than 20 mm are commonly treated with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (unless they overlie the sacroiliac joint), whereas patients with larger or more complex stones may require percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Nonobstructive or uncomplicated ureteral stones may be managed medically, whereas obstructive or complicated ureteral stones require placement of a stent or a nephrostomy tube until they can be removed by endoscopic surgery.29,43

Obstruction, which may be partial or complete, is more likely when stone size exceeds 10 mm.44 Signs of obstruction include sudden-onset, excruciating flank pain that radiates to the groin, along with nausea and vomiting (renal colic). Larger obstructive stones, such as staghorn calculi (as shown in Figures 3 and 4a), can present with symptoms of a urinary tract infection, mild flank pain, or hematuria.33

Presence of signs of obstruction or infection mandates emergent treatment. Infections of the urinary tract (as serious as pyelonephritis or urosepsis) should be treated with antibiotics: initially with broad coverage, according to the appropriate guidelines for urinary tract infections, then tailored to the results of urine cultures. Obstruction can be relieved directly by nephrostomy tubes (and/or stents) or by interventions in which the stone is removed and normal urinary flow is restored.

Typically, endoscopy is used for direct removal of stones that cause obstruction.44 Nephrostomy tubes and ureteral stents (see Figures 6a and 6b) are placed to relieve obstruction temporarily and provide an alternate route for drainage of urine. The goal is to prevent renal damage until the obstruction can be relieved. Stents can remain in place for several months, but nephrostomy tubes are associated with a higher risk for infection (because they are externalized), and duration of use should be limited to only a few weeks.12,29,38