DIAGNOSIS

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has developed classification criteria for the diagnosis of TA.22 The presence of three or more of the six criteria (age of onset ≤ 40, claudication of the extremities, decreased brachial artery pulse, > 10 mm Hg difference in systolic blood pressure between the arms, bruit over subclavian arteries or aorta, and arteriographic abnormalities) yields a sensitivity of 90.5% and a specificity of 97.8%. Although the ACR classification remains the most widely applied for TA, a limitation of its diagnostic criteria is its failure to distinguish patients with early nonocclusive disease.23

In 1988, the Ishikawa classification criteria were developed, with a modified version subsequently published in 1996.23 Considered superior to the original Ishikawa and ACR criteria based on its application in 106 patients with angiographically proven TA, the modified version has a reported sensitivity and specificity of 92.5% and 95%, respectively.23

With the modified Ishikawa diagnostic criteria, the presence of two major or one major and two or four minor criteria suggests a high probability of TA. The three major criteria consist of lesions of the left mid-subclavian artery and the right mid-subclavian artery and characteristic signs and symptoms of at least 1 mo duration. The 10 minor criteria are high ESR (> 20 mm/h); carotid artery tenderness; hypertension; aortic regurgitation or annuloaortic ectasia; and lesions of pulmonary artery, left mid-common carotid, distal brachiocephalic trunk, descending thoracic aorta, abdominal aorta, and coronary artery.

The diagnosis of TA is based on recognition of clinical findings suggestive of large-vessel vasculitis. Imaging of the arterial tree with CT, MRI, or angiography also demonstrates findings consistent with TA, typically including early-onset vascular wall thickening/enhancement.24 Late imaging studies may reveal arterial stenoses, occlusions, and aneurysms.

Several types of imaging modalities have been used in the diagnosis and management of TA, each with strengths and limitations. Traditional angiography is invasive and requires an arterial puncture. Large doses of radiation are used, exposing the patient to iodinated contrast material, which may be dangerous in patients with poor renal function. However, the primary advantage of traditional angiography is that it allows for interventions such as stent placement and/or angioplasty to be performed.24 Findings on angiography often include long, smooth, tapered stenoses ranging from mild to severe or frank occlusions, as well as collateral vessels or the subclavian steal phenomenon.24

CT imaging is very useful for assessing thickening of the arterial wall. In early TA disease, evaluation of vessel wall thickness may be identified prior to frank stenosis of the artery(s).24 The spectrum of findings on CT angiography includes stenoses; occlusions; aneurysms; and concentric arterial wall thickening affecting the aorta and its branches, the pulmonary arteries, and occasionally the coronary arteries.24

MRI does not require the use of iodinated contrast, nor is there radiation exposure. MRI also has the advantage of evaluating arterial wall thickening, which is often present prior to stenosis (similar to CT imaging).24 Findings of TA on MRI include mural thrombi, signal alterations within and surrounding inflamed vessels, fusiform vascular dilation, thickened aortic valvular cusps, multifocal stenoses, and concentric thickening of the aortic wall.24

Laboratory testing is neither specific nor sensitive. Hoffman and Ahmed studied multiple serologic tests and found that no test reliably distinguishes between patients with active TA and healthy volunteers.25 Increases in the acute phase reactants (ESR and CRP) support the presence of an underlying inflammatory process, and these laboratory tests may be useful in disease monitoring. The ESR and CRP often do not correlate with systemic symptoms or disease progression but are used in conjunction with the clinical exam and serial imaging to gauge treatment success and to monitor disease progression.5,25 Biopsy material typically is not available in the initial diagnosis of TA, but histologic examination at the time of a surgery or procedure is often undertaken to confirm the diagnosis.5

The differential diagnosis of TA includes connective tissue diseases associated with the formation of multiple aneurysms, such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.5 However, these diseases do not manifest with large vessel stenosis, the hallmark of TA. Infections known to cause aneurysms of the aorta should also be considered; these include bacterial, fungal, syphilitic, mycotic, and mycobacterial pathogens.5 Blood cultures are used to rule out bacterial agents. Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and venereal disease research laboratory tests (VDRL) will identify a syphilitic etiology. Fungal cultures or fungal serology will help to rule out a mycotic pathogen.

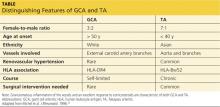

Autoimmune diseases that can mimic TA include Behçet’s disease, Cogan syndrome, the spondyloarthropathies, and systemic lupus erythematosus. These diseases are not associated with stenosis of large vessels, which differentiates them from TA.5 Giant cell (temporal) arteritis (GCA) may present very similarly to TA, as both diseases affect large arteries.12 The table provides distinguishing features of TA and GCA.26

Continued on the next page >>