How to proceed? What the experts recommend

In updated standards for the medical care of diabetes released in January 2013,11 the American Diabetes Association (ADA) calls for an HbA1c goal <7% for most nonpregnant adults with type 2 diabetes. This is in line with the 2012 International Diabetes Federation (IDF) guideline.12

The 2011 guideline from the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE),13 however, recommends tighter control—an HbA1c of ≤6.5% for most patients. For patients with diabetes of short duration, a long life expectancy, and no significant history of CVD, the AACE believes that this more aggressive goal has the potential to further reduce the risk of microvascular complications.

A less stringent target (eg, <8%) may be more appropriate for patients with a higher risk of adverse effects. That would apply to those with a history of severe hypoglycemia, a limited life expectancy, advanced micro- or macrovascular complications, or extensive comorbid conditions, as well as to any patient for whom stricter control is difficult to attain even with intensive therapy.13

Setting a BP target

In 2003, the 7th report of the Joint Committee on Prevention, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JCN 7) recommended a target BP <130/80 mm Hg for diabetes patients.14 Most major diabetes guidelines, including those of the AACE13 and IDF,12 echoed this recommendation. As noted earlier, JNC 8, published earlier this year, loosened the recommendation to <140/90 mm Hg.1 Although evidence has shown that treatment to a systolic BP <150 mm Hg improves cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes for patients with diabetes,15 no RCTs have addressed whether more intensive treatment to achieve a systolic BP <140 mm Hg provides further benefit.

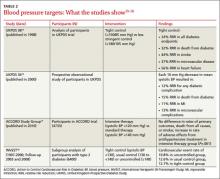

The BP of participants in the UKPDS has been examined, with patients with tighter control (<150/85 mm Hg) compared with those with less stringent control (<180/105 mm Hg). The tight control group showed a significant reduction in both death and complications related to diabetes, progression of diabetic retinopathy, and deterioration in visual acuity.15 Further investigation found that each 10 mm Hg reduction in systolic pressure was associated with a risk reduction of 15% for death related to diabetes, 12% for diabetes-related complications, 11% for MI, and 13% for microvascular complications.16

The ACCORD trial randomized participants to more intensive control (systolic BP <120 mm Hg, with a mean of 119.3) or standard therapy (systolic BP <140 mm Hg, mean 133.).17 After 4.7 years, no difference was found in the rates of MI, stroke, or death. However, a significant increase in the rate of serious adverse effects from antihypertensive treatment (including hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, hypokalemia, angioedema, and renal failure) occurred in the intensive control group.17

A subgroup analysis of patients with type 2 diabetes enrolled in the International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study (INVEST) evaluated systolic BP control and cardiovascular outcomes in those with preexisting coronary artery disease.18 Participants were categorized as having tight control if their systolic BP <130 mm Hg; usual control, if systolic pressure was between 130 and <140 mm Hg; and uncontrolled, if systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg. Those in the usual control group had lower risks of death, nonfatal MI, and stroke compared with those in the uncontrolled group, but little difference was found between patients in the usual control and tight control groups. The studies are summarized in TABLE 2.15-18

Next page: Interpreting the results >>