Alzheimer disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, affects more than 5 million Americans.1 Estimates suggest that by 2050, the prevalence could triple, reaching 13 to 16 million.1 To effectively care for patients with AD and their families, primary care providers need to be familiar with the latest evidence on all facets of care, from initial detection to patient management and end-of-life care.

This evidence-based review will help you toward that end by answering common questions regarding Alzheimer care, including whether routine screening is advisable, what tests should be ordered, which interventions (including nonpharmacologic options) are worth considering, and how best to counsel patients and families about end-of-life care.

ROUTINE SCREENING? STILL SUBJECT TO DEBATE

The key question regarding routine dementia screening in primary care is whether it improves outcomes. Advocates note that individuals with dementia may appear unimpaired during office visits and may not report symptoms due to lack of insight; they point out, too, that waiting for an event that makes cognitive impairment obvious (eg, driving mishap) is risky.2 Those who advocate routine screening also note that only about half of those who have dementia are ever diagnosed.3

Others, including the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), disagree. In its 2014 evidence review, the USPSTF indicated that there is “insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for cognitive impairment in older adults.”4

Mixed messages

The dearth of evidence is also reflected in the conflicting recommendations of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The ACA requires clinicians to assess cognitive function during Medicare patients’ annual wellness visits. CMS, however, instructs providers to screen for dementia only if observation or concerns raised by the patient or family suggest the possibility of impairment and does not recommend any particular test.5

Cost-effectiveness analyses also raise questions about the value of routine screening. Evidence suggests that screening 300 older patients will yield 39 positive results. But only about half of those will agree to a diagnostic evaluation, and no more than nine will ultimately be diagnosed with dementia. The estimated cost of identifying nine cases is nearly $40,000—all in the absence of a treatment to cure or stop the progression of the disorder.6

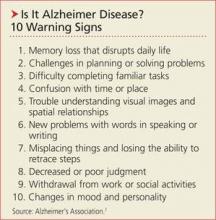

The bottom line: Evidence does not support routine dementia screening of older adults. When cognitive impairment is suspected, however, clinicians should conduct a diagnostic evaluation—and consider educating patients and families about the Alzheimer’s Association (AA)’s 10 Warning Signs of AD (see box, above).7 A longer version (www.alz.org/national/documents/checklist_10signs.pdf) outlines the cognitive changes that are characteristic of healthy aging and compares them to changes suggestive of early dementia.7

Next: How to proceed when you suspect AD >>