Case Report

A 66-year-old non-Hispanic white man with a history of adult-onset seizures, renal cell carcinoma, and nephrolithiasis presented to the dermatology clinic with numerous dark red, dry, scaling lesions on the lower legs, abdomen, back, thighs, and scrotum that bled easily. The lesions had developed 2 to 4 years prior to presentation. The patient also noted several dark blue lesions on the bilateral arms that had been present for several years.

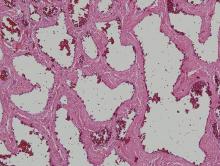

Physical examination revealed multiple black, keratotic papules on the bilateral lower legs (Figure 1), with similar lesions on the lower abdomen and lower back. Numerous dark red, scaling papules were present on the thighs and scrotum, and firm, 1- to 3-cm, dark blue nodules were noted on the bilateral arms (Figure 2) and right side of the forehead. Biopsy of papules from the lower right leg and back demonstrated angiokeratomas on pathologic review (Figure 3). Four separate biopsies taken from the left forearm demonstrated lobular and cavernous hemangiomas (Figure 4).

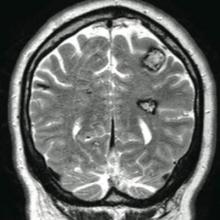

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for neurologic symptoms including adult-onset seizures at the age of 42 years. Recent magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed multiple areas of heterogeneous signal intensity with T2 hypointense rims consistent with cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) involving both cerebral hemispheres, the posterior cranial fossa, and the brainstem (Figure 5). Of note, the patient’s mother had been diagnosed with epilepsy in her 40s, but no other family history of a clinically or radiographically diagnosed neurologic disorder was reported.

This presentation of numerous CCMs and cutaneous vascular lesions prompted genetic testing for mutations in the 3 CCM genes. Bidirectional sequencing from a blood specimen confirmed a 1267C→T substitution resulting in an Arg423X nonsense mutation in the KRIT1, ankyrin repeat containing gene (also known as CCM1) on chromosome 7, which is a published mutation.1 No treatment of the cutaneous lesions was administered. The patient continued to be treated by a neurologist for the seizure disorder after genetic testing and counseling was complete.

Comment

Cerebral cavernous malformations represent collections of dilated, capillarylike vessels without intervening brain parenchyma,2 which can occur as a sporadic or autosomal-dominant condition with variable prevalence. Imaging and autopsy studies suggest CCMs may be present in 0.5% of the general population, with the incidence of clinically symptomatic disease being much lower.3,4 While sporadic cases are usually associated with the presence of a single CCM, hereditary cases generally display multiple CCMs5-7; studies indicate that most patients who present with symptomatic CCMs are in the second to fifth decades of life.3,8-10 The most common clinical manifestations of CCMs are headaches, seizures, and focal neurologic deficits due to cerebral hemorrhages.11

Three autosomal-dominant forms of familial CCMs are associated with several different heterozygous mutations in the CCM1 gene, which encodes Krev interaction trapped protein 1; the cerebral cavernous malformation 2 gene (CCM2), which encodes the protein malcavernin; and the programmed cell death 10 gene (PDCD10)(also known as CCM3), which encodes the PDCD10 protein.12-14 Although the precise pathophysiologic mechanisms linking these mutations with the resultant clinical phenotypes have yet to be fully elucidated, these genes are thought to play roles in angiogenesis as well as vascular maintenance and remodeling.11 Among non-Hispanic white kindreds with familial CCMs, 40% to 72% of kindreds were linked to mutations in CCM1, 20% were linked to mutations in CCM2, and 8% to 40% were linked to mutations in CCM3, depending on the series.13,15 The prevalence of symptomatic disease among gene carriers for kindreds linked to CCM1, CCM2, and CCM3 was 88%, 100%, and 63%, respectively.13 A specific founder mutation in CCM1 is thought to be responsible for virtually all cases of familial CCMs in Hispanic American individuals16 and up to 50% of this patient population are thought to have the familial form of the condition.5 As more is learned about the role of CCM gene mutations in the pathogenesis of CCMs, understanding how different mutations with different degrees of prevalence affect different patient populations will be important to help guide testing and perhaps treatment in the future.

![Figure 3. Histologic examination revealed dilated, blood-filled vessels in the papillary dermis with overlying acanthosis and hyperkeratosis consistent with an angiokeratoma (H&E, original magnification ×10 [inset ×4]).](https://cdn-uat.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/styles/medium/public/images/RTEmagicC_234f23e_Whitworth3.jpg.jpg)