A gram-negative bacillus of the Enterobacteriaceae family, Serratia marcescens is an organism known to cause bacteremia, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, endocarditis, meningitis, and septic arthritis.1 Unusual cases of cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis (NF) caused by S marcescens also have been reported.2,3 This entity has been initially described in immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised patients.4 Both community and nosocomial cases also have been reported.3

Case Report

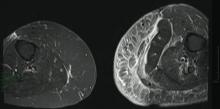

A 68-year-old morbidly obese woman with high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, chronic venous insufficiency, and left leg lymphoedema was referred to our emergency unit. She had pain and circumferential erythema with multiple abscesses of the left leg of 2 weeks’ duration. No history of trauma, ulcer, injection, or animal bite was noted. At the time of presentation she had no fever and vital parameters were normal. Empirical treatment with oral amoxicillin (6 g daily) and amoxicillin-clavulanate (375 mg daily) was started. Forty-eight hours later, inflammation, pain, and abscesses worsened (Figure 1A). Laboratory tests showed an elevated white blood cell count (15.9×109⁄L with 86% neutrophils [reference range, 4.5–11.0×109⁄L]) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (322 mg/L [reference range, <2 mg/L]). Human immunodeficiency virus serology was negative. Needle aspiration of an abscess yielded S marcescens. A second aspiration confirmed the presence of the same organism, wild-type S marcescens, which was resistant to amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, first-generation cephalosporin, and tobramycin but sensitive to piperacillin, third-generation cephalosporins, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and co-trimoxazole. Intravenous cefepime, a third-generation cephalosporin, was started. During the next 48 hours the patient developed severe sepsis with confusion, acute renal failure (creatinine: 231 µmol/L vs 138 µmol/L at baseline [reference range, 53–106 µmol/L), and worsening of skin lesions. Blood cultures were negative and amikacin was added. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a diffuse inflammatory process involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue that extended to the soleus fascia with no other muscle involvement or deep collection (Figure 2). Surgical debridement of infected tissues was performed (Figure 1B). Histologic examination revealed spreading suppurative inflammation involving the dermis and subcutaneous tissues. Clinical healing was obtained after 21 days of antimicrobial therapy. The debrided area required skin grafting 2 months later (Figure 1C).

| Figure 1. Erythema with multiple abscesses on the left ankle and leg at presentation (A), day 1 following surgical debridement of infected tissues (B), and 2 months later with complete healing following a skin graft (C). |

Comment

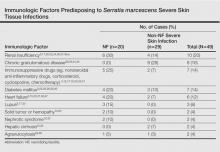

The most common causative bacteria of cellulitis are Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-hemolytic streptococci. Serratia marcescens is a rare but increasingly recognized pathogen of skin and soft tissue infections.5 The proposed pathogenic mechanism for skin necrosis during S marcescens infection is the bacterial production of large proteases (eg, deoxyribonuclease, lipase, gelatinase).6 Injection of purified proteinase from S marcescens into rat skin leads to increased vascular permeability, necrosis of epidermal tissue, dermal inflammation and edema, and infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the subcutaneous fat and muscle.7Serratia marcescens is ubiquitous in soil and water and it also may colonize the respiratory, urinary, and digestive tracts in humans. Cellulitis due to S marcescens secondary to iguana bites8,9 and snake bites10 or leech-borne cellulitis11 suggest that the oral cavity of these animals may be colonized. To date, 49 cases of severe S marcescens skin infections have been described, according to a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Serratia marcescens and skin, cutaneous, soft tissue, and cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis: 20 cases with NF3,12-28 and 29 non-NF cases8-11,29-46 (typical cellulitis presentation [n=8]9,11,35-38,40; abscesses, gumma, or pyoderma gangrenosum–like lesions associated with chronic granulomatous disease in childhood [n=7]29,44,45; painful nodules with secondary abscesses [n=6]31-34,46; acute bullous cellulitis [n=4]8,10,30; secondary infections of ulcers [n=2]35,40; abscesses in immunocompetent patient [n=1]41; and necrotizing skin ulceration [n=1]36). Lower extremities were frequently involved (NF cases, n=13; non-NF cases, n=16). Underlying immunosuppression was observed in 14 NF cases and in 17 non-NF cases. Predisposing immunologic factors are summarized in the Table. Local risk factors, including chronic leg edema, trauma, surgical wound, filler injection, and ulcer, were frequently reported in NF and non-NF cases,16,20,26-28,31,32,34,35,37,38,40,46 including our case. Surgery was required in 19 NF cases and in 7 non-NF cases. Serratia marcescens–mediated NF led to higher mortality (n=12) than non-NF cases (n=1). Other nonsevere clinical manifestations of S marcescens infection reported in the literature included disseminated papular eruptions with human immunodeficiency virus infection42 and trunk folliculitis.43 Our patient had many risk factors, including chronic edema, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal insufficiency, and chronic venous insufficiency. The potential presence of abscesses and necrotic tissue hinders antibiotic penetration at the infection site, and surgery should be systematically considered as early as possible in view of the high mortality rate of S marcescens cellulitis.