Teledermatology remains relatively limited in practice despite strong evidence supporting its use.1 A major impediment to its adoption is nonreimbursement.2,3 We sought to characterize business models that currently are in use for teledermatology through interviews with private and academic dermatologists.

The institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) exempted this study from review. We contacted the email lists of the American Academy of Dermatology’s Telemedicine Task Force, the American Telemedicine Association’s Teledermatology Special Interest Group, and the Association of Professors of Dermatology to identify dermatologists who have been reimbursed for teledermatology services. Inclusion criteria were dermatologists who were currently receiving payment for teledermatology services and members of teledermatology-related professional groups. Interviews were conducted by telephone and/or email using an interview guide, which included questions on teledermatology platforms and workflow models, reimbursement structures and amounts, and referrers. Individuals, institutions, and teledermatology platforms were anonymized to encourage candid disclosure of business practices.

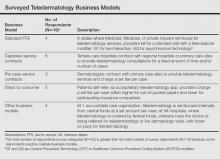

Nineteen dermatologists participated in the study. Most participants described business models fitting into 4 categories: (1) standard fee-for-service reimbursement from insurance (n=4), (2) capitated service contracts (n=6), (3) per-case service contracts (n=3), and (4) direct to consumer (n=5)(Table). There were other business models reported at Veterans Affairs hospitals and accountable care organizations (n=4).

Standard fee-for-service (FFS) teledermatology business models were frequently represented among respondents at academic institutions. With this model, providers used live interactive or store-and-forward teledermatology platforms to conduct virtual clinic visits and bill patients’ insurance companies directly. At some institutions, providers conducted live interactive teledermatology visits and also used store-and-forward teledermatology for initial screening before the patient encounter. Physician extenders at some referring sites (eg, physician assistants, nurse practitioners) were trained to photograph lesions, set up live interactive teledermatology equipment, and perform certain procedures such as skin biopsies. Referrers—often Federally Qualified Health centers, rural health clinics, or state facilities—contracted with the teledermatology site and sometimes paid a fee to join the referral network.

In another business model, teledermatology centers did not bill patients directly and instead received payment only from the centers’ participating referrers through service contracts. The subscribing institutions then could bill patients’ insurance companies appropriately. Service contracts among respondents were structured either to be capitated or reimbursed on a per-case basis. Capitated service contracts typically required subscribing institutions to pay weekly stipends of several hundred dollars or a percentage of an individual dermatologist’s salary (eg, 0.1 full-time equivalents) for consultations. Sometimes the number of consultations per time period was capped. In contrast, per-case service contracts involved per-case payments from referrers to dermatologists for teledermatology consultations. In one hybrid model, the subscribing institution paid an annual fee for a certain number of consultations per month with any additional consultations exceeding that number covered at a set fee per case.

Direct-to-consumer models, which were more common among private dermatologist respondents, used proprietary asynchronous teledermatology platforms to connect with patients. Patients generally paid out of pocket to participate, with fees ranging from $30 to $100 per case or less if the patient had participating insurance. One respondent contracted with a large private insurer to reimburse this service at a reduced fee.

Our study was limited by a small sample size; however, our goal was to detect and report different types of teledermatology business models that currently are in practice. The small number of respondents likely does not indicate poor participation; rather, it is probably reflective of our strict inclusion criteria. We sought to interview only dermatologists who were currently receiving payment for teledermatology services and members of teledermatology-related professional groups. Our strategy in this study was to cast a wide net to capture some of the few dermatologists who currently fit this requirement.

We anticipate that the standard FFS business model for teledermatology will expand slightly as more legislation incentivizing telemedicine is enacted. Currently, Medicaid reimburses for live interactive teledermatology in 47 states and for asynchronous consultations in 9 states, whereas Medicare nationally reimburses only for live interactive services in low-access areas.4 Additionally, 29 states and the District of Columbia have private insurance parity laws mandating that private plans cover and reimburse for telemedicine comparable to in-person care. Seven of those states just passed their legislation in 2015, with 8 more states currently considering proposed parity laws.5

On the other hand, the FFS model in general may actually limit the rate of adoption of teledermatology. Several of our study’s respondents pointed to dermatologists’ opportunity costs under the FFS reimbursement environment as a barrier to widespread adoption of teledermatology; providers may prefer in-person visits to teledermatology because they can perform procedures, which are more highly reimbursed. For that reason, a major driver of teledermatology adoption in the future may be the emergence of new, quality-based practice models, such as accountable care organizations.6