Results

Study Participants

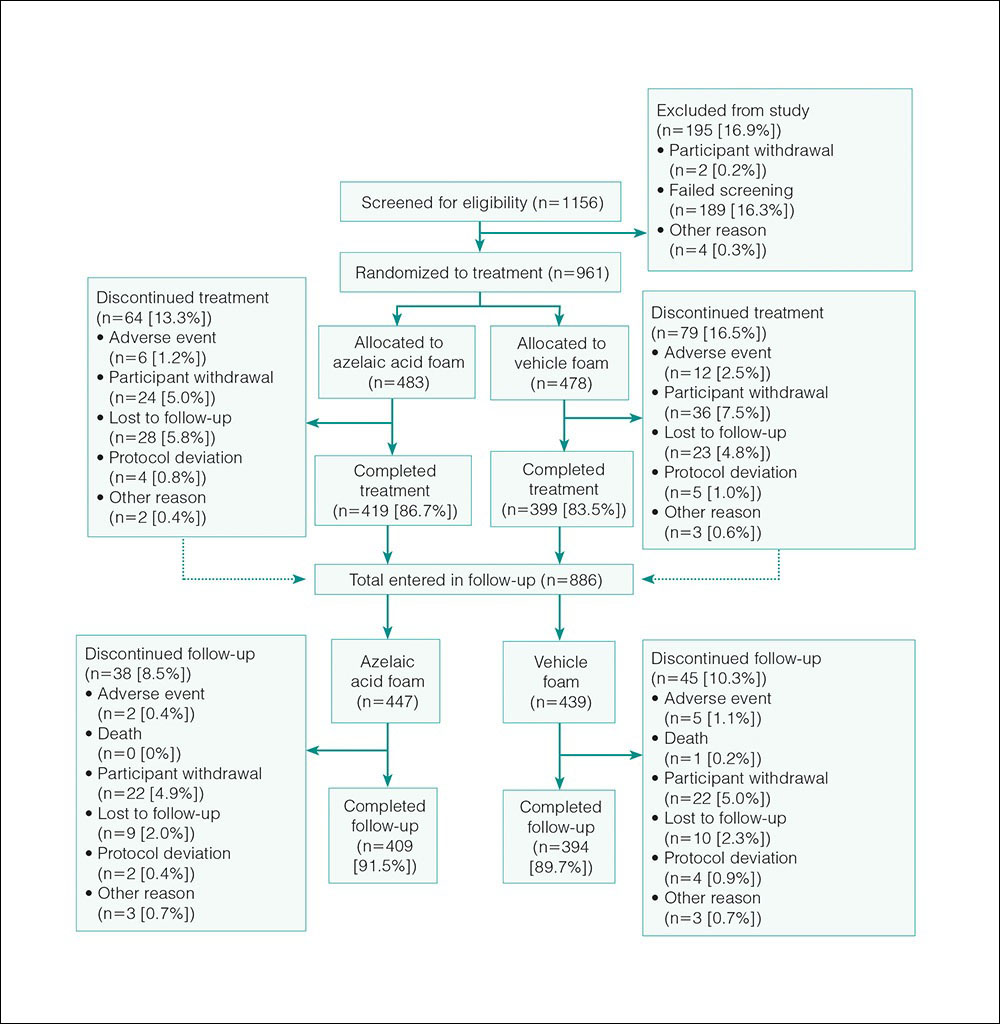

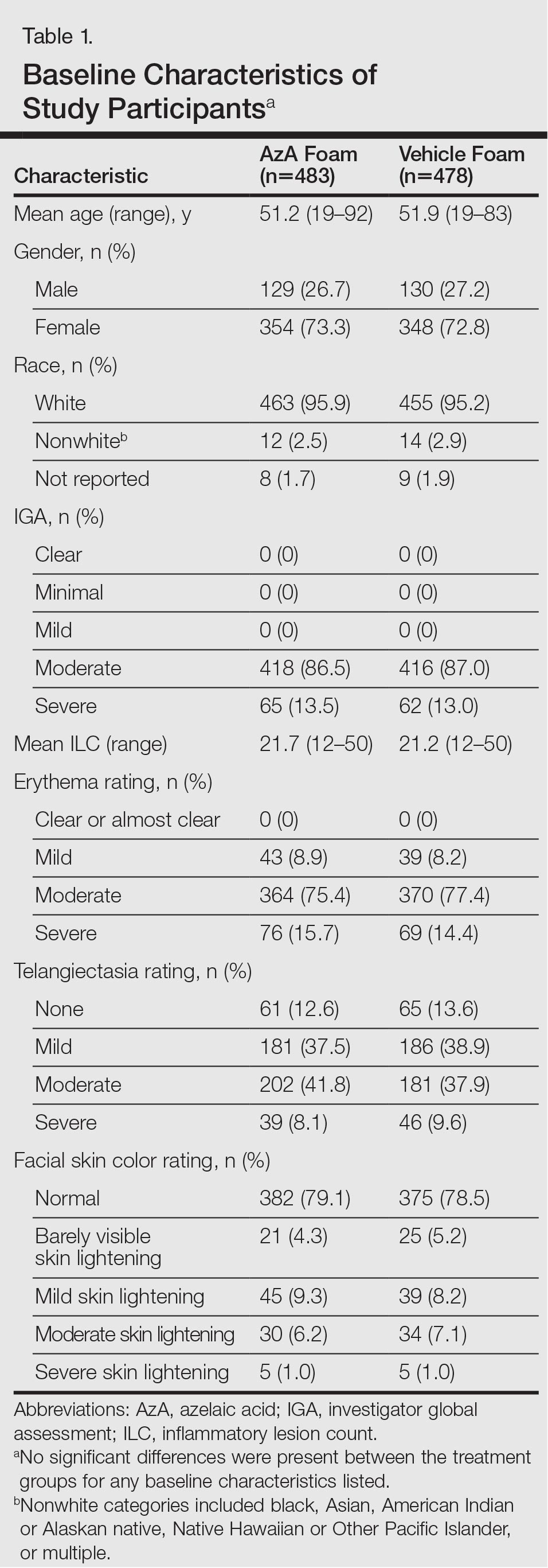

The study included 961 total participants; 483 were randomized to the AzA foam group and 478 to the vehicle group (Figure 1). Overall, 803 participants completed follow-up; however, week 16 results for the efficacy outcomes include data for 4 additional patients (2 per study arm) who did not formally meet all requirements for follow-up completion. The mean age was 51.5 years, and the majority of the participants were white and female (Table 1). Most participants (86.8%) had moderate PPR at baseline, with the remaining rated as having severe disease (13.2%). The majority (76.4%) had more than 14 inflammatory lesions with moderate (76.4%) or severe (15.1%) erythema at baseline.

Efficacy

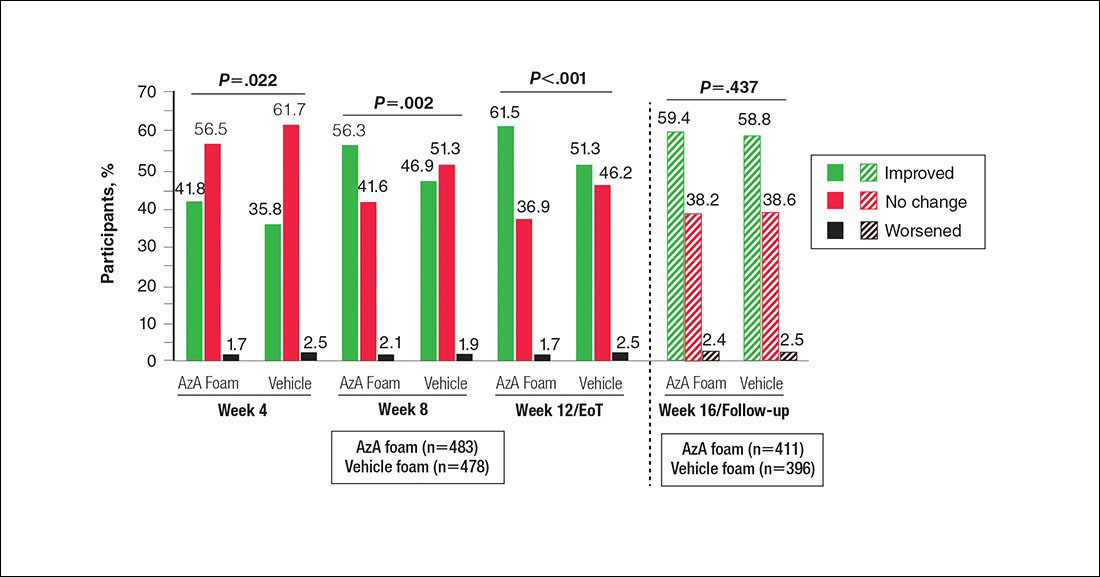

Significantly more participants in the AzA group than in the vehicle group showed an improved erythema rating at EoT (61.5% vs 51.3%; P<.001)(Figure 2), with more participants in the AzA group showing improvement at weeks 4 (P=.022) and 8 (P=.002).

Figure 2. Grouped change from baseline in erythema rating by study period. All values (1-tailed) derived from Wilcoxon rank sum test; week 12/end of treatment (EoT) value (1-tailed) derived from Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel van Elteren test stratified by study center. No study drug was administered between week 12/EoT and week 16/follow-up; last observation carried forward was not applied to week 16/follow-up analysis. AzA indicates azelaic acid.

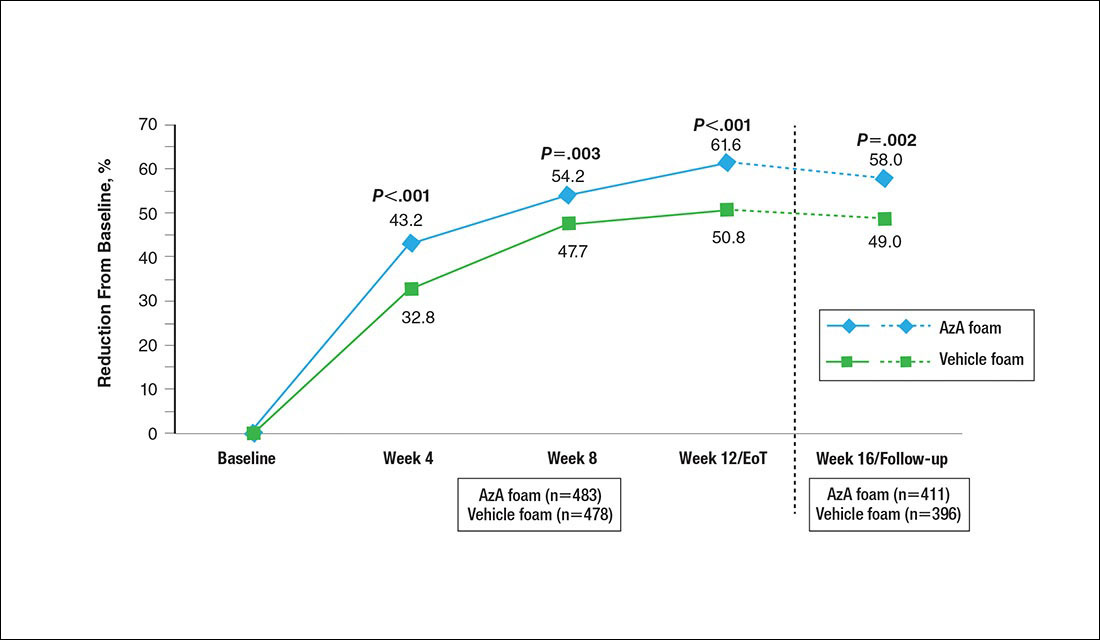

A significantly greater mean percentage reduction in ILC from baseline to EoT was observed in the AzA group versus the vehicle group (61.6% vs 50.8%; P<.001)(Figure 3), and between-group differences were observed at week 4 (P<.001), week 8 (P=.003), and week 16 (end of study/follow-up)(P=.002).

Figure 3. Mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory lesion count (ILC) by study period. Percentage change in ILC is nominal change from baseline to postbaseline in ILC divided by number of baseline lesions. All P values (1-tailed) derived from Student t test. Week 12/end of treatment (EoT) adjusted mean percentage reduction in ILC was 60.7% in the azelaic acid (AzA) group versus 49.5% in the vehicle group (P<.001, F test of analysis of covariance). No study drug was administered between week 12/EoT and week 16/follow-up; last observation carried forward was not applied to week 16/follow-up analysis.

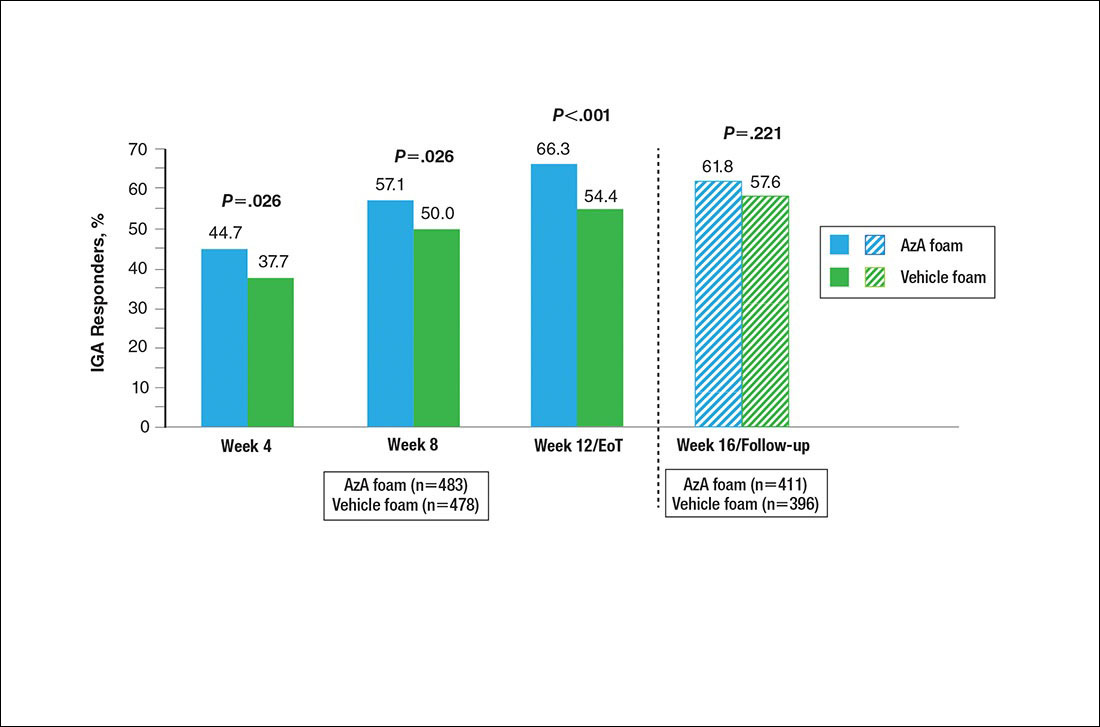

A significantly higher proportion of participants treated with AzA foam versus vehicle were considered responders at week 12/EoT (66.3% vs 54.4%; P<.001)(Figure 4). Differences in responder rate also were observed at week 4 (P=.026) and week 8 (P=.026).

Figure 4. Therapeutic response rate by study period. All values (2-tailed) derived from Pearson χ2 test; week 12/end of treatment (EoT) P value (2-tailed) derived from Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel van Elteren test stratified by study center.

No study drug was administered between week 12/EoT and week 16/follow-up; last observation carried forward was not applied to week 16/follow-up analysis. AzA indicates azelaic acid; IGA, investigator global assessment.

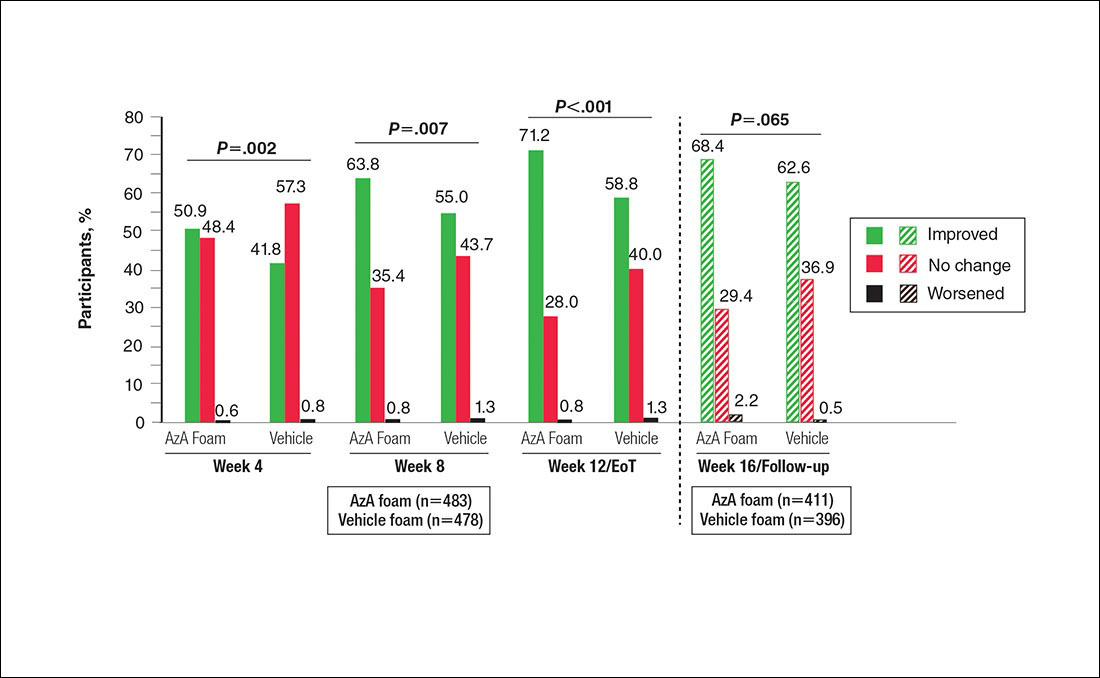

Differences in grouped change in IGA score were observed between groups at every evaluation during the treatment phase (Figure 5). Specifically, IGA score was improved at week 12/EoT relative to baseline in 71.2% of participants in the AzA group versus 58.8% in the vehicle group (P<.001).

Figure 5. Grouped change from baseline in investigator global assessment score by study period. All P values (1-tailed) derived from Wilcoxon rank sum test; week 12/end of treatment (EoT) P value (1-tailed) derived from Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel van Elteren test stratified by study center. No study drug was administered between week 12/EoT and week 16/follow-up; last observation carried forward was not applied to week 16/follow-up analysis. AzA indicates azelaic acid.

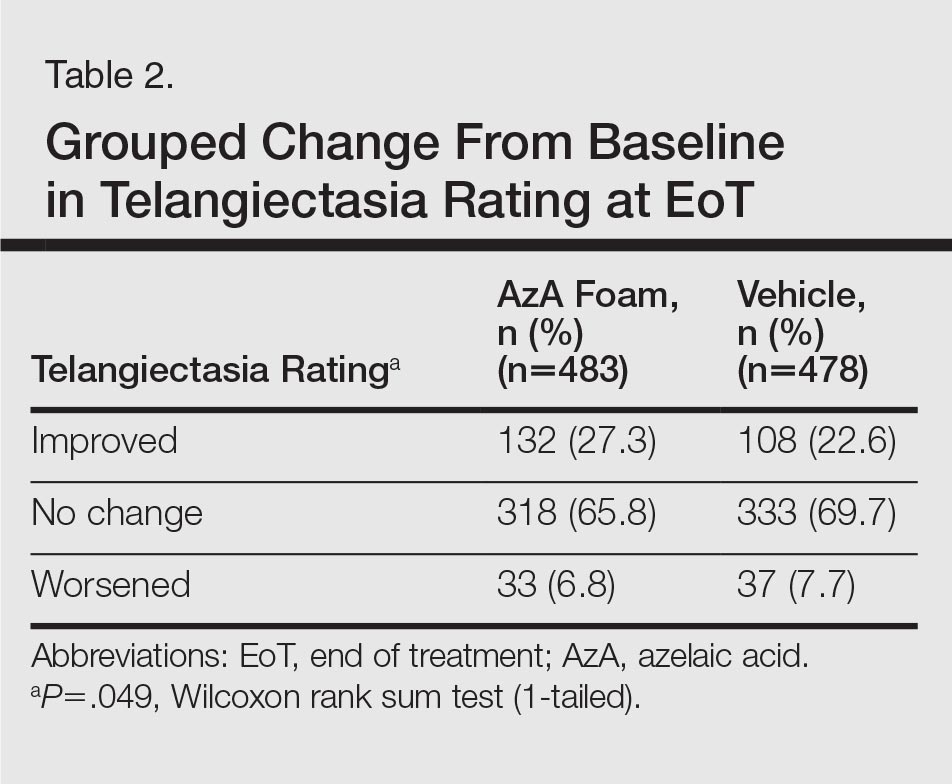

For grouped change in telangiectasia rating at EoT, the majority of participants in both treatment groups showed no change (Table 2). Regarding facial skin color, the majority of participants in both the AzA and vehicle treatment groups (80.1% and 78.7%, respectively) showed normal skin color compared to nontreated skin EoT; no between-group differences were detected for facial skin color rating (P=.315, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Safety

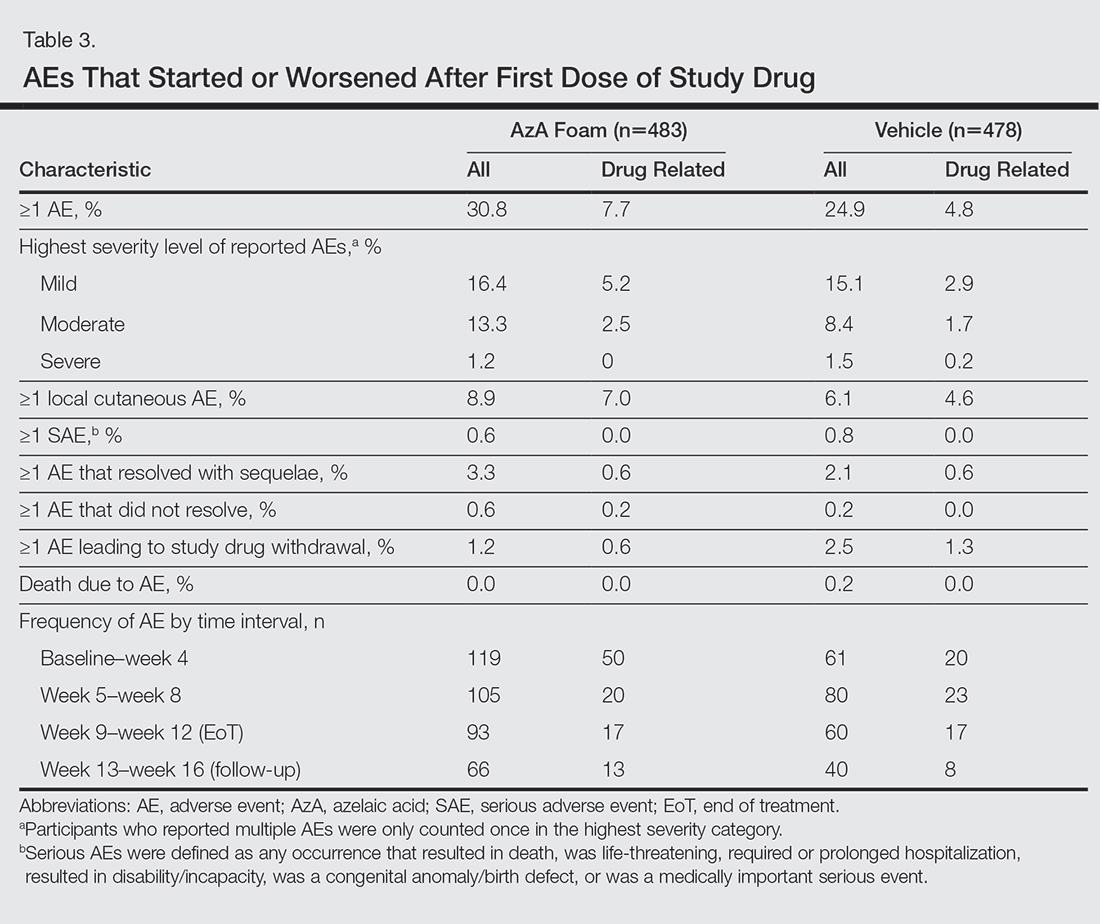

The incidence of drug-related AEs was greater in the AzA group than the vehicle group (7.7% vs 4.8%)(Table 3). Drug-related AEs occurring in at least 1% of the AzA group were pain at application site (eg, tenderness, stinging, burning)(AzA group, 3.5%; vehicle group, 1.3%), application-site pruritus (1.4% vs 0.4%), and application-site dryness (1.0% vs 0.6%). A single drug-related AE of severe intensity (ie, application-site dermatitis) was observed in the vehicle group; all other drug-related AEs were mild or moderate. The incidence of withdrawals due to AEs was lower in the AzA group than the vehicle group (1.2% vs 2.5%). This AE profile correlated with a treatment compliance (the percentage of expected doses that were actually administered) of 97.0% in the AzA group and 95.9% in the vehicle group. One participant in the vehicle group died due to head trauma unrelated to administration of the study drug.

Comment

The results of this study further support the efficacy of AzA foam for the treatment of PPR. The percentage reduction in ILC was consistent with nominal decreases in ILC, a coprimary efficacy end point of this study.12 Almost two-thirds of participants treated with AzA foam achieved a therapeutic response, indicating that many participants who did not strictly achieve the primary outcome of therapeutic success nevertheless attained notable reductions in disease severity. The number of participants who showed any improvement on the IGA scale increased throughout the course of treatment (63.8% AzA foam vs 55.0% vehicle at week 8) up to EoT (71.2% vs 58.8%)(Figure 5). In addition, the number of participants showing any improvement at week 8 (63.8% AzA foam vs 55.0% vehicle)(Figure 5) was comparable to the number of participants achieving therapeutic response at week 12/EoT (66.3% vs 54.4%)(Figure 4). These data suggest that increasing time of treatment increases the likelihood of achieving better results.

Erythema also appeared to respond to AzA foam, with 10.2% more participants in the AzA group demonstrating improvement at week 12/EoT compared to vehicle. The difference in grouped change in erythema rating also was statistically significant and favored AzA foam, sustained up to 4 weeks after EoT.

The outcomes for percentage change in ILC, therapeutic response rate, and grouped change in erythema rating consequently led to the rejection of all 3 null hypotheses in hierarchical confirmatory analyses, underscoring the benefits of AzA foam treatment.

The therapeutic effects of AzA foam were apparent at the first postbaseline evaluation and persisted throughout treatment. Differences favoring AzA foam were observed at every on-treatment evaluation for grouped change in erythema rating, percentage change in ILC, therapeutic response rate, and grouped change in IGA score. Symptoms showed minimal resurgence after treatment cessation, and there were no signs of disease flare-up within the 4 weeks of observational follow-up. In addition, the percentage reduction in ILC remained higher in the AzA foam group during follow-up.

These results also show that AzA foam was well tolerated with a low incidence of discontinuation because of drug-related AEs. No serious drug-related AEs were reported for this study or in the preceding phase 2 trial.12,13 Although not directly evaluated, the low incidence of cutaneous AEs suggests that AzA foam may be better tolerated than prior formulations of AzA14,15 and correlates with high compliance observed during the study.12 Azelaic acid foam appeared to have minimal to no effect on skin color, with more than 88% of participants reporting barely visible or no skin lightening.

Interestingly, the vehicle foam showed appreciable efficacy independent of AzA. Improvements in erythema were recorded in approximately half of the vehicle group at week 12/EoT. A similar proportion attained a therapeutic response, and ILC was reduced by 50.8% at week 12/EoT. Comparable results also were evident in the vehicle group for the primary end points of this study.12 Vehicles in dermatologic trials frequently exert effects on diseased skin16,17 via a skin care regimen effect (eg, moisturization and other vehicle-related effects that may improve skin barrier integrity and function) and thus should not be regarded as placebo controls. The mechanism underlying this efficacy may be due to the impact of vehicle composition on skin barrier integrity and transepidermal water loss.18 The hydrophilic emulsion or other constituents of AzA foam (eg, fatty alcohols) may play a role.

A notable strength of our study is detailed clinical characterization using carefully chosen parameters and preplanned analyses that complement the primary end points. As the latter are often driven by regulatory requirements, opportunities to characterize other outcomes of interest to clinicians may be missed. The additional analyses reported here hopefully will aid dermatologists in both assessing the role of AzA foam in the treatment armamentarium for PPR and counseling patients.

Because participants with lighter skin pigmentation dominated our study population, the impact of AzA foam among patients with darker skin complexions is unknown. Although AzA is unlikely to cause hypopigmentation in normal undiseased skin, patients should be monitored for early signs of hypopigmentation.19,20 Our data also do not allow assessment of the differential effect, if any, of AzA foam on erythema of different etiologies in PPR, as corresponding information was not collected in the trial.