Mycetoma is a subcutaneous disease that can be caused by aerobic bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumycetoma). Diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations, including swelling and deformity of affected areas, as well as the presence of granulation tissue, scars, abscesses, sinus tracts, and a purulent exudate that contains the microorganisms.

The worldwide proportion of mycetomas is 60% actinomycetomas and 40% eumycetomas.1 The disease is endemic in tropical, subtropical, and temperate regions, predominating between latitudes 30°N and 15°S. Most cases occur in Africa, especially Sudan, Mauritania, and Senegal; India; Yemen; and Pakistan. In the Americas, the countries with the most reported cases are Mexico and Venezuela.1

Although mycetoma is rare in developed countries, migration of patients from endemic areas makes knowledge of this condition crucial for dermatologists worldwide. We present a review of the current concepts in the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of actinomycetoma.

Epidemiology

Actinomycetoma is more common in Latin America, with Mexico having the highest incidence. At last count, there were 2631 cases reported in Mexico.2 The majority of cases of mycetoma in Mexico are actinomycetoma (98%), including Nocardia (86%) and Actinomadura madurae (10%). Eumycetoma is rare in Mexico, constituting only 2% of cases.2 Worldwide, men are affected more commonly than women, which is thought to be related to a higher occupational risk during agricultural labor.

Clinical Features

Mycetoma can affect the skin, subcutaneous tissue, bones, and occasionally the internal organs. It is characterized by swelling, deformation of the affected area, and fistulae that drain serosanguineous or purulent exudates.

In Mexico, 60% of cases of mycetoma affect the lower extremities; the feet are the most commonly affected area, followed by the trunk (back and chest), arms, forearms, legs, knees, and thighs.1 Other sites include the hands, shoulders, and abdominal wall. The head and neck area are seldom affected.3 Mycetoma lesions grow and disseminate locally. Bone lesions are possible depending on the osteophilic affinity of the etiological agent and on the interactions between the fungus and the host’s immune system. In severe advanced cases of mycetoma, the lesions may involve tendons and nerves. Dissemination via blood or lymphatics is extremely rare.4

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of actinomycetoma is suspected based on clinical features and confirmed by direct examination of exudates with Lugol iodine or saline solution. On direct microscopy, actinomycetes are recognized by the production of filaments with a width of 0.5 to 1 μm. On hematoxylin and eosin stain, the small grains of Nocardia appear eosinophilic with a blue center and pink filaments. On Gram stain, actinomycetoma grains show positive branching filaments. Culture of grains recovered from aspirated material or biopsy specimens provides specific etiologic diagnosis. Cultures should be held for at least 4 weeks. Additionally, there are some enzymatic, molecular, and serologic tests available for diagnosis.5-7 Serologic diagnosis is available in a few centers in Mexico and can be helpful in some cases for diagnosis or follow-up during treatment. Antibodies can be determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Western blot analysis, immunodiffusion, or counterimmunoelectrophoresis.8

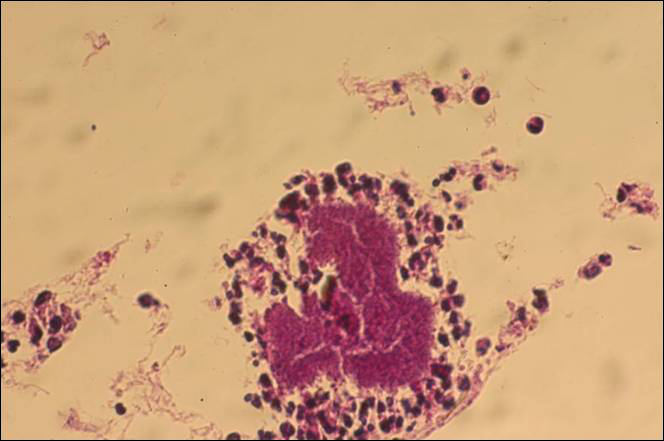

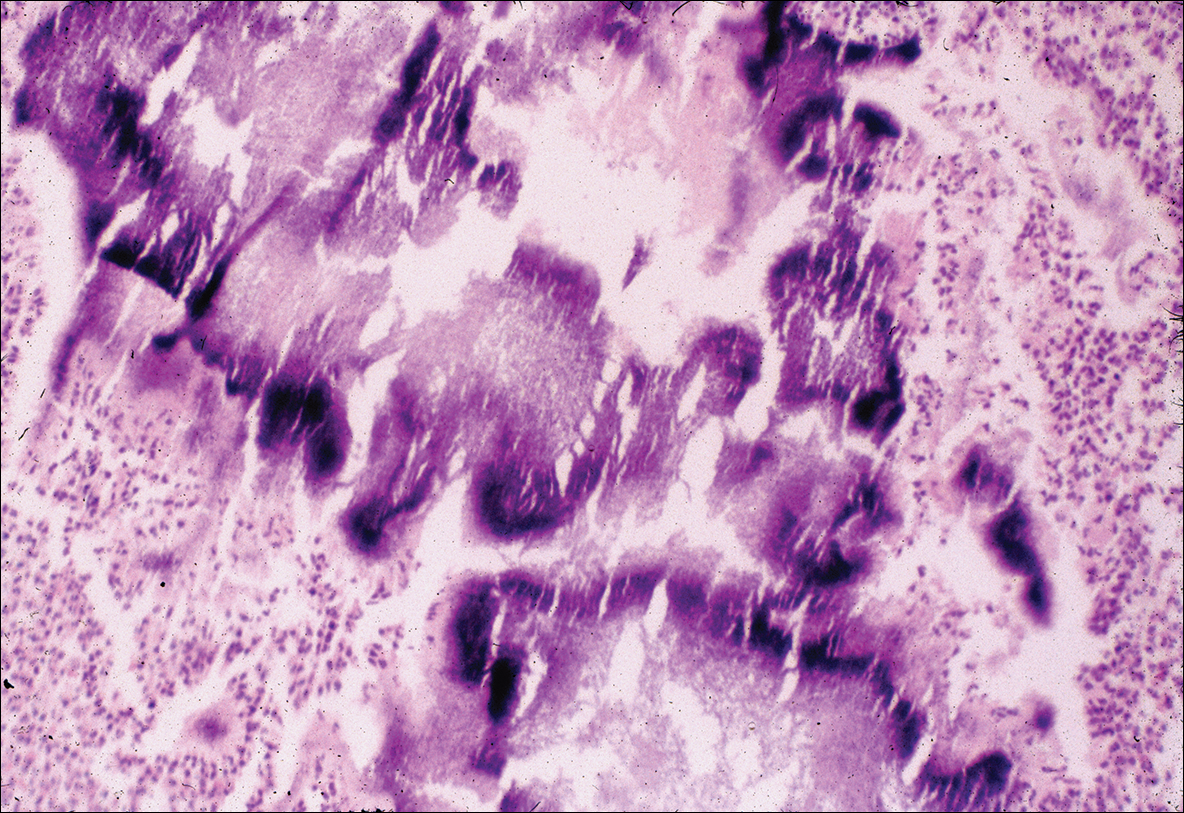

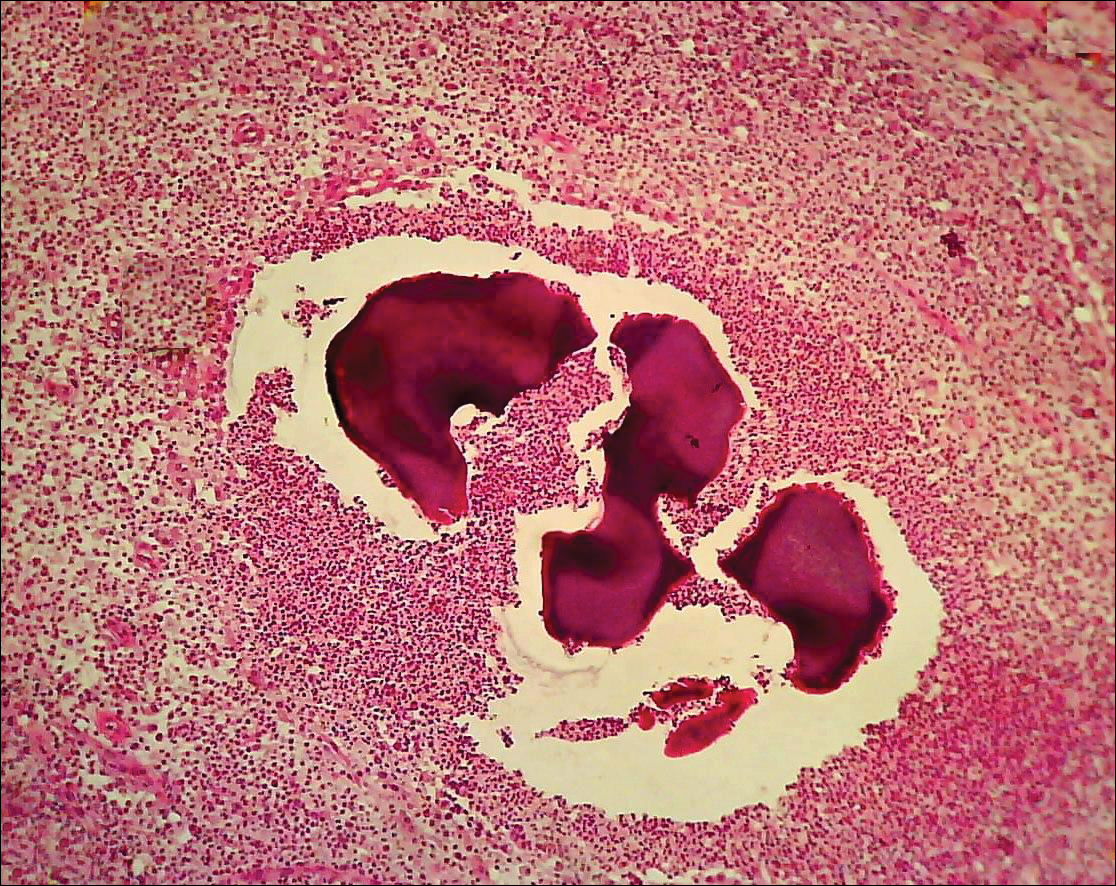

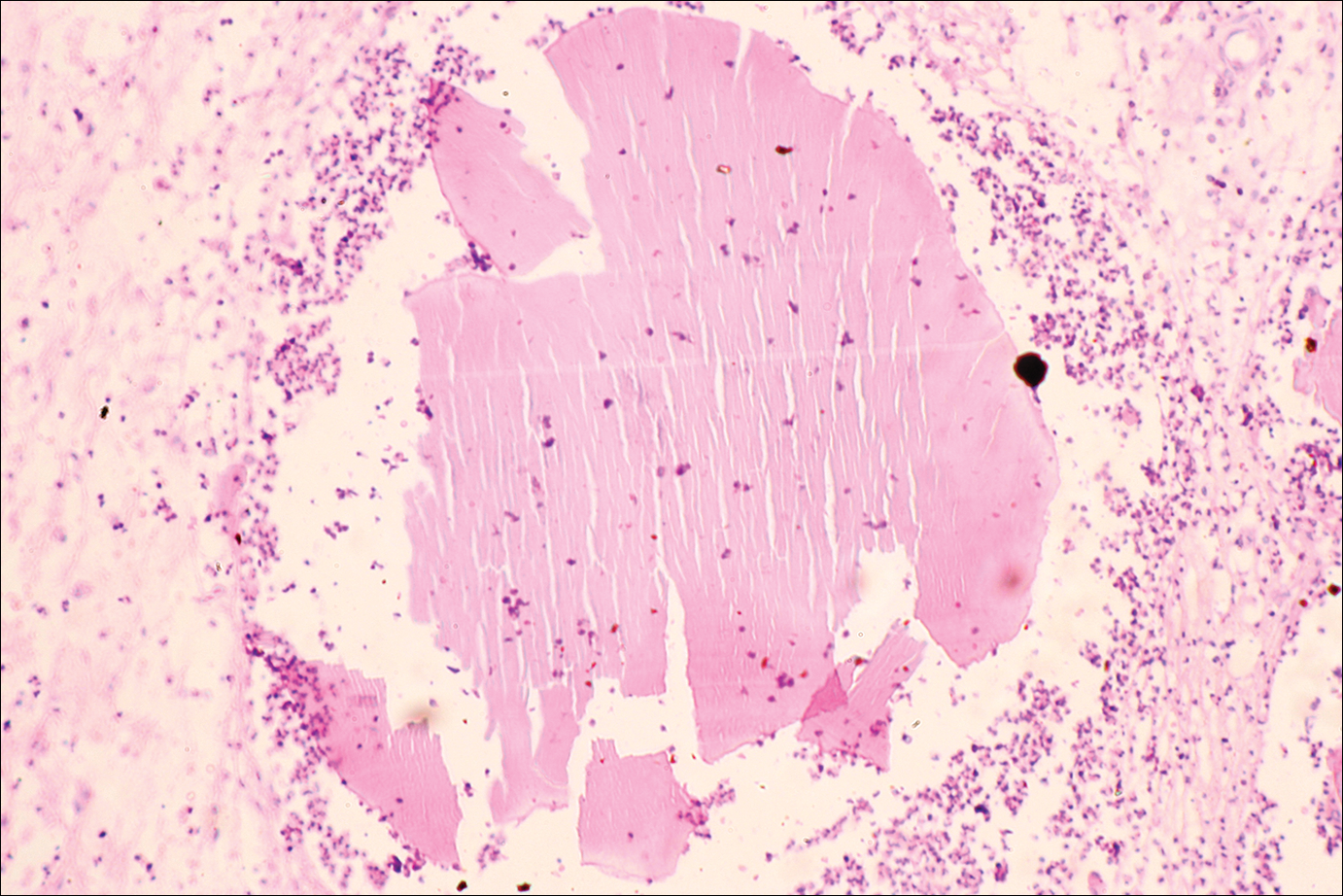

The causative agents of actinomycetoma can be isolated in Sabouraud dextrose agar. Deep wedge biopsies (or puncture aspiration) are useful in observing the diagnostic grains, which can be identified adequately with Gram stain. Grains usually are surrounded and/or infiltrated by neutrophils. The size, form, and color of grains can identify the causative agent.1 The granules of Nocardia are small (80–130 mm) and reniform or wormlike, with club structures in their periphery (Figure 1). Actinomadura madurae is characterized by large, white-yellow granules that can be seen with the naked eye (1–3 mm). On microscopic examination with hematoxylin and eosin stain, these grains are purple and exhibit peripheral pink pseudofilaments (Figure 2).2 The grains of Actinomadura pelletieri are large (1–3 mm) and red or violaceous. They fragment or break easily, giving the appearance of a broken dish (Figure 3). Streptomyces somaliensis forms round grains approximately 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter. These grains stain poorly and are extremely hard. Cutting the grains during processing results in striation, giving them the appearance of a potato chip (Figure 4).2