Cosmetic Corner

Dr. Rich is from Oregon Dermatology and Research, Portland. Dr. Vlahovic is from Temple University School of Podiatric Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr. Joseph is from Roxborough Memorial Hospital, Philadelphia. Dr. Zane was from Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Palo Alto, California. Drs. Hall and Gellings Lowe are from Medical Affairs, Sandoz, a Novartis division, Princeton, New Jersey. Dr. Adigun is from Pinehurst Skin Center, North Carolina.

Dr. Rich has received research grants as a principal investigator from Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Moberg Pharma North America LLC; Sandoz, a Novartis division; Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc; and Viamet Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Dr. Vlahovic is a consultant and speaker for PharmaDerm. Dr. Joseph is a speaker for PharmaDerm and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. Dr. Zane was an employee and shareholder for Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Drs. Hall and Gellings Lowe are employees of Sandoz, a Novartis division. Dr. Adigun is an advisory board member for Sandoz, a Novartis division.

Correspondence: Steve B. Hall, PharmD, 100 College Rd West, Princeton, NJ 08540 (steve.hall@sandoz.com).

The phase 3 clinical trials used to investigate the safety and efficacy of tavaborole,5 efinaconazole,7 and ciclopirox8 were similar in their overall design. All trials were randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled studies in patients with DSO. Each agent was assessed using a once-daily application for a treatment period of 48 weeks.

Primary differences among study designs included the age range of participants, the range of mycotic nail involvement, the presence/absence of tinea pedis, and the nail trimming/debridement protocols used. Differences were observed in the patient eligibility criteria of these trials. Both mycotic area and participant age range were inconsistent for each agent (eTable). Participants with larger mycotic areas usually have a poorer prognosis, as they tend to have a greater fungal load.9 A baseline mycotic area of 20% to 60%,5 20% to 50%,7 and 20% to 65%8 at baseline was required for the tavaborole, efinaconazole, and ciclopirox trials, respectively. Variations in mycotic area between trials can affect treatment efficacy, as clinical cures can be reached quicker by patients with smaller areas of infection. Of note, the average mycotic area of involvement was not reported in the tavaborole studies but was 36% and 40% for the efinaconazole and ciclopirox studies, respectively.5,8 It also is more difficult to achieve complete cure in older patients, as they have poor circulation and reduced nail growth rates.1,10 The participant age range was 18 to 88 years in the tavaborole trials, with 8% of the participants older than 70 years,5 compared to 18 to 71 years in both the efinaconazole and ciclopirox trials.7,8 The average age of participants in each study was approximately 54, 51, and 50 years for tavaborole, efinaconazole, and ciclopirox, respectively. Because factors impacting treatment failure can increase with age, efficacy results can be confounded by differing age distributions across different studies.

Another important feature that differed between the clinical trials was the approach to nail trimming—defined as shortening of the free edge of the nail distal to the hyponychium—which varies from debridement in that the nail plate is removed or reduced in thickness proximal to the hyponychium. In the tavaborole trials, trimming was controlled to within 1 mm of the free edge of the nail,5 whereas the protocol used for the ciclopirox trials allowed nail trimming as necessary as well as moderate debridement before treatment application and on a monthly basis.8 Debridement is an important component in all ciclopirox trials, as it is used to reduce fungal load.11 No trimming control was provided during the efinaconazole trials; however, debridement was prohibited.7 These differences can dramatically affect the study results, as residual fungal elements and portions of infected nails are removed during the trimming process in an uncontrolled manner, which can affect mycologic testing results as well as the clinical efficacy results determined through investigator evaluation. Discrepancies regarding nail trimming approach inevitably makes the trial results difficult to compare, as mycologic cure is not translatable between studies.

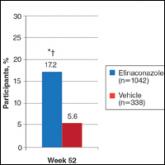

Furthermore, somewhat unusually, complete cure rate variations were observed between different study centers in the efinaconazole trials. Japanese centers in the first efinaconazole study (NCT01008033) had higher complete cure rates in both the efinaconazole and vehicle treatment arms, which is notable because approximately 29% of participants in this study were Asian, mostly hailing from 33 Japanese centers. The reason for these confounding results is unknown and requires further analysis.

Lastly, the presence or absence of tinea pedis can affect the response to onychomycosis treatment. In the tavaborole trials, patients with active interdigital tinea pedis or exclusively plantar tinea pedis or chronic moccasin-type tinea pedis requiring treatment were excluded from the studies.5 In contrast, only patients with severe moccasin-type tinea pedis were excluded in efinaconazole trials.7 The ciclopirox studies had no exclusions based on presence of tinea pedis.8 These differences are noteworthy, as tinea pedis can serve as a reservoir for fungal infection if not treated and can lead to recurrence of onychomycosis.12

In recent years, disappointing efficacy has resulted in the failure of several topical agents for onychomycosis during their development; however, there are several aspects to consider when examining efficacy data in onychomycosis studies. Obtaining a complete cure in onychomycosis is difficult. Because patients applying treatments at home are unlikely to undergo mycologic testing to confirm complete cure, visual inspections are helpful to determine treatment efficacy.

Despite similar overall designs, notable differences in the study designs of the phase 3 clinical trials investigating tavaborole, efinaconazole, and ciclopirox are likely to have had an effect on the reported results, making the efficacy of the agents difficult to compare. It is particularly tempting to compare the primary end point results of each trial, especially considering tavaborole and efinaconazole had primary end points with the same parameters; however, there are several other factors (eg, age range of study population, extent of infection, nail trimming, patient demographics) that may have affected the outcomes of the studies and precluded a direct comparison of any end points. Without head-to-head investigations, there is room for prescribing clinicians to interpret results differently.

Writing and editorial assistance was provided by ApotheCom Associates, LLC, Yardley, Pennsylvania, and was supported by Sandoz, a Novartis division.

Onychomycosis is a common progressive fungal infection of the nail bed, matrix, or plate leading to destruction and deformity of the toenails and...

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nail unit that may lead to dystrophy and disfigurement over time. It accounts for up to 50% of all nail...