Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, rapidly growing, aggressive neoplasm with a generally poor prognosis. The cells of origin are highly anaplastic and share structural and immunohistochemical features with various neuroectodermally derived cells. Although Merkel cells, which are slow-acting cutaneous mechanoreceptors located in the basal layer of the epidermis, and MCC share immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features, there is limited evidence of a direct histogenetic relationship between the two.1,2 Additionally, some extracutaneous neuroendocrine tumors have features similar to MCC; therefore, although it may be more accurate and perhaps more practical to describe these lesions as primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin, the term MCC is more commonly used both in the literature and in clinical practice.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma typically presents in the head and neck region in white patients older than 70 years of age and in the immunocompromised population.3-6 The mean age of diagnosis is 76 years for women and 74 years for men.7 The incidence of MCC in the United States tripled over a 15-year period, and there are approximately 1500 new cases of MCC diagnosed each year, making it about 40 times less common than melanoma.8 The 5-year survival rate for patients without lymph node involvement is 75%, whereas the 5-year survival rate for patients with distant metastases is 25%.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is thought to develop through 1 of 2 distinct pathways. In a virally mediated pathway, which represents at least 80% of cases, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) monoclonally integrates into the host genome and promotes oncogenesis via altered p53 and retinoblastoma protein expression.10-12 The remainder of cases are believed to develop via a nonvirally mediated pathway in which genetic anomalies, immune status, and environmental factors influence oncogenesis.10-13

Due to the similarity between MCC and metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially small-cell lung carcinomas, immunohistochemistry is important in making the diagnosis. Cytokeratin 20 and neuron-specific enolase positivity and thyroid transcription factor 1 negativity are the most useful markers in identifying MCC.

Regression of MCC is a very rare and poorly understood event. A 2010 review of the literature described 22 cases of spontaneous regression.14 We report a rare case of rapid and complete regression of MCC following punch biopsy in a 96-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 96-year-old woman presented with a rapidly enlarging lesion overlying the suprasternal notch of 8 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The lesion consisted of a 5.0×4.5-cm, friable, erythematous, flesh-colored nodule with ulceration and heavy crusting. Surrounding the nodule was an erythematous to violaceous patch extending to the anterior chest and bilateral supraclavicular area. No cervical or clavicular lymphadenopathy was observed. According to the patient’s caregiver, the lesion originated as a small, erythematous, scaly macule that rapidly increased in size over an 8-week period to a maximum of 5.0×4.5 cm at presentation. The lesion bled on 2 or 3 occasions during the 8-week period and was controlled with a warm compress. The patient’s caregiver had treated the lesion with topical tea tree oil (for malodor) and antibiotic ointment as needed. The clinical differential diagnosis included squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, amelanotic melanoma, cutaneous metastasis of a primary visceral malignancy, basal cell carcinoma, and MCC. Biopsy of the lesion was recommended at this time but the patient’s family declined.

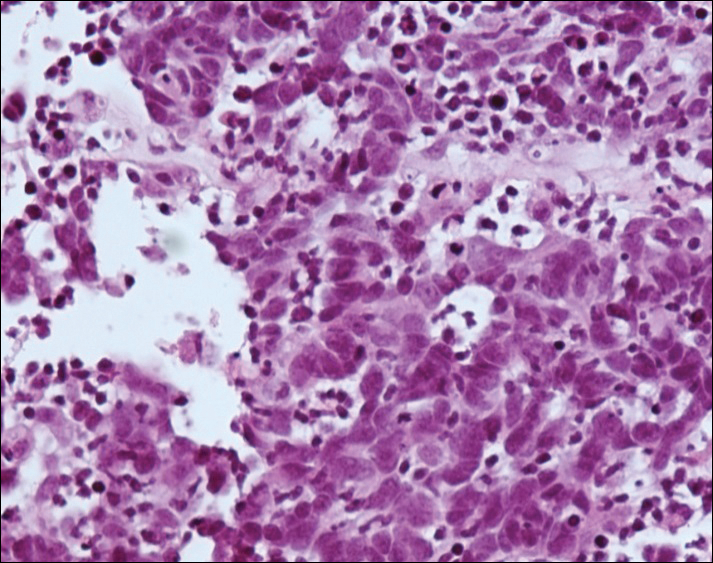

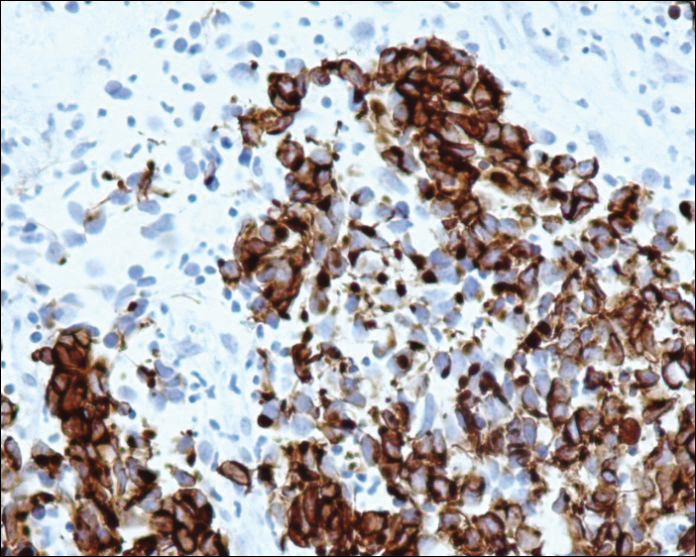

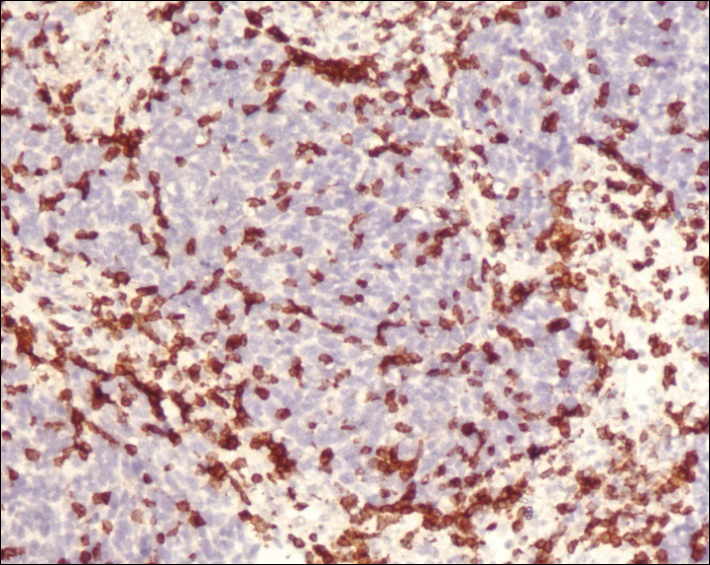

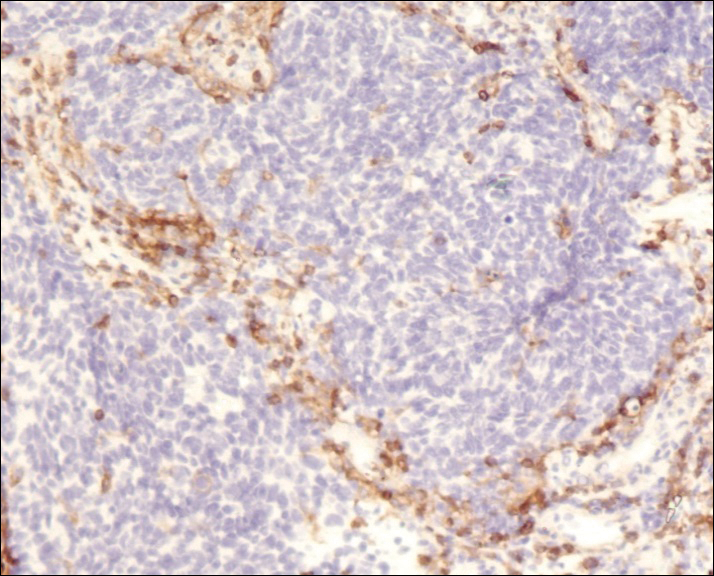

A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at a follow-up visit 4 weeks later (12 weeks after the reported onset of the lesion). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a small-cell neoplasm with stippled nuclei and scant cytoplasm forming a nested and somewhat trabecular pattern. Mitotic activity, apoptosis, and nuclear molding also were present (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 20 with a dotlike, paranuclear pattern (Figure 3). Staining for CAM 5.2 also was positive. Cytokeratin 5/6, human melanoma black 45, and leukocyte common antigen were negative. The immunophenotyping of the lymphocytic response to the tumor showed that the majority of intratumoral lymphocytes were CD8 positive (Figure 4). CD4-positive lymphocytes were predominantly seen at the periphery of the tumor nests without tumor infiltration (Figure 5). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of MCC was made. The patient’s family declined treatment based on her advanced age and current health status, which included advanced dementia.

Two weeks after the punch biopsy, the lesion had noticeably decreased in size and lost its dome-shaped appearance. Within 8 weeks after biopsy (20 weeks since the lesion first appeared), the lesion had completely resolved (Figure 6). The patient was lost to follow-up months later, but no recurrence of the lesion was reported.