The Ixodes tick is prevalent in temperate climates worldwide. During a blood meal, pathogens may be transmitted from the tick to its host. Borrelia burgdorferi, a spirochete responsible for Lyme disease, is the most prevalent pathogen transmitted by Ixodes ticks.1 Borrelia mayonii recently was identified as an additional cause of Lyme disease in the United States.2

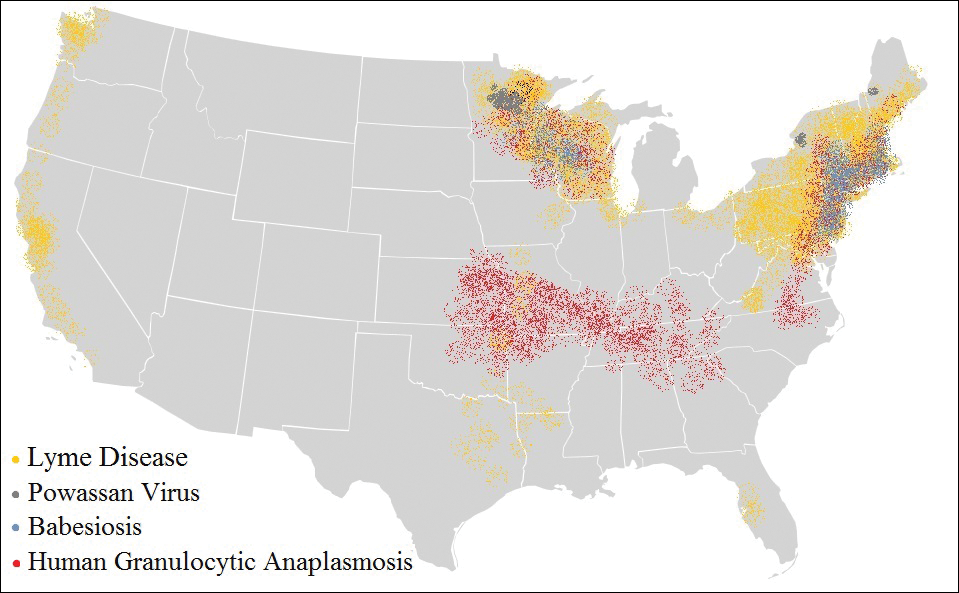

The Ixodes tick also is associated with several less common pathogens, including Babesia microti and the tick-borne encephalitis virus, which have been recognized as Ixodes-associated pathogens for many years.3,4 Other pathogens have been identified, including Anaplasma phagocytophilum, recognized in the 1990s as the cause of human granulocytic anaplasmosis, as well as the Powassan virus and Borrelia miyamotoi.5-7 Additionally, tick paralysis has been associated with toxins in the saliva of various species of several genera of ticks, including some Ixodes species.8 Due to an overlap in geographic distribution (Figure) and disease presentations (eTable), it is important that physicians be familiar with these regional pathogens transmitted by Ixodes ticks.

Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis

Formerly known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, human granulocytic anaplasmosis is caused by A phagocytophilum and is transmitted by Ixodes scapularis, Ixodes pacificus, and Ixodes persulcatus. The incidence of human granulocytic anaplasmosis in the United States increased 12-fold from 2001 to 2011.9

Presenting symptoms generally are nonspecific, including fever, night sweats, headache, myalgias, and arthralgias, often resulting in misdiagnosis as a viral infection. Laboratory abnormalities include mild transaminitis, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia.9,10 Although most infections resolve spontaneously, 3% of patients develop serious complications. The mortality rate is 0.6%.11

A diagnosis of human granulocytic anaplasmosis should be suspected in patients with a viral-like illness and exposure to ticks in an endemic area. The diagnosis can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), acute- and convalescent-phase serologic testing, or direct fluorescent antibody screening. Characteristic morulae may be present in granulocytes.12 Treatment typically includes doxycycline, which also covers B burgdorferi coinfection. When a diagnosis of human granulocytic anaplasmosis is suspected, treatment should never be delayed to await laboratory confirmation. If no clinical improvement is seen within 48 hours, alternate diagnoses or coinfection with B microti should be considered.10

Babesiosis

The protozoan B microti causes babesiosis in the United States, with Babesia divergens being more common in Europe.13 Reported cases of babesiosis in New York increased as much as 20-fold from 2001 to 2008.14 Transmission primarily is from the Ixodes tick but rarely can occur from blood transfusion.15 Tick attachment for at least 36 hours is required for transmission.13

The clinical presentation of babesiosis ranges from asymptomatic to fatal. Symptoms generally are nonspecific, resembling a viral infection and including headache, nausea, diarrhea, arthralgia, and myalgia. Laboratory evaluation may reveal hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, transaminitis, and elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels.16 Rash is not typical. Resolution of symptoms generally occurs within 2 weeks of presentation, although anemia may persist for months.13 Severe disease is more common among elderly and immunocompromised patients. Complications include respiratory failure, renal failure, congestive heart failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. The mortality rate in the United States is approximately 10%.10,16

A diagnosis of babesiosis is made based on the presence of flulike symptoms, laboratory results, and history of recent travel to an endemic area. A thin blood smear allows identification of the organism in erythrocytes as ring forms or tetrads (a “Maltese cross” appearance).17 Polymerase chain reaction is more sensitive than a blood smear, especially in early disease.18 Indirect fluorescent antibody testing is species-specific but cannot verify active infection.10

Treatment of babesiosis is indicated for symptomatic patients with active infection. Positive serology alone is not an indication for treatment. Asymptomatic patients with positive serology should have diagnostic testing repeated in 3 months with subsequent treatment if parasitemia persists. Mild disease is treated with atovaquone plus azithromycin or clindamycin plus quinine. Severe babesiosis is treated with quinine and intravenous clindamycin and may require exchange transfusion.10 Coinfection with B burgdorferi should be considered in patients with flulike symptoms and erythema migrans or treatment failure. Coinfection is diagnosed by Lyme serology plus PCR for B microti. This is an important consideration because treatment of babesiosis does not eradicate B burgdorferi infection.19