Rosacea is a chronic skin condition that can be classified into 4 subtypes: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea is characterized by redness of the face and excessive blushing. Papulopustular rosacea is a more severe form of disease that is characterized by papules and pustules of the central face. If left untreated, these subtypes may progress to phymatous rosacea, which is characterized by skin thickening, fibrosis, and cosmetic disfigurement. Ocular rosacea is characterized by redness and irritation of the eyes.1 Rosacea patients often are burdened with embarrassment, social anxiety, and psychiatric comorbidities.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) is a validated and reliable self-administered tool for diagnosis of depression and designation of depression severity. This instrument could prove useful in screening for depression in rosacea patients given the high incidence of psychiatric comorbidities in this patient population.2 The PHQ-9 consists of 9 questions that assess for criteria used to define depressive disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition).3 The questionnaire is brief, easy to administer, and has 88% specificity and sensitivity.4

Other studies have evaluated the relationship between rosacea and psychiatric illness, but the PHQ-9 was not used as a screening tool.7,8 Rosacea patients are at increased risk for having psychiatrist-diagnosed depression.5 In one assessment, a positive correlation between rosacea and psychiatric illness was noted using the Dermatology Life Quality Index, the rejection scale of the Questionnaire on Experience with Skin Complaints, and the German version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.6 Interpretation of Rosacea Quality of Life and Dermatology Life Quality Index scores indicated that rosacea has a negative impact on quality of life.7

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between self-assessed rosacea severity scores and level of depression using the validated rosacea self-assessment tool and the PHQ-9 questionnaire, respectively.

Methods

Study Population

Study participants were adult patients from the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) dermatology clinic from January 2011 to December 2014 who had received a diagnosis of rosacea (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] code 695.3) from a Wake Forest dermatologist. Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to initiation of the study. Data collection occurred from October 2014 through February 2015. A total of 478 patients met criteria for participation in the study and were identified from the Wake Forest Baptist Hospital Transitional Data Warehouse and the electronic medical record. Because rosacea typically is not diagnosed in children and the data measures are not validated in children, this demographic group was excluded from participation.

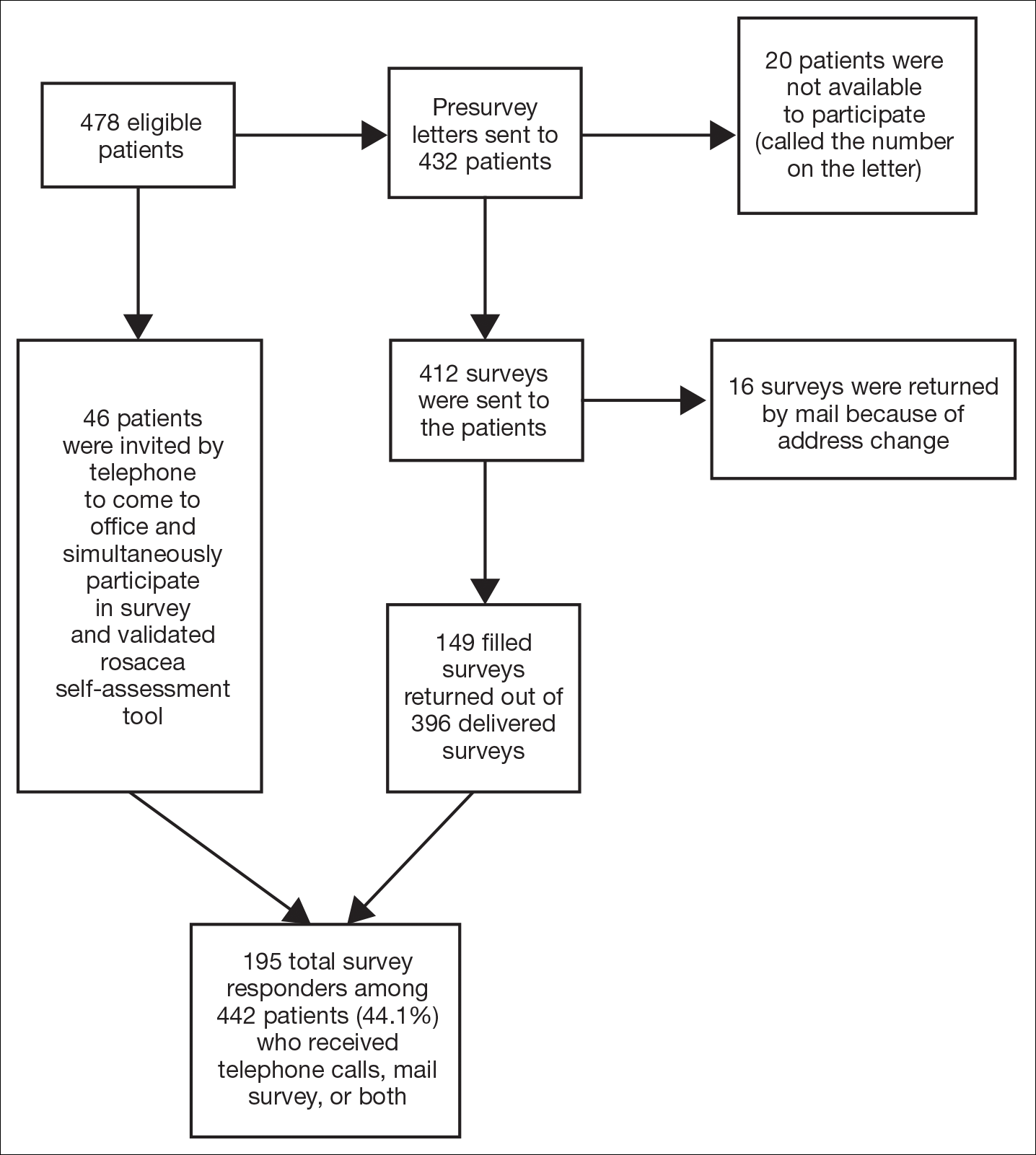

Of 478 eligible patients who were invited to participate via mail or telephone, 46 completed the rosacea self-assessment tool and PHQ-9 survey in person. A total of 432 patients were mailed a presurvey recruitment letter notifying them that they would be receiving a survey in the mail unless they contacted the study team to decline participation. An email address and telephone number for the study team was provided. Twenty patients declined to participate in the study; surveys were then mailed to the remaining 412 patients. Sixteen of the mailed surveys were returned by the post office due to an incorrect address. A total of 195 surveys (149 through mail and 46 in person) were completed and analyzed. All survey respondents completed the validated rosacea self-assessment tool (Figure 1); of them, 183 completed the PHQ-9. Participants in this study received compensation for travel expenses and time.

Self-assessments

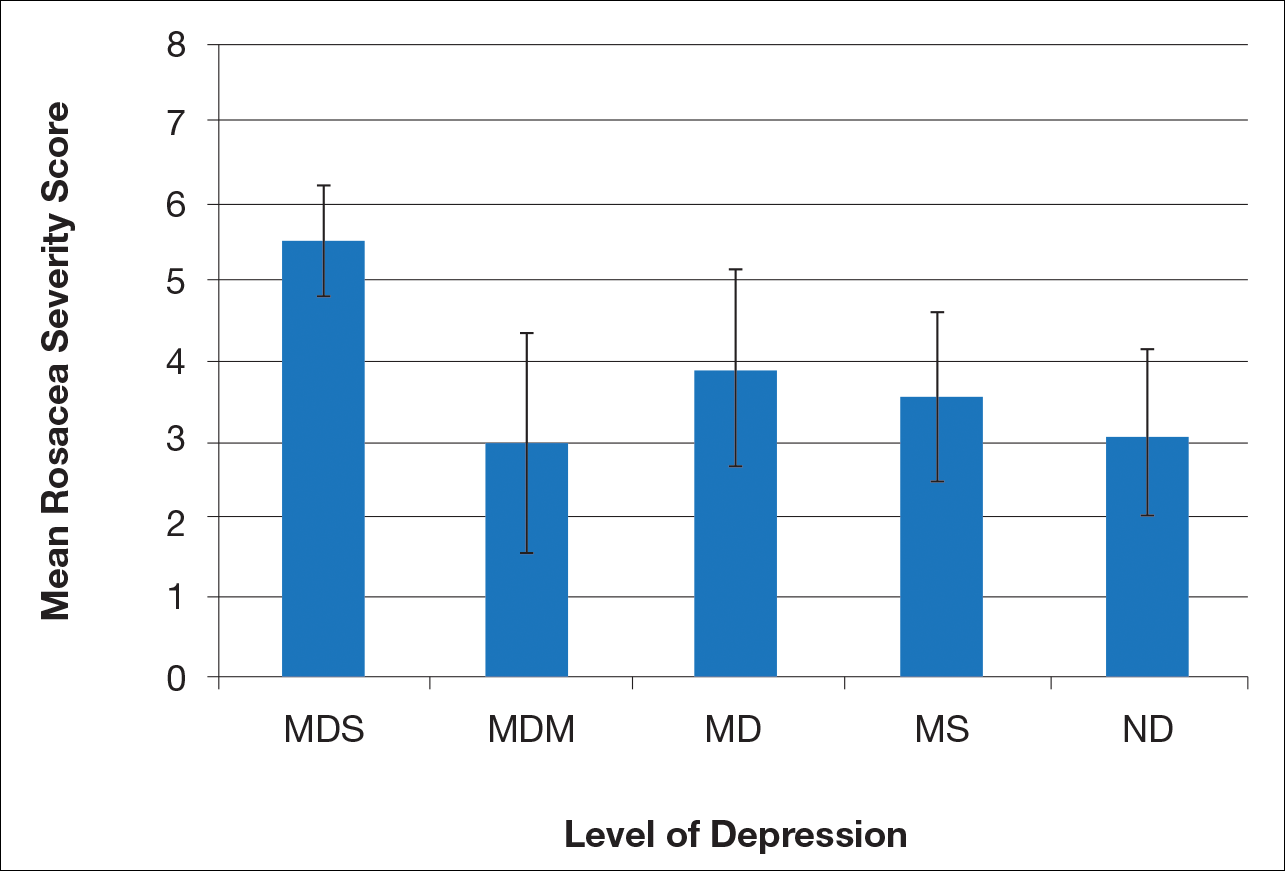

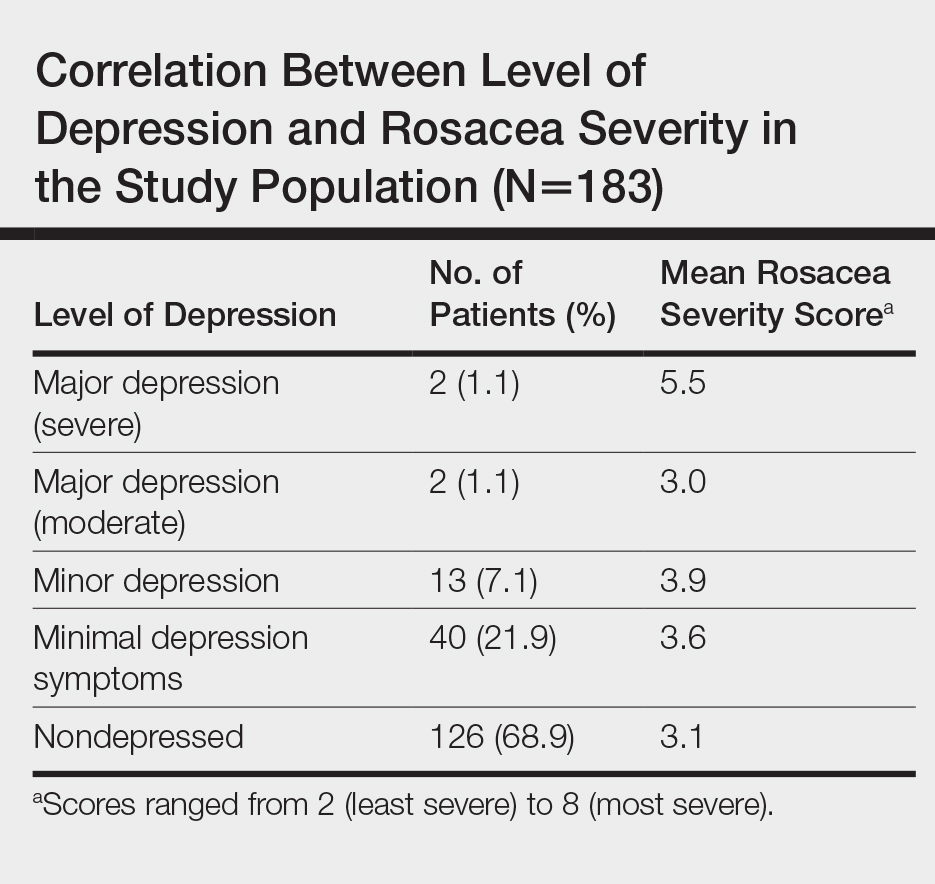

Patients selected images to self-identify the severity of their rosacea symptoms, including erythema, papulopustular lesions, ocular symptoms, and nasal involvement by looking at photographs on the self-assessment tool, which showed various rosacea severity levels. Scores ranged from 2 (least severe) to 8 (most severe). The PHQ-9 survey was completed by participants to assess mental health and mood.

Statistical Analysis

Results were reported using descriptive statistics. Regression analysis was performed to identify independent outcome predictors. To study the relationship between age and demographic variables, the population was divided into 2 groups: patients aged 60 years and older and patients younger than 60 years. Correlation of variables with duration of disease also was studied by creating 2 groups: patients with a disease duration of 11 years or longer and patients with a disease duration of less than 11 years. Comparisons were completed between groups using χ2 tests for proportions and t tests or analysis of variance for continuous variables. Analysis of variance was applied among all patients classified according to the following levels of depression: nondepressed, minimal depression symptoms, minor depression, major depression (moderate), and major depression (severe).

Results

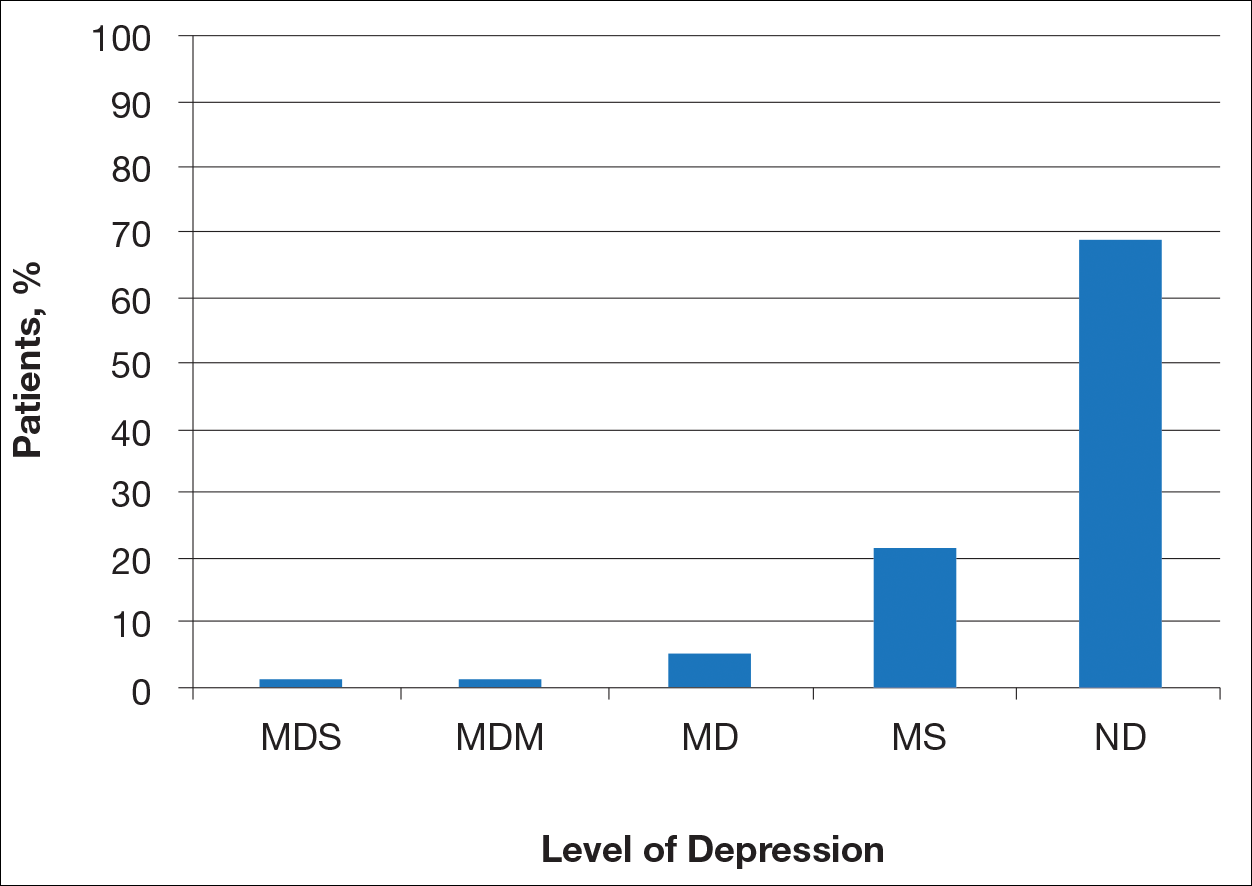

There is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and depression when comparing across the following levels of depression: nondepressed, minimal depression symptoms, minor depression, major depression (moderate), and major depression (severe)(P=.006; F=5.18; N=183)(Figures 2 and 3). There was no statistically significant difference in rosacea severity between the moderate and severe major depression groups.

Most patients reported they were nondepressed (68.9%). As measured by the PHQ-9, 31.1% of patients experienced some level of depression: 21.9% reported minimal depression symptoms, 7.1% reported minor depression, 1.1% reported major depression (moderate), and 1.1% reported major depression (severe)(Table).

Comment

There is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and level of depression. In our study, nearly one-third of patients reported some degree of depression. The reason for this correlation may be due to disease stigmatization and decreased quality of life due to the somatic symptoms of rosacea. Our study reinforced the results of other studies evaluating the psychosocial impact of rosacea.8,9 Depression is associated with poor treatment adherence and poor outcomes in rosacea patients; therefore, depression may serve as an important outcome measure.10 The psychosocial impact of rosacea can be severe, but with disease improvement, there often is an improvement in the patient’s psychosocial status.7

There are several limitations to our study. The study population consisted of patients at a university dermatology clinic who may not be representative of patients in the general population; however, our hospital system does not require referral and provides care to a large percentage of the surrounding community.

Clinical implementation of the validated rosacea self-assessment tool and PHQ-9 may have several benefits. Patient-assessed rosacea severity and psychosocial impact obtained via use of these tools would provide physicians with information to fine-tune rosacea treatment regimens. Patients with the greatest social impact may require a more aggressive treatment approach. Early detection of depression in the rosacea population is important in informing treatment strategy and improving outcomes. Physicians should pay close attention to signs of depression in rosacea patients and determine if psychiatric treatment or referral for psychiatric evaluation is indicated. The correlation between rosacea and depression underscores the importance of treating this highly impactful disease; however, the low number of responders from the major depression (moderate) subgroup prevented us from making any strong conclusion about this specific subgroup.