To the Editor:

A 38-year-old woman was diagnosed with common variable immune deficiency (CVID) by an immunologist at an outside institution 1 year prior to the current presentation. The diagnosis was based on history of severe recurrent sinopulmonary tract, inner ear, Clostridium difficile, urinary tract, and herpes zoster infections of approximately 6 years’ duration, as well as persistently low IgG, IgA, and IgM levels of 530 mg/dL (reference range, 690–1400 mg/dL), 29 mg/dL (reference range, 88–410 mg/dL), and 30 mg/dL (reference range, 34–210 mg/dL), respectively, with failure to respond to vaccinations (ie, Haemophilus influenzae type B, Streptococcus pneumoniae, diphtheria IgG antibody, tetanus antibody). She was started on replacement intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 40 g monthly (400 mg/kg) for CVID. She had a family history of CVID diagnosed in her son and sister.

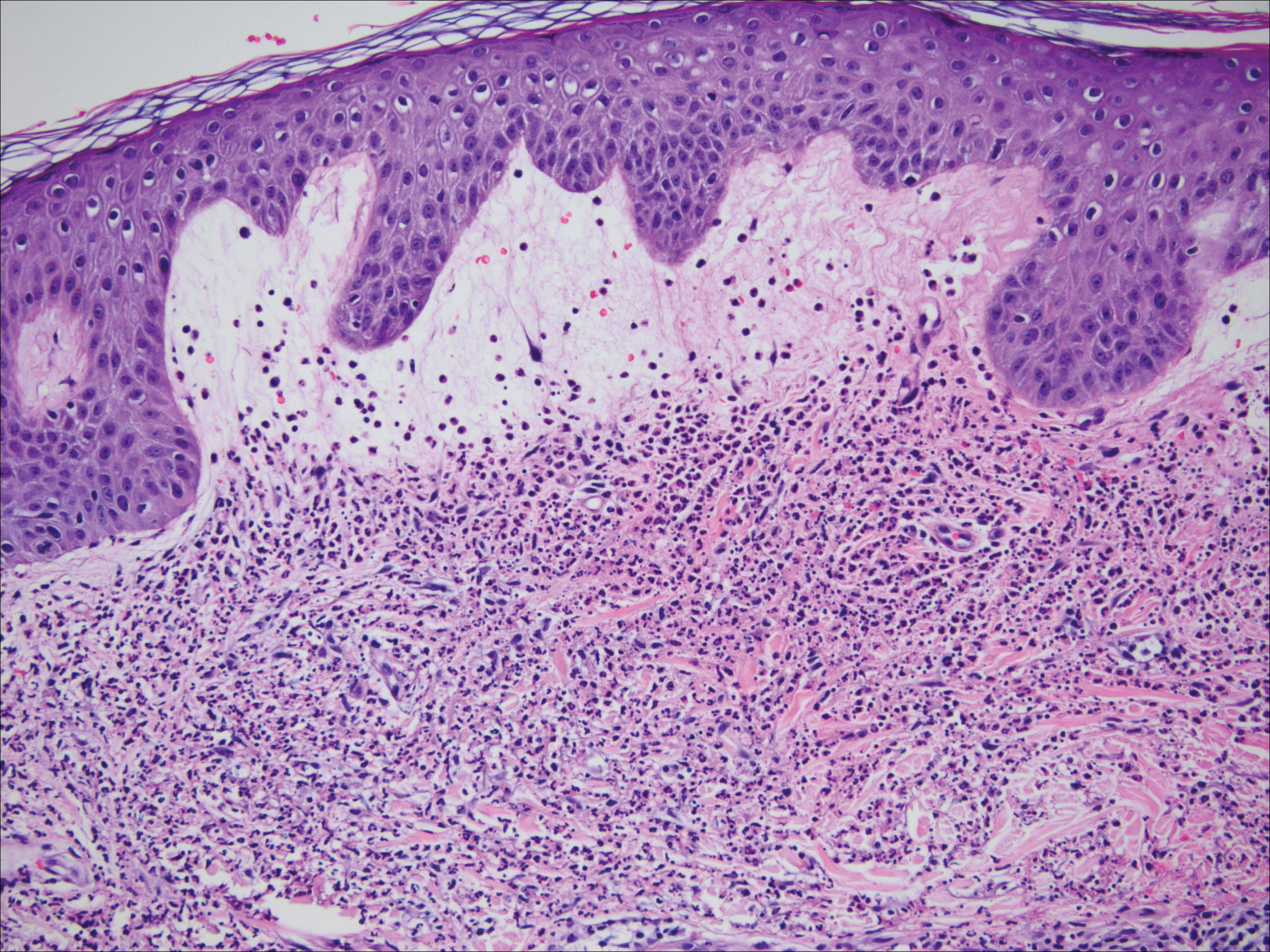

One year after the CVID diagnosis, she was diagnosed with Sweet syndrome (SS) by a physician at our institution via biopsy of a lesion on the left arm (Figure 1) that showed dense dermal infiltrate of neutrophils with scattered background apoptotic nuclear debris without evidence of vasculitis (Figure 2). Gram stain and microbial biopsy cultures were negative for mycobacterial, fungal, and bacterial organisms. Cutaneous lesions failed to respond to courses of intravenous antibiotics. Sarcoidosis workup was unremarkable and was pursued to exclude the association with SS. Other negative testing included antinuclear antibody, human immunodeficiency virus, rheumatoid factor, thyroid-stimulating hormone, Ro and La autoantibodies, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antimitochondrial antibody, and urinalysis. Occult malignancy was excluded with negative bone marrow biopsy; cerebrospinal fluid analysis; esophagogastroduodenoscopy; colonoscopy; and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis.

Figure 2. Dense, bandlike, interstitial, and perivascular dermal infiltrate of mature neutrophils involving the upper dermis. Background papillary dermal edema with mild associated epidermal spongiosis and abundant karyorrhectic debris (leukocytoclasis) with a few admixed lymphocytes and occasional eosinophils. Reactive endothelial changes also were present, but frank vascular fibrinoid necrosis (vasculitis) was absent (H&E, original magnification ×40).

Sweet syndrome flares in this patient began with a prodromal syndrome of fever, chills, fatigue, diarrhea, and severe local neuropathic pain. Cutaneous lesions erupted 2 days later, most frequently on the arms and fingers. Preemptive treatment with prednisone 30 to 40 mg when the prodrome was present did not arrest cutaneous lesion development. Flares initially occurred every 3 to 5 weeks.

She initially was successfully treated with high-dose prednisone 100 mg daily during SS flares. Prolonged low-dose prednisone maintenance (10–20 mg) and hydroxychloroquine failed to control her frequent exacerbations. Dapsone was intolerable secondary to an adverse reaction. She continued to have frequent exacerbations of the SS requiring hospitalizations.

During SS flares, CVID was stable with infrequent systemic infections. Although a causal relationship between CVID and SS was unclear, an empiric increase in IVIG dose was made by her immunologist to test if it would decrease the frequency of the cutaneous flares. Subsequently, the IVIG dose was increased to 60 g monthly followed by 200 g monthly after approximately 4 months with a partial initial response in the beginning of therapy for the first 6 months. However, episodes resumed with increasing frequency with cutaneous lesion flares every 2 to 3 weeks. In a 3-month period, the patient had at least 4 hospitalizations for SS flares. Finally, 18 months after the diagnosis of SS was made, she was started on metronomic cyclophosphamide at a daily oral dose of 100 mg, later reduced to 50 mg daily after she developed mild neutropenia. She was continued on monthly IVIG replacement at a higher dose of 200 g divided over 2 days for CVID throughout the course of the disease and to the present time. Since then, the frequency of SS flares has notably reduced. She required 1 hospitalization after cyclophosphamide was initiated. She uses short-pulse prednisone (1 mg/kg) for 3 to 5 days when new skin lesions appear in addition to cyclophosphamide.

Common variable immune deficiency, the most common primary immunodeficiency, initially can present in adulthood.1,2 Its hallmarks include low levels of serum immunoglobulin, most notably IgG with most patients having concurrent deficiencies of IgA and IgM, and impaired antibody responses with recurrent or atypical infections. It has been associated with autoimmune diseases, granulomatous disease, and inflammatory disorders.2 Failure to mount protective levels of antibody titer after vaccination demonstrates the deficiency of antibody production.1 Lack of recognition of this clinical spectrum may lead to delayed diagnosis and more importantly stalls the initiation of immunoglobulin replacement therapy.1 The customary dose of immunoglobulin replacement is 400 mg/kg given in a single monthly infusion2; however, doses should be individualized and based on clinical response.1