Case Report

A 7-year-old boy with a history of shellfish anaphylaxis, pollen allergy, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, frequent headaches and ear infections, sinusitis, bronchitis, vitiligo, warts, and cold sores presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread crusting, cracking, red rash that had been present since 6 months of age. The patient’s mother reported that he had many sleepless nights from uncontrolled itching. His medications included albuterol solution for nebulization, loratadine, and montelukast. Prior to the current presentation he had been treated with triamcinolone and betamethasone creams by the pediatrician. Despite compliance with topical therapy, his mother stated the itching persisted and lesions lingered with minimal improvement. He also was treated with oral corticosteroids for episodic sinusitis and bronchitis, which was beneficial to the skin lesions for only a short duration. The patient was adopted and therefore his family history was unavailable.

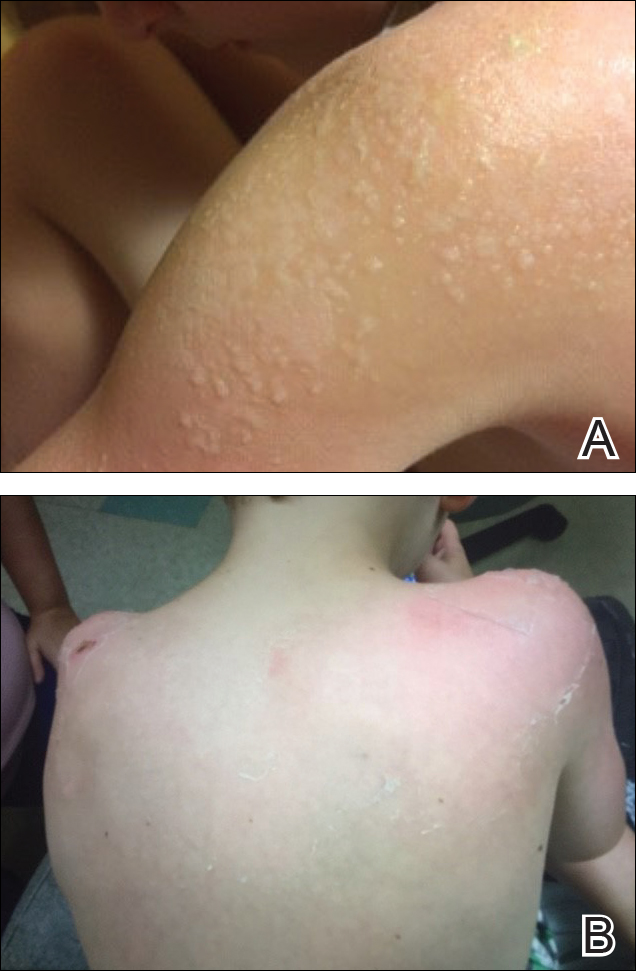

During physical examination, the patient was in the fetal position on the examination table and appeared uncomfortable, scratching himself. The patient admitted to severe widespread itching and burning. On skin examination, multiple thick, lichenified, highly pruritic plaques coalesced on the knees, ankles, arms, and wrists, and very discreet scaly patches were present on the scalp. Annular patches covered 50% of the patient’s body, with highly inflamed lesions concentrated in skin folds (Figure 1), leading to diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Over the course of several months, a number of topical therapies were prescribed. The calcineurin inhibitor pimecrolimus cream 1% proffered minimal relief, and the patient experienced burning with crisaborole despite attempts to combine it with emollients and topical corticosteroids. The patient and his mother favored intermittent use of topical corticosteroids alone; however, he experienced frequent disease flares. Stabilized hypochlorous acid spray and mupirocin 2% antibiotic ointment were included in the treatment regimen as adjunctive topical therapies. Additionally, the patient underwent bleach and vinegar bath therapy without success.

Although UVA and UVB phototherapy has shown to be safe and effective in children, our patient had limited treatment options due to insurance restrictions. The patient had been taking oral corticosteroids on and off for years prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic.

Our patient weighed approximately 40 lb and was prescribed methotrexate 5 mg once weekly for 2 weeks along with oral folic acid 1 mg once daily, except when taking the methotrexate. Laboratory workup was ordered at 2- and then 4-week intervals. After 2 weeks of treatment, methotrexate was increased to 10 mg once weekly. His asthma was carefully monitored by the allergist, and his mother was instructed to stop the medication if he had worsening shortness of breath or exacerbation of asthma symptoms. He tolerated methotrexate at 10 mg once weekly well without clinical side effects for 6 months. His mother observed less frequent ear and sinus infections during methotrexate therapy; however, he developed anemia over time and the methotrexate was discontinued. Understanding the nature of off-label use in administering dupilumab, the patient’s mother consented to a scheduled dosage of 300 mg subcutaneous (SQ) injection every month in the absence of a loading dose with the assumption of future modifications pending his response to therapy.

Five days after treatment with a 300-mg SQ dupilumab injection, the patient returned to clinic for evaluation of a vesicular rash with subsequent peeling confined to the shoulders (Figure 2). He and his mother denied any UV exposure, citing he had been completely out of the sun. He denied constitutional symptoms including fever, malaise, swelling, joint pain, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, enlarged lymph glands, difficulty urinating, breathing, or neurological disturbance. Upon physical examination, the rash was not considered to be a drug eruption. Had a mild drug reaction been suspected, a careful rechallenge, weighing the risks and benefits, would have been considered and was discussed with the mother and patient. New-onset or worsening eye symptoms should be reported; therefore, a referral to ophthalmology was prompted due to our patient’s history of rhinoconjunctivitis and persistent conjunctival injection observed early after initiating dupilumab therapy. Nothing remarkable was found.

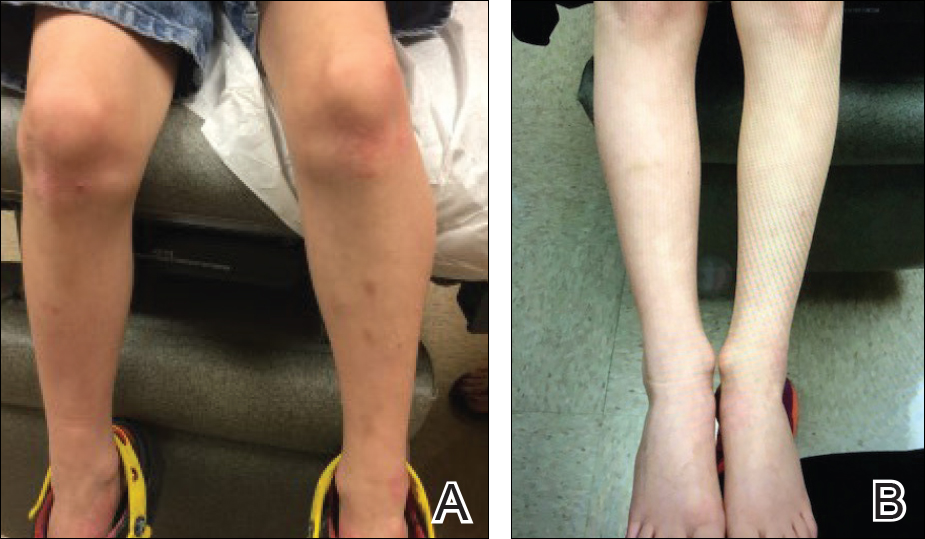

The patient was eager to continue dupilumab therapy due to considerable reduction of itching and elimination of lesions. His mother reported that the greatest benefit 1 month after starting dupilumab was almost no itching (Figure 3A). Additionally, he denied headache or nasopharyngitis at his 1-month office visit. After 2 months of dupilumab therapy, the patient reported persistent lesions on the feet and ankles despite concomitant treatment with topical corticosteroids. The decision to increase the dupilumab dose to 300-mg SQ injection once every 3 weeks for a total of 3 doses was made, which resulted in resolution of all lesions (Figure 3B). A once-monthly SQ injection schedule was reintroduced after week 17, and dose adjustments are anticipated in the future.