Patient 3

A 27-year-old woman who gave birth 2 years prior and discontinued breastfeeding 6 weeks after delivery noted bilateral breast rashes for several months. The lesions were growing in size, tender, and draining. Her primary care provider suspected infectious mastitis and prescribed antibiotics, which were ineffective.

Biopsy

Breast core biopsy showed histologic findings similar to patients 1 and 2, including lobulocentric mixed inflammation, neutrophilic microabscesses, and scattered discrete granulomas. Microorganisms were not found using special stains. Breast cancer was ruled out, and granulomatous mastitis was diagnosed.

Referral to Dermatology

Two years earlier, the patient tested positive for latent tuberculosis and was prescribed a 9-month regimen of isoniazid. At the current presentation, she did not have symptoms of active tuberculosis on ROS (ie, no cough, hemoptysis, weight loss, night sweats); a chest radiograph was normal. Additionally, serum Ca2+ and ACE levels as well as an ophthalmology examination were normal, and she was not taking any medications known to increase the prolactin level.

The patient was started on methotrexate (12.5 mg weekly) and folic acid (1 mg daily). She had 1 IGM flare and was given a tapering regimen of prednisone. She received methotrexate for 14 months, tapered during the final 3 months. She has been off methotrexate for 3 years without IGM flares and appears to be in complete remission.

COMMENT

We report 3 cases of IGM, which contribute to the literature on possible presentations, causes, and conservative treatment of this rare connective-tissue disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

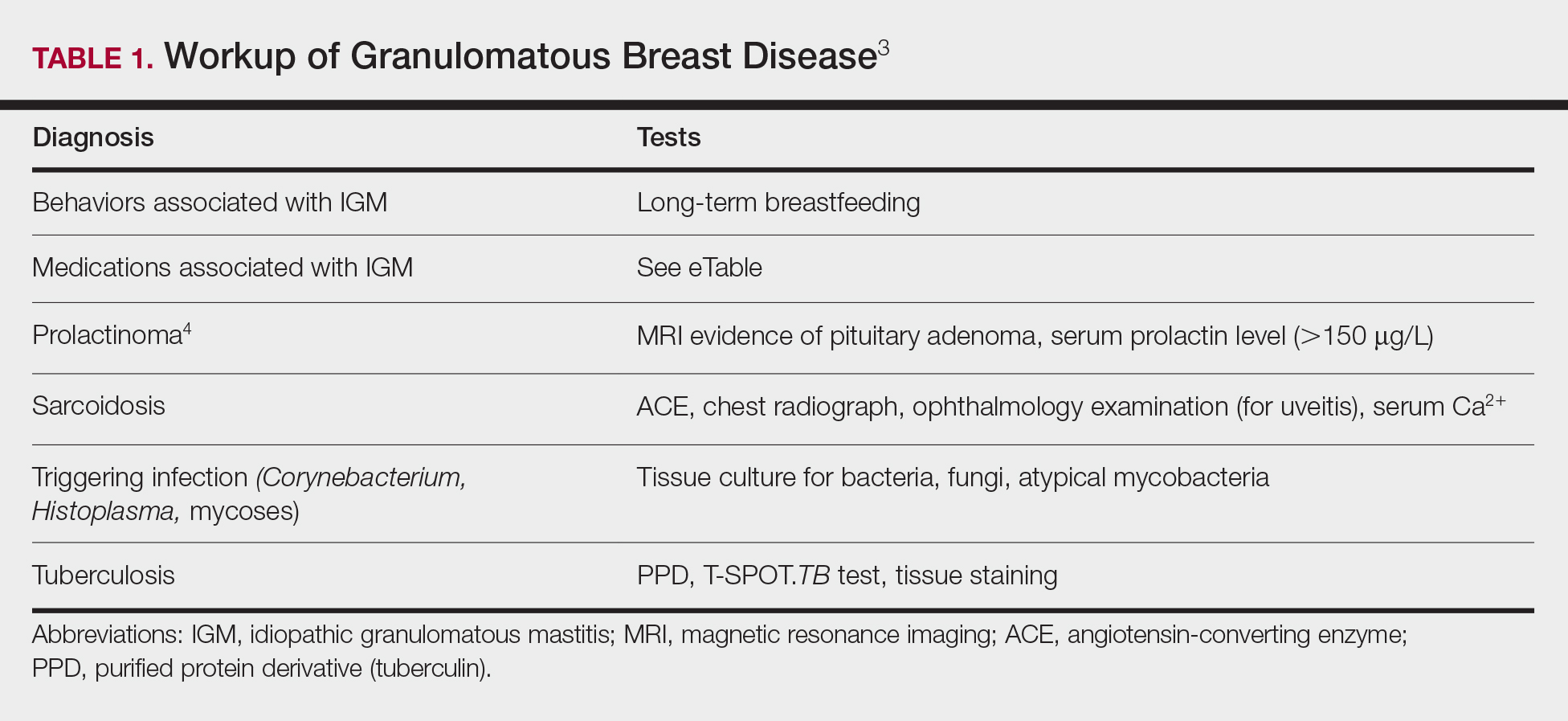

The time between recognition of symptoms and diagnosis and treatment of IGM often is prolonged because IGM can present similarly to other disorders, such as infection, breast cancer, tuberculosis, and sarcoidosis. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is a diagnosis of exclusion, made after obtaining evidence of granulomatous inflammation on breast biopsy and ruling out other granulomatous disorders, such as tuberculosis and sarcoidosis (Table 1).3,4

Tuberculosis

A full ROS and a PPD test or T-SPOT.TB test can be helpful in ruling out tuberculosis; because anergy occurs in some patients, tuberculosis should be evaluated in the context of known immunosuppression or human immunodeficiency virus status, or in the case of miliary tuberculosis.

Chest radiography findings classically showing upper lobe infiltrates with cavities in active tuberculosis also should be sought.3 Ziehl-Neelsen staining of 2 sputum specimens, assessed by conventional light microscopy at the time of tissue biopsy has 64% sensitivity and 98% specificity for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis; auramine O staining, examined with light-emitting diode fluorescence microscopy, has 73% sensitivity and 93% specificity.5

Sarcoidosis

Because more than 90% of sarcoid patients have lung disease, a chest radiograph is used to screen for hilar lymphadenopathy.3 An elevated serum ACE level also can be helpful in diagnosis, but patients do not always have increased ACE, which can occur in other diseases, such as hyperthyroidism and miliary tuberculosis. Sarcoid granulomas can increase active vitamin D production, which in turn increases serum Ca2+ in 10% of sarcoid patients. Last, an ophthalmology evaluation should be obtained to rule out anterior or posterior uveitis that can occur in sarcoidosis and initially remain asymptomatic.3 Once these other causes of granulomatous inflammation have been ruled out, a diagnosis of IGM can be made.

Prolactinoma

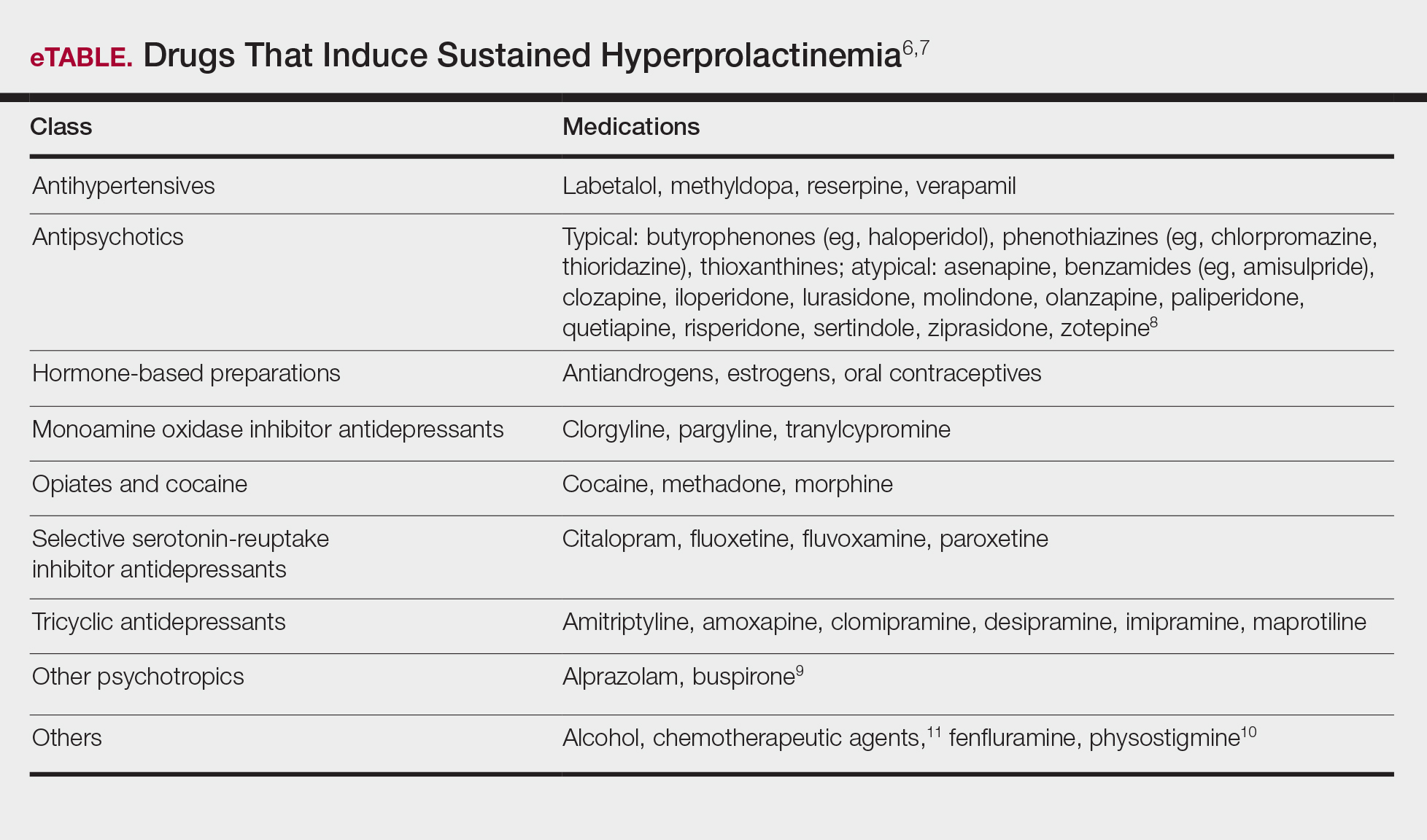

Prolactinoma is an important cause of hyperprolactinemia that can be screened for based on ROS and the serum prolactin level. Prolactinoma can cause oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea and galactorrhea in 90% and 80% of premenopausal women, respectively, as well as erectile dysfunction and decreased libido in men. Infertility, headache, and visual impairment may be experienced in both sexes.4

A normal prolactin level is less than 25 μg/L; more than 25 μg/L but less than 100 μg/L usually is due to certain drugs (eTable),6-11 estrogen, or idiopathic reasons; and more than 150 μg/L usually is due to prolactinoma.5 In many cases, removal of hyperprolactinemia-precipitating factors can resolve disease, as in patient 1. If symptoms continue or precipitating factors are absent, IGM symptom-based treatment should be administered.