Comment

Clinical Presentation

Cutaneous TB is an uncommon manifestation of TB that can occur either exogenously or endogenously.1 It tends to occur primarily in previously infected TB patients through hematogenous, lymphatic, or contiguous spread.2 Due to their immunocompromised state, solid organ transplant recipients have an increased incidence of primary and reactivated latent TB reported to be 20 to 74 times greater than the general population.3,4 One report stated the total incidence of posttransplant TB as 0.48% in the West and 11.8% in endemic regions such as India.5 The occurrence of cutaneous TB is rare among solid organ transplant recipients.1 On average, a diagnosis of latent TB is made 9 months after transplantation because of the opportunistic nature of M tuberculosis in an immunosuppressed environment.6

TB Subtypes

Cutaneous TB can be in the form of localized disease (eg, primary tuberculous chancre, TB verrucosa cutis, lupus vulgaris, smear-negative scrofuloderma), disseminated disease (eg, disseminated TB, TB gumma, orificial TB, miliary cutaneous TB), or tuberculids (eg, papulonecrotic tuberculid, lichen scrofulosorum, erythema induratum).7 Due to the pustular epithelioid cell granulomas and AFB positivity of the involved cutaneous lesions, our patient’s TB can be classified as a metastatic TB abscess or gummatous TB.7

Metastatic TB abscess, an uncommon subtype of cutaneous TB, generally is only seen in malnourished children and notably immunocompromised individuals.2,8,9 In these individuals, systemic failure of cell-mediated immunity enables M tuberculosis to hematogenously infect various organs of the body, resulting in alternative forms of TB, such as gummatous-type TB.10 One study reported that of the 0.1% of dermatology patients presenting with cutaneous TB, only 5.4% of these individuals had the rarer gummatous form.7 These metastatic TB abscesses begin as a single or multiple nontender subcutaneous nodule(s), which breaks down and softens to form a draining sinus abscess.2,8,9 Abscesses are most commonly seen on the trunk and extremities; however, they can be found nearly anywhere on the body.8 The pathology of cutaneous TB lesions demonstrates caseating necrosis with epithelioid and giant cells forming a surrounding rim.9

Diagnosis

Diagnosis may be difficult because of the vast number of dermatologic conditions that resemble cutaneous TB, including mycoses, sarcoidosis, leishmaniasis, leprosy, syphilis, other non-TB mycobacteria, and Wegener granulomatosis.9 Thus, confirmatory diagnosis is made via clinical presentation, detailed history and physical examination, and laboratory tests.11 These tests include the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (PPD or TST) or IFN-γ release assays (QuantiFERON-TB Gold test), identification of AFB on skin biopsy, and isolation of M tuberculosis from tissue culture or polymerase chain reaction.11Given our patient’s history, clinical presentation, and the identification of mycobacteria with AFB stain, the diagnosis of cutaneous gummatous TB was confirmed.

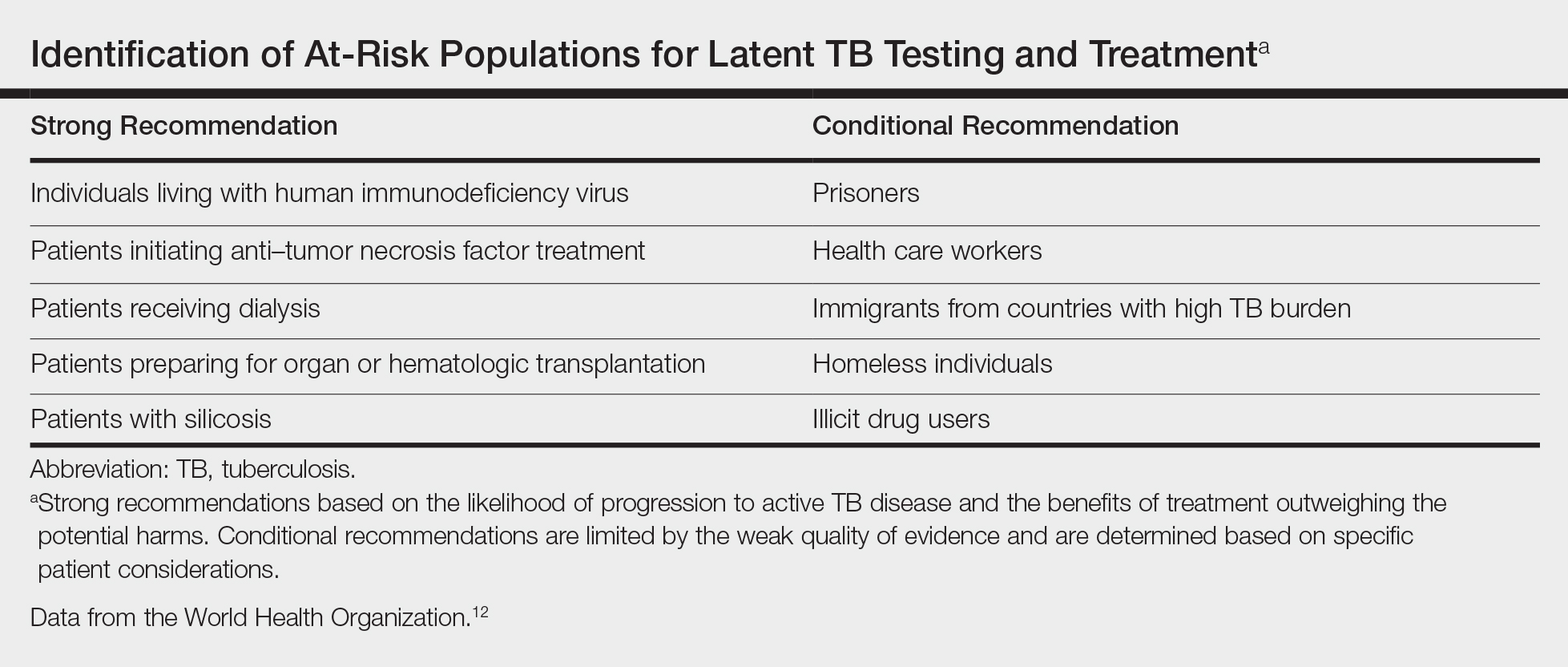

At-Risk Populations

The recommendation for the identification of at-risk populations for latent TB testing and treatment have been clearly defined by the World Health Organization (Table).12 Our patient met 2 of these criteria: she had been preparing for organ transplantation and was from a country with high TB burden. Such at-risk patients should be tested for a latent TB infection with either IFN-γ release assays or PPD.12These recommendations are supported by the American Thoracic Society, which specifies that a positive PPD test in a solid organ transplant recipient is defined as having induration greater than 5 mm.13 However, even with a high index of suspicion, it has been reported that as many as 75% to 80% of organ recipients who developed TB had a false-negative pretransplantation PPD due to anergy from immunosuppression.14 Given the notable risk for TB in organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressive medications, these patients should receive screening tests with high sensitivity and specificity, while controlling for possible anergy. Unfortunately, the role of anergy testing in the diagnosis of latent TB is not well defined, and thus not recommended at this time.13,15 It is recommended to repeat PPD testing 7 to 10 days after the first test as a booster effect to rule out false-negative results.15

Treatment

The recommended treatment of active TB in transplant recipients is based on randomized trials in immunocompetent hosts, and thus the same as that used by the general population.16 This anti-TB regimen includes the use of 4 drugs—typically rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide—for a 6-month duration.11 Unfortunately, the management of TB in an immunocompromised patient is more challenging due to the potential side effects and drug interactions.

Finally, thrombocytopenia is an infrequent, life-threatening complication that can be acquired by immunocompromised patients on anti-TB therapy.17 Drug-induced thrombocytopenia can be caused by a variety of medications, including rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Diagnosis of drug-induced thrombocytopenia can be confirmed only after discontinuation of the suspected drug and subsequent resolution of the thrombocytopenia.17 Our patient initially became thrombocytopenic while taking isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin. However, her platelet levels improved once the pyrazinamide was discontinued, thereby suggesting pyrazinamide-induced thrombocytopenia.

Conclusion

The risk for infectious disease reactivation in an immunocompromised patient undergoing transplant surgery is notable. Our findings emphasize the value of a comprehensive pretransplant evaluation, vigilance even when test results appear negative, and treatment of latent TB within this population.16,18,19 Furthermore, this case illustrates a noteworthy example of a rare form of cutaneous TB, which should be considered and included in the differential for cutaneous lesions in an immunosuppressed patient.