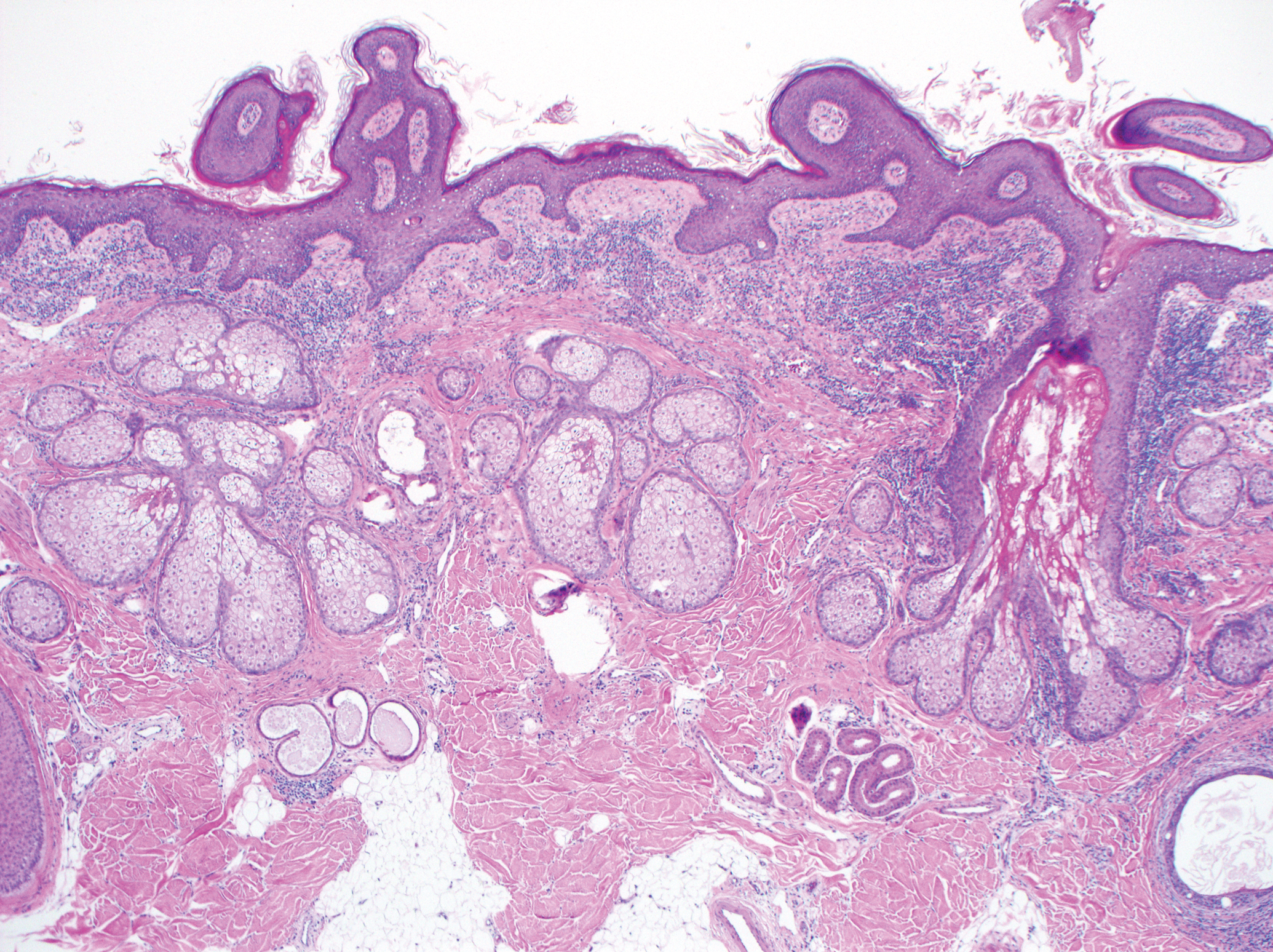

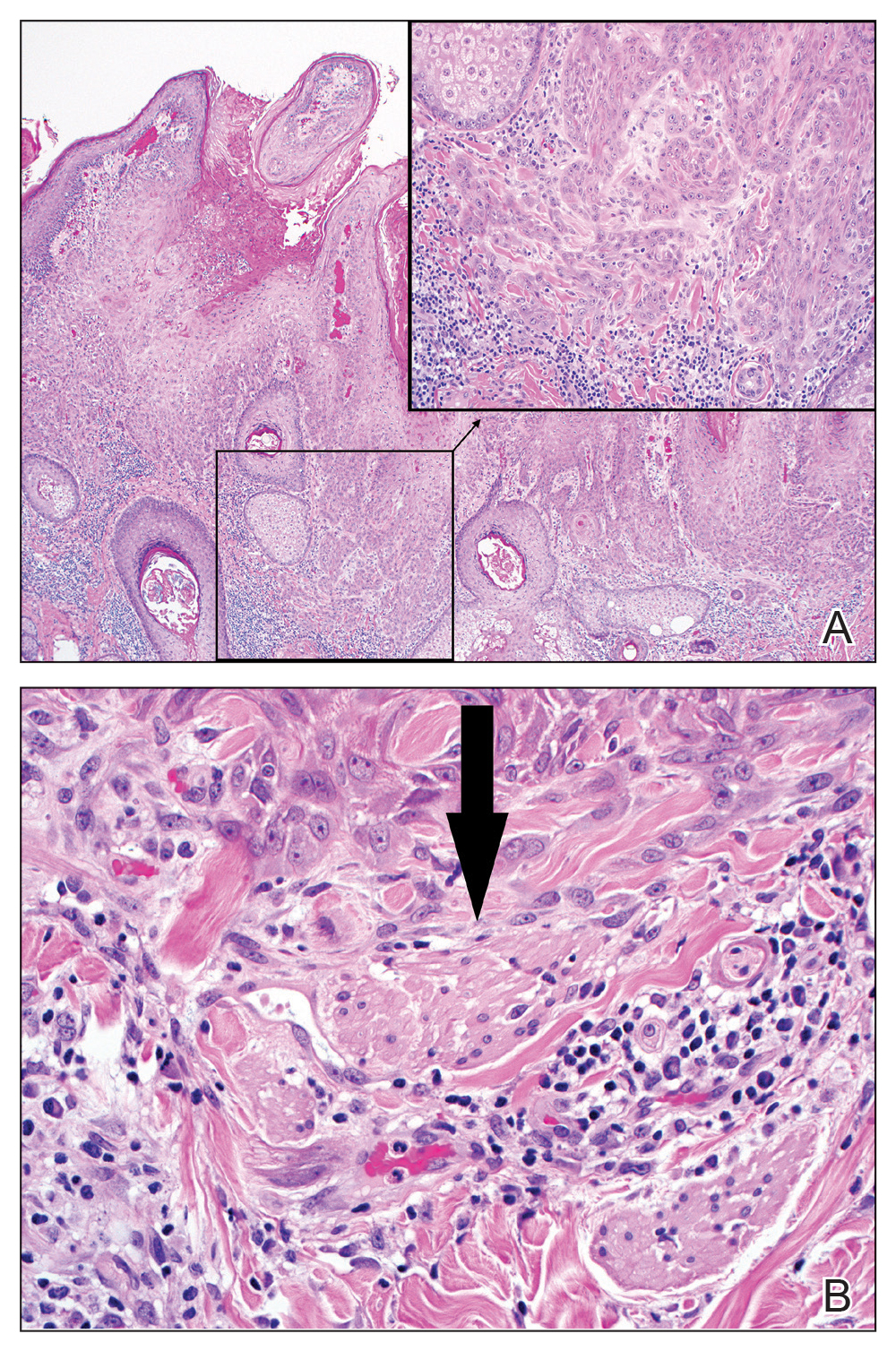

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

Figure 3. A, Highly verrucous epidermal proliferation with atypical squamous cells in lower right corner (H&E, original magnification ×40). The inset showed perineural invasion of the superficial dermis (H&E, original magnification ×200). B, An additional focus showed invasive squamous cell carcinoma surrounded by a small superficial nerve fiber (arrow)(H&E, original magnification ×400).

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.