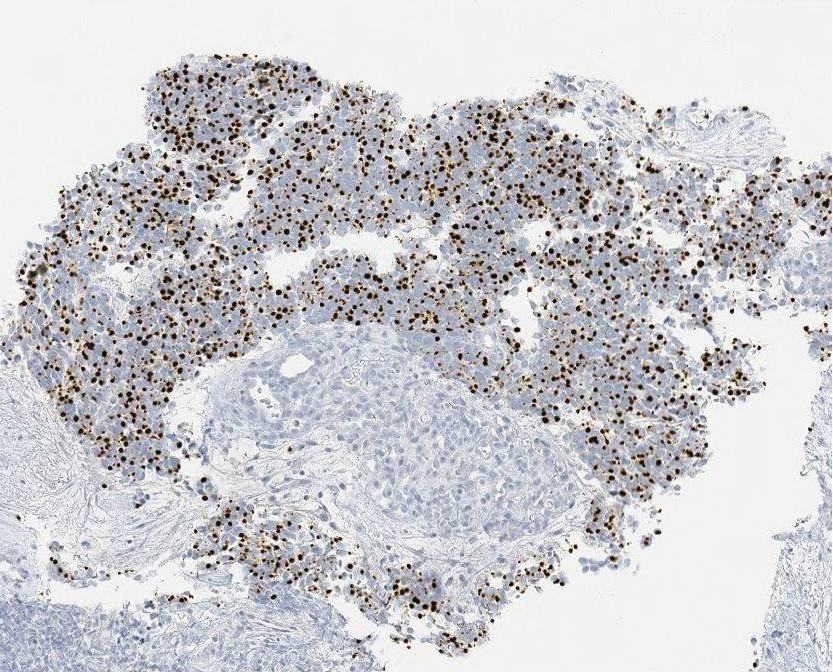

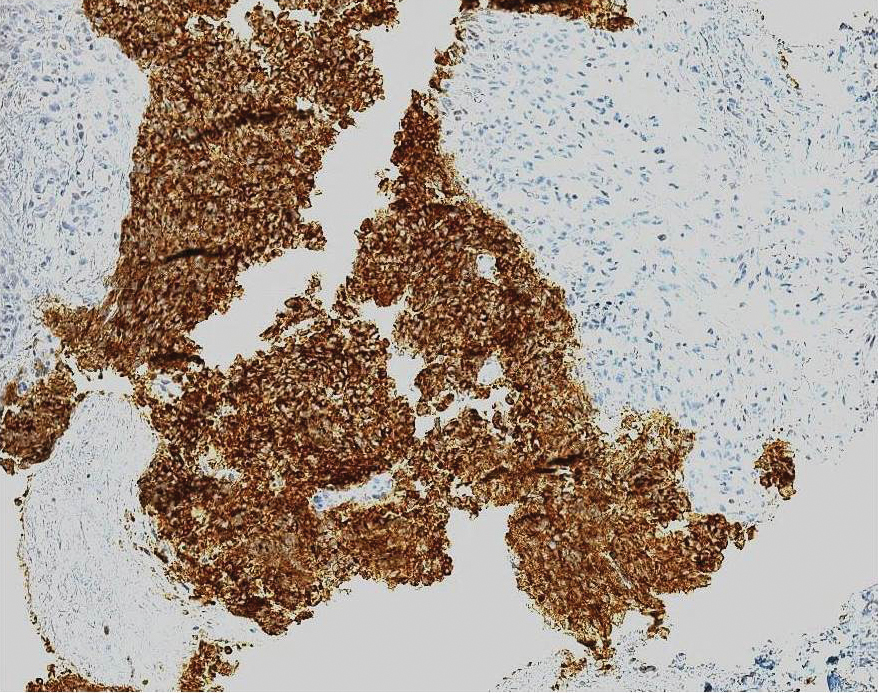

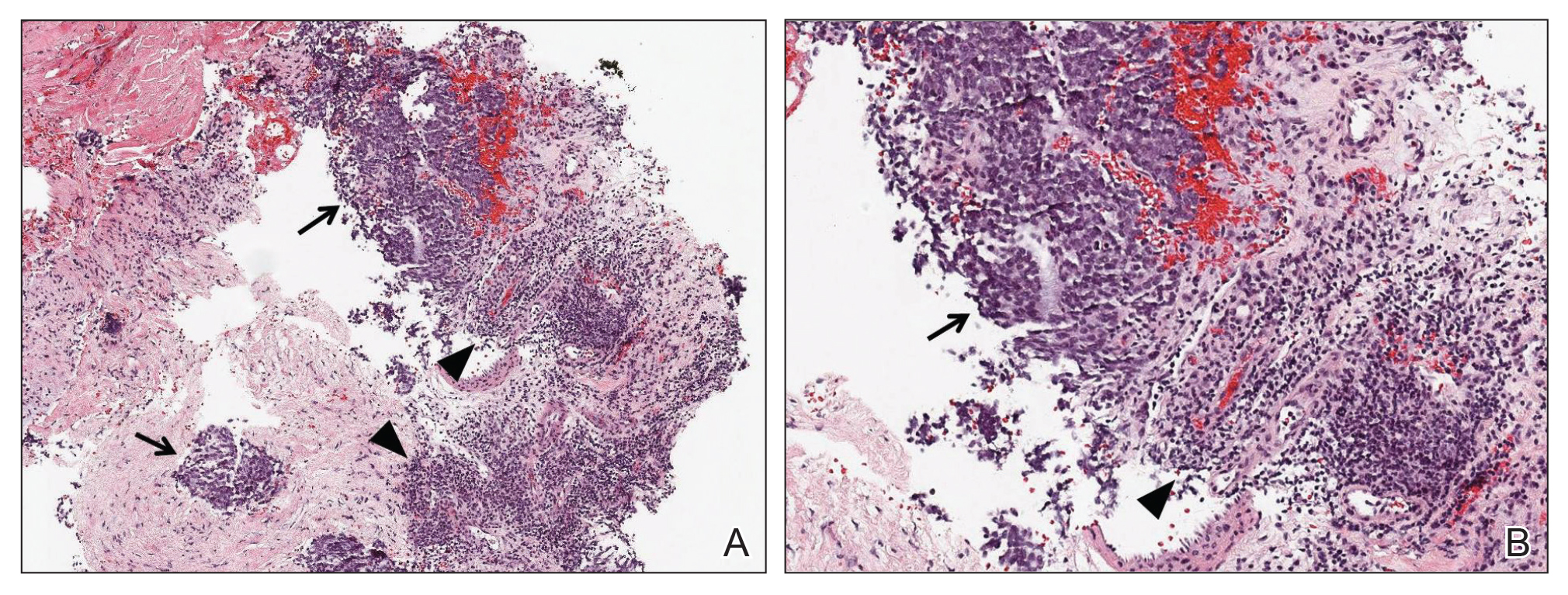

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the enlarged axillary lymph nodes demonstrated sheets and nests of small round blue tumor cells with minimal cytoplasm, high mitotic rate, and foci of necrosis (Figure 1). The tumor cells were positive for pancytokeratin (Lu-5) and cytokeratin (CK) 20 in a perinuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2), as well as for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin (Figure 3), chromogranin A, and CD56. The tumor cells showed no immunoreactivity for CK7, thyroid transcription factor 1, CD3, CD5, or CD20. Flow cytometry demonstrated low cellularity, low specimen viability, and no evidence of an abnormal B-cell population. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of MCC.

Figure 1. A, Biopsy of axillary lymph nodes demonstrated small round blue tumor cells (arrows), associated lymphoid tissue (arrowheads), and fibrous stroma (H&E, original magnification ×40). B, Higher magnification further contrasted the small round blue tumor cells (arrow) and associated lymphocytes (arrowhead)(H&E, original magnification ×200).

The patient underwent surgical excision of the involved lymph nodes. Four weeks after surgery, he reported dramatic improvement in strength, with complete resolution of the nasal speech, dysphagia, dry mouth, urinary retention, and constipation. Two months after surgery, his strength had normalized, except for slight persistent weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, trace weakness in the hip flexors, and a slight Trendelenburg gait. He was able to rise from a chair without using his arms and no longer required a cane for ambulation.

The patient underwent adjuvant radiation therapy after 2-month surgical follow-up with 5000-cGy radiation treatment to the left axillary region. Six months following primary definitive surgery and 4 months following adjuvant radiation therapy, he reported a 95% subjective return of physical strength. The patient was able to return to near-baseline physical activity. He continued to deny symptoms of dry mouth, incontinence, or constipation. Objectively, he had no focal neurologic deficits or weakness; no evidence of new skin lesions or lymphadenopathy was noted.

Comment

MCC vs SCLC

Merkel cell carcinoma is classified as a type of EPSCC. The histologic appearance of MCC is indistinguishable from SCLC. Both tumors are composed of uniform sheets of small round cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and both can express neuroendocrine markers, such as neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin.9 Immunohistochemical positivity for CK20 and neurofilaments in combination with negative staining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and CK7 effectively differentiate MCC from SCLC.9 In addition, MCC often displays CK20 positivity in a perinuclear dotlike or punctate pattern, which is characteristic of this tumor.3,9,10 Negative immunohistochemical markers for B cells (CD20) and T cells (CD3) are important in excluding lymphoma.

LEMS Diagnosis

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder involving the neuromuscular junction. Autoantibodies to VGCC impair calcium influx into the presynaptic terminal, resulting in marked reduction of acetylcholine release into the synaptic cleft. The reduction in acetylcholine activity impairs production of muscle fiber action potentials, resulting in clinical weakness. The diagnosis of LEMS rests on clinical presentation, positive serology, and confirmatory neurophysiologic testing by NCS. Clinically, patients present with proximal weakness, hyporeflexia or areflexia, and autonomic dysfunction. Antibodies to P/Q-type VGCCs are found in 85% to 90% of cases of LEMS and are thought to play a direct causative role in the development of weakness.11 The finding of postexercise facilitation on motor NCS is the neurophysiologic hallmark and is highly specific for the diagnosis.

Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who present with LEMS have an underlying tumor, the vast majority of which are SCLC.11 There are a few reports of LEMS associated with other malignancies, including lymphoma; thymoma; neuroblastoma; and carcinoma of the breast, stomach, prostate, bladder, kidney, and gallbladder.12 Patients with nontumor or autoimmune LEMS tend to be younger, and there is no male predominance, as there is in paraneoplastic LEMS.13 Given the risk of underlying malignancy in LEMS, Titulaer et al14 proposed a screening protocol for patients presenting with LEMS, recommending initial primary screening using CT of the chest. If the CT scan is negative, total-body fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography should be performed to assess for fludeoxyglucose avid lesions. If both initial studies are negative, routine follow-up with CT of the chest at 6-month intervals for a minimum of 2 to 4 years after the initial diagnosis of LEMS was recommended. An exception to this protocol was suggested to allow consideration to stop screening after the first 6-month follow-up chest CT for patients younger than 45 years who have never smoked and who have an HLA 8.1 haplotype for which nontumor LEMS would be a more probable diagnosis.14

In addition to a screening protocol, a validated prediction tool, the Dutch-English LEMS Tumor Association prediction score, was developed. It uses common signs and symptoms of LEMS and risk factors for SCLC to help guide the need for further screening.15