Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with a lifetime prevalence of 15% to 20% in industrialized countries.1 It affects both children and adults and is predominantly characterized by a waxing and waning course of eczematous skin lesions and pruritus. In recent years, there is increasing recognition that AD can present with extracutaneous findings. Large-scale epidemiologic studies have reported a notably higher prevalence of ophthalmic complications in the AD population compared to the general population, in a severity-dependent manner.2,3 Potential complications include blepharitis, keratoconjunctivitis, keratoconus, glaucoma, cataracts, retinal detachment, ophthalmic herpes simplex virus infections, and dupilumab-associated ocular complications.

The etiology of each ocular complication in the context of AD is complex and likely multifactorial. Intrinsic immune dysregulation, physical trauma from eye rubbing, AD medication side effects, and genetics all have been speculated to play a role.2 Some of these ocular complications have a chronic course, while others present with sudden onset of symptoms; many of them can result in visual impairment if undiagnosed or left untreated. This article reviews several of the most common ocular comorbidities associated with AD. We discuss the clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management strategies for each condition.

Blepharitis

Blepharitis, an inflammatory condition of the eyelids, is estimated to affect more than 6% of patients with AD compared to less than 1% of the general population.2 Blepharitis can be classified as anterior or posterior, based on the anatomic location of the affected region relative to the lash margin. Affected individuals may experience pruritus and irritation of the eyelids, tearing, a foreign body or burning sensation, crusting of the eyelids, and photophobia.4 Anterior blepharitis commonly is due to staphylococcal disease, and posterior blepharitis is secondary to structural changes and obstruction of meibomian gland orifices.

Although the pathophysiology is not well defined, xerosis in atopic patients is accompanied by barrier disruption and transepidermal water loss, which promote eyelid skin inflammation.

The mainstay of therapy for atopic blepharitis consists of conventional lid hygiene regimens, such as warm compresses and gentle scrubbing of the lid margins to remove crust and debris, which can be done with nonprescription cleansers, pads, and baby shampoos. Acute exacerbations may require topical antibiotics (ie, erythromycin or bacitracin applied to the lid margins once daily), topical calcineurin inhibitors (ie, cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05%), or low-potency topical corticosteroids (ie, fluorometholone 0.1% or loteprednol etabonate 0.5% ophthalmic suspensions).5 Due to potential side effects of medications, especially topical corticosteroids, patients should be referred to ophthalmologists for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Keratoconjunctivitis

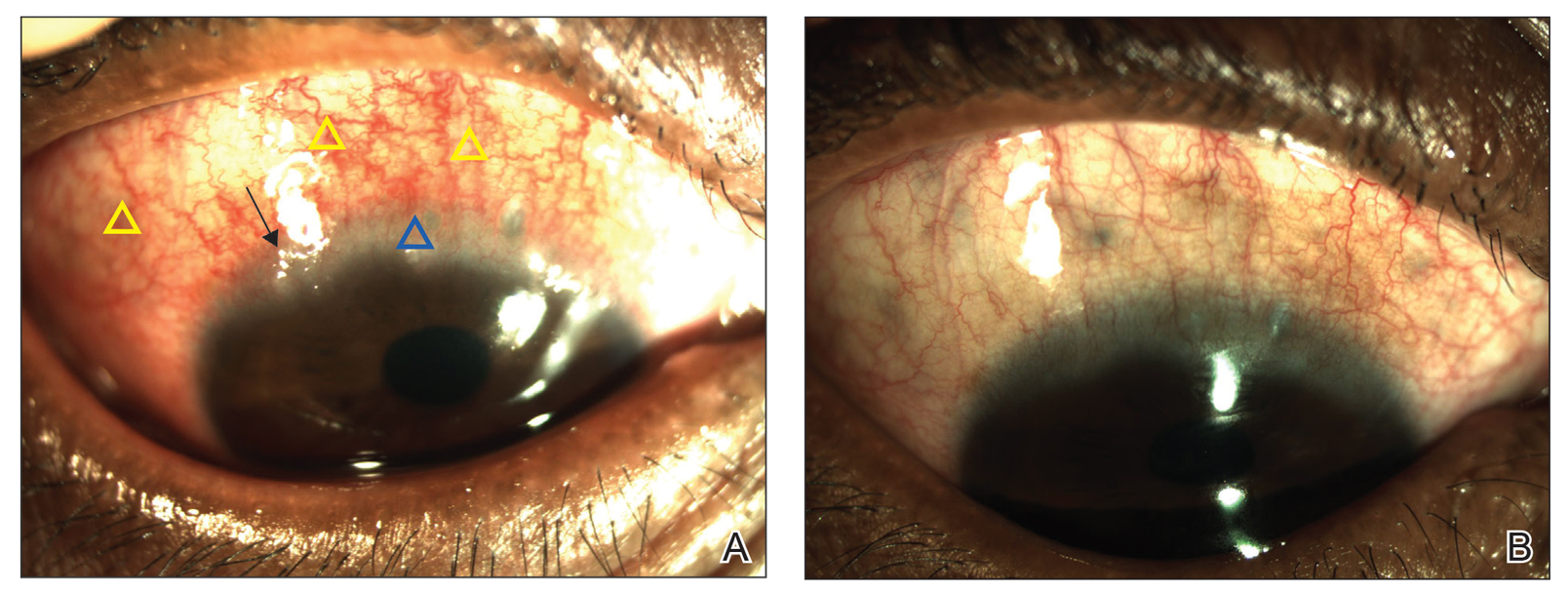

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) is a noninfectious inflammatory condition of the cornea and conjunctiva that occurs in an estimated 25% to 42% of patients with AD.6,7 It frequently presents in late adolescence and has a peak incidence between 30 and 50 years of age.8 The symptoms of AKC include ocular pruritus, redness, ropy mucoid discharge, burning discomfort, photophobia, and blurring of vision. Corneal involvement can progress to corneal neovascularization and punctate or macroepithelial erosions and ulcerations, which increase the risk for corneal scarring and visual impairment.7

Keratoconjunctivitis is a complex inflammatory disease characterized by infiltration of the conjunctival epithelium by eosinophils, mast cells, and lymphocytes. On examination, patients frequently are found to have concurrent AD of the periorbital skin as well as papillary hypertrophy of the tarsal conjunctiva with accompanying fibrosis, which can lead to entropion (turning inward of the lid margins and lashes) in severe cases.7 Ophthalmic evaluation is strongly recommended for patients with AKC to control symptoms, to limit exacerbations, and to prevent sight-threatening inflammation leading to vision loss. Treatment can be challenging given the chronicity of the condition and may require multiple treatment arms. Conservative measures include cool compresses and treatment with ophthalmic eye drops containing antihistamines (ie, ketotifen 0.025% [available over-the-counter]) and mast cell stabilizers (ie, olopatadine ophthalmic solution 0.1%).8 Atopic keratoconjunctivitis exacerbations may require short-term use of topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors, or systemic equivalents for refractory cases.6 Long-term maintenance therapy typically consists of proper eye hygiene and steroid-sparing agents that reduce ocular inflammation, such as topical cyclosporine and tacrolimus, neither of which are associated with increased intraocular pressure (IOP)(Figure 1).8 Cornea disease resulting from chronic conjunctival/lid microtrauma can be managed with soft or scleral contact lenses.