Patient 3

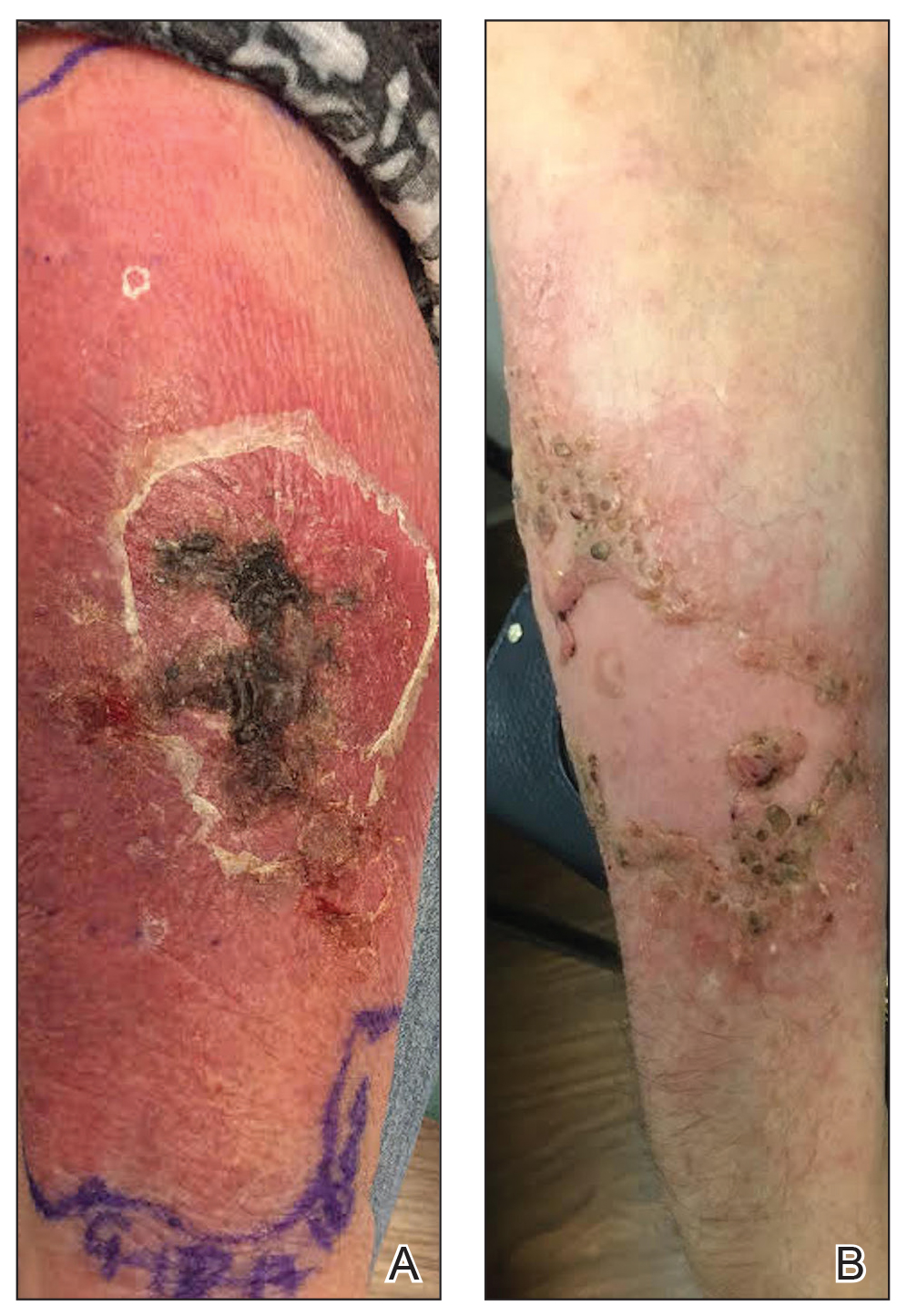

A 77-year-old woman with a history of rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate and abatacept as well as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma treated with narrowband UVB radiation presented to the emergency department with fever and an inflamed right forearm (Figure 3A). Initial bacterial cultures of the wound and blood were negative.

The patient was treated with vancomycin and discharged on cephalexin once she became afebrile. She was seen at our office the next week for further evaluation. We recommended that she discontinue all immunosuppressant medications. A 4-mm tissue biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and a separate 4-mm punch biopsy for culture were performed while she was taking cephalexin. Histopathologic analysis revealed numerous neutrophilic abscesses; however, Gram, AFB, and fungal stains were negative.

Arm edema and pustules slowly resolved, but the eschar and verrucous plaques continued to slowly progress while the patient was off immunosuppression. She was kept off antibiotics until mycobacterial culture was positive at 4 weeks, at which time she was placed on doxycycline and clarithromycin. Final identification of M haemophilum was made at 6 weeks; consequently, doxycycline was discontinued and she was referred to infectious disease for multidrug therapy. She remained afebrile during the entire 6 weeks until cultures were final.

While immunosuppressants were discontinued and clarithromycin was administered, the plaque changed from an edematous pustular dermatitis to a verrucous crusted plaque. Neither epitrochlear nor axillary lymphadenopathy was noted during the treatment period. The infectious disease specialist prescribed azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifampin, which produced marked improvement (Figure 3B). The patient has remained off immunosuppressive therapy while on antibiotics.

Comment

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Mycobacterium haemophilum is a rare infectious organism that affects primarily immunocompromised adults but also has been identified in immunocompetent adults and pediatric patients.2 Commonly affected immunosuppressed groups include solid organ transplant recipients, bone marrow transplant recipients, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, and patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

The infection typically presents as small violaceous papules and pustules that become painful and erythematous, with progression and draining ulceration in later stages.2 In our cases, all lesions tended to evolve into a verrucous plaque that slowly resolved with antibiotic therapy.

Due to the rarity of this infection, the initial differential diagnosis can include infection with other mycobacteria, Sporothrix, Staphylococcus aureus, and other fungal pathogens. Misdiagnosis is a common obstacle in the treatment of M haemophilum due to its rarity, often negative AFB stains, and slow growth on culture media; therefore, tissue culture is essential to successful diagnosis and management. The natural reservoir of M haemophilum is unknown, but infection has been associated with contaminated water sources.1 In one case (patient 1), symptoms developed after a dog scratch; the other 2 patients were unaware of injury to the skin.Laboratory diagnosis of M haemophilum is inherently difficult and protracted. The species is a highly fastidious and slow-growing Mycobacterium that requires cooler (30°C) incubation for many weeks on agar medium enriched with hemin or ferric ammonium citrate to obtain valid growth.1 To secure timely diagnosis, the organism’s slow agar growth warrants immediate tissue culture and biopsy when an immunocompromised patient presents with clinical features of atypical infection of an extremity. Mycobacterium haemophilum infection likely is underreported because of these difficulties in diagnosis.