Nonbiologic Systemic Therapies

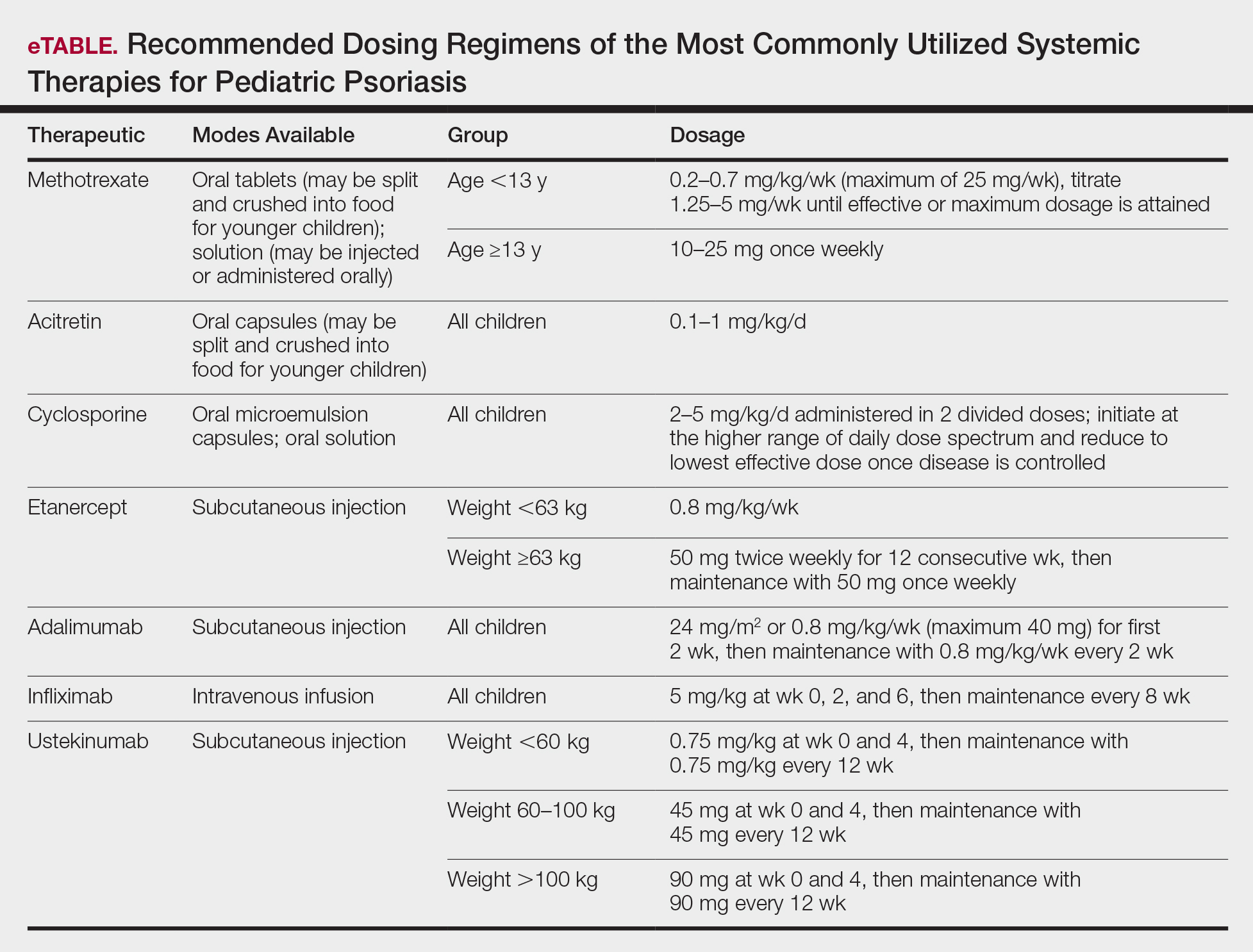

Systemic therapies may be considered in children with recalcitrant, widespread, or rapidly progressing psoriasis, particularly if the disease is accompanied by severe emotional and psychological burden. These drugs, which include methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin (see eTable for recommended dosing), are advantageous in that they may be combined with other therapies; however, they have potential for dangerous toxicities.

Methotrexate is the most frequently utilized systemic therapy for psoriasis worldwide in children because of its low cost, once-weekly dosing, and the substantial amount of long-term efficacy and safety data available in the pediatric population. It is slow acting initially but has excellent long-term efficacy for nearly every subtype of psoriasis. The most common side effect of methotrexate is gastrointestinal tract intolerance. Nonetheless, adverse events are rare in children without prior history, with 1 large study (N=289) reporting no adverse events in more than 90% of patients aged 9 to 14 years treated with methotrexate.12 Current guidelines recommend monitoring for bone marrow suppression and elevated transaminase levels 4 to 6 days after initiating treatment.1 The absolute contraindications for methotrexate are pregnancy and liver disease, and caution should be taken in children with metabolic risk factors. Adolescents must be counseled regarding the elevated risk for hepatotoxicity associated with alcohol ingestion. Methotrexate therapy also requires 1 mg folic acid supplementation 6 to 7 days a week, which decreases the risk for developing folic acid deficiency and may decrease gastrointestinal tract intolerance and hepatic side effects that may result from therapy.

Cyclosporine is an effective and well-tolerated option for rapid control of severe psoriasis in children. It is useful for various types of psoriasis but generally is reserved for more severe subtypes, such as generalized pustular psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, and uncontrolled plaque psoriasis. Long-term use of cyclosporine may result in renal toxicity and hypertension, and this therapy is absolutely contraindicated in children with kidney disease or hypertension at baseline. It is strongly recommended to evaluate blood pressure every week for the first month of therapy and at every subsequent follow-up visit, which may occur at variable intervals based on the judgement of the provider. Evaluation before and during treatment with cyclosporine also should include a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, and lipid panel.

Systemic retinoids have a unique advantage over methotrexate and cyclosporine in that they are not immunosuppressive and therefore are not contraindicated in children who are very young or immunosuppressed. Children receiving systemic retinoids also can receive routine live vaccines—measles-mumps-rubella, varicella zoster, and rotavirus—that are contraindicated with other systemic therapies. Acitretin is particularly effective in pediatric patients with diffuse guttate psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, and palmoplantar psoriasis. Narrowband UVB therapy has been shown to augment the effectiveness of acitretin in children, which may allow for reduced acitretin dosing. Pustular psoriasis may respond as quickly as 3 weeks after initiation, whereas it may take 2 to 3 months before improvement is noticed in plaque psoriasis. Side effects of retinoids include skin dryness, hyperlipidemia, and gastrointestinal tract upset. The most severe long-term concern is skeletal toxicity, including premature epiphyseal closure, hyperostosis, periosteal bone formation, and decreased bone mineral density.1 Vitamin A derivatives also are known teratogens and should be avoided in females of childbearing potential. Lipids and transaminases should be monitored routinely, and screening for depression and psychiatric symptoms should be performed frequently.1

When utilizing systemic therapies, the objective should be to control the disease, maintain stability, and ultimately taper to the lowest effective dose or transition to a topical therapy, if feasible. Although no particular systemic therapy is recommended as first line for children with psoriasis, it is important to consider comorbidities, contraindications, monitoring frequency, mode of administration (injectable therapies elicit more psychological trauma in children than oral therapies), and expense when determining the best choice.

Biologics

Biologic agents are associated with very high to total psoriatic plaque clearance rates and require infrequent dosing and monitoring. However, their use may be limited by cost and injection phobias in children as well as limited evidence for their efficacy and safety in pediatric psoriasis. Several studies have established the safety and effectiveness of biologics in children with plaque psoriasis (see eTable for recommended dosing), whereas the evidence supporting their use in treating pustular and erythrodermic variants are limited to case reports and case series. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor etanercept has been approved for use in children aged 4 years and older, and the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab is approved in children aged 6 years and older. Other TNF-α inhibitors, namely infliximab and adalimumab, commonly are utilized off label for pediatric psoriasis. The most common side effect of biologic therapies in pediatric patients is injection-site reactions.1 Prior to initiating therapy, children must undergo tuberculosis screening either by purified protein derivative testing or IFN-γ release assay. Testing should be repeated annually in individuals taking TNF-α inhibitors, though the utility of repeat testing when taking biologics in other classes is not clear. High-risk patients also should be screened for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis. Follow-up frequency may range from every 3 months to annually, based on judgement of the provider. In children who develop loss of response to biologics, methotrexate can be added to the regimen to attenuate formation of efficacy-reducing antidrug antibodies.

Final Thoughts

When managing children with psoriasis, it is important for dermatologists to appropriately educate guardians and children on the disease course, as well as consider the psychological, emotional, social, and financial factors that may direct decision-making regarding optimal therapeutics. Dermatologists should consider collaboration with the child’s primary care physician and other specialists to ensure that all needs are met.

These guidelines provide a framework agreed upon by numerous experts in pediatric psoriasis, but they are limited by gaps in the research. There still is much to be learned regarding the pathophysiology of psoriasis; the risk for developing comorbidities during adulthood; and the efficacy and safety of certain therapeutics, particularly biologics, in pediatric patients with psoriasis.