Dr. Aziz Sancar and colleagues at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill and the North Carolina State University in Raleigh conducted a study in hairless mice to see if the cyclical nature of a particular type of DNA repair might also influence the onset of skin cancer.

Dr. Sancar had already proven that a protein called XPA, which helps repair UV-related DNA damage, is primarily controlled by the circadian clock.

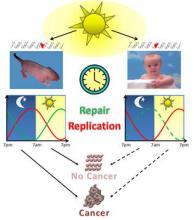

XPA activity reaches its peak between the hours of 4 p.m. and 6 p.m. and is at its lowest between 4 a.m. and 6 a.m. in mice, according to the study published in the early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (doi:10.1073/pnas.1115249108).

They analyzed the expression pattern of XPA and its excision repair activity in mouse skin. One group of mice were exposed to UVB when repair activity was at its lowest in the morning, and another group was exposed when repair activity was at its peak, at 4 p.m.

Mice that were exposed when repair activity was low developed skin cancers faster and five times more frequently than mice exposed when repair activity was at its peak.

The authors reported that the human circadian clock is almost identical to the mouse clock, but that humans run on a diurnal pattern, while mice on a nocturnal pattern. Thus, humans are more susceptible to UV radiation in the late afternoon hours.

"Our research would suggest that restricting sunbathing or visits to the tanning booth to morning hours would reduce the risk of skin cancer in humans," said Dr. Sancar, in a statement issued by the UNC. Dr. Sancar is also a member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Dermatologists might be a little miffed at Dr. Sancar's suggestion that there is a safe time to tan. But if his findings hold up, it might at least give physicians some leeway with patients who insist on getting some UV exposure. Maybe there will be a small window where getting sun is not as dangerous.

The researchers did note that findings "must be considered provisional until actual DNA repair rates are measured in the skin of human volunteers." That study is being planned.

Dr. Sancar's research received funding from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

- Alicia Ault (on Twitter @aliciaault)