VAIL, COLO. – Misconceptions abound regarding the appropriate use of diagnostic serologic testing for Lyme disease. The end result is needless difficulties for patients, families, and their physicians, Dr. Roberta L. DeBiasi asserted at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases.

The first point to understand about serologic testing is that it isn’t even guideline recommended in patients who have early localized Lyme disease in the form of erythema migrans. Erythema migrans is a clinical diagnosis that in and of itself is sufficient to trigger the decision to treat.

"This is a major pitfall we see: A child or adult comes in with a classic rash of erythema migrans and the physician decides to do the serology. It comes back negative because the sensitivity and specificity of serologic testing at that stage is abysmal. So the patient’s Lyme disease goes untreated," she explained.

Children with untreated early-stage Lyme disease have up to a 50% risk of later developing Lyme arthritis, a 10% risk of Lyme meningitis, and a 5% risk of Lyme chronic carditis, according to Dr. DeBiasi, acting chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

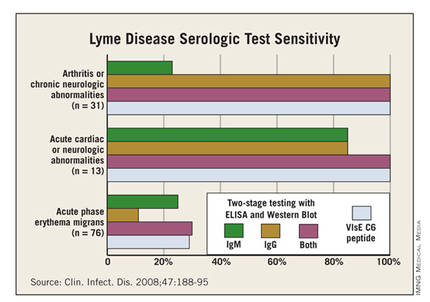

While there’s absolutely no point in doing serology in patients with early cutaneous disease manifestations only, the test sensitivity is far better in patients with extracutaneous manifestations of disease, such as meningitis, carditis, or arthritis. This was demonstrated in a classic study led by Dr. Allen C. Steere, professor of rheumatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who is credited with recognizing and naming the full syndrome he called Lyme disease (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;47:188-95).

Dr. Steere and his colleagues showed that, while the sensitivity of standard two-tiered testing was a mere 30% in the setting of acute-phase erythema migrans, it jumped to 100% in patients with arthritis, chronic neurologic abnormalities, or acute cardiac or neurologic abnormalities.

Erythema migrans appears 3-30 days and a median of 11 days after an Ixodes tick bite. It starts as a red macule or papule at the bite site and expands over days to weeks – not hours – eventually reaching a diameter of 5 cm or more, and in some cases as large as 30 cm. Circular or oval-shaped rashes are the most common. Partial clearing in the center, known as a bull’s eye, is common but not required. Up to 10% of patients with erythema migrans will have a small necrotic or vesicular/pustular are in the center of the lesion.

The most helpful features in distinguishing erythema migrans from similar-looking skin lesions are that it’s neither itchy nor painful.

"If it’s really itchy it’s usually an insect bite. If it really hurts it’s usually cellulitis," according to Dr. DeBiasi.

Differentiating erythema migrans from a tick bite hypersensitivity reaction, which is not an indicator of Borrelia burgdorferi infection, is a matter of the timing of the lesion’s onset and disappearance. Tick bite hypersensitivity reactions are erythematous lesions which appear while the tick is still attached or within 48 hours after detachment. That’s earlier than erythema migrans. And the hypersensitivity reaction typically begins to disappear 24-48 hours after its arrival; in contrast, erythema migrans grows larger during those first days after its initial appearance.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43:1089-134) recommend treating erythema migrans without neurologic or cardiac involvement with 14 days of oral therapy. The American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book recommends 14-21 days. The first-line options are doxycycline in patients above age 8 years, amoxicillin in those under that age, and cefuroxime. Macrolide antibiotics aren’t recommended as first-line therapy because they proved less effective in clinical trials. First-generation cephalosporins are ineffective. Intravenous ceftriaxone is no more effective than oral agents.

"You might be thinking, ‘Who in the world would use IV [intravenous] ceftriaxone for erythema migrans?’ but it happens all the time. In high-incidence areas for Lyme disease, we have lots of people who call themselves Lyme specialists who set up shop and put ads in the phone book. Patients who don’t know any better go to them and can get very dangerous treatments," Dr. DeBiasi explained.

Erythema migrans resolves within the first several days of appropriate antibiotic therapy, although the oft-accompanying flu-like systemic symptoms may linger for several weeks.

Dr. DeBiasi conceded Lyme serology is confusing, even for infectious disease physicians. The key message is that it must always be a two-step process: Use an enzyme immunoassay or immunofluorescence assay as a screening test and, if it’s positive or equivocal, send the specimen for a standard IgM/IgG Western immunoblot. Antibodies aren’t detectable in the first few weeks of infection but by week 4 the screening test will pick up nearly all B. burgdorferi–infected individuals, albeit with a 5%-7% false-positive rate.