Case Scenarios

Case 1

You had just started your shift, and your first patient presented with symptoms of headache and dizziness, and a blood pressure (BP) of 240/130 mm Hg, without any vomiting or visual symptoms. Physical examination revealed an alert, pleasant 65-year-old black man whose ocular, neurological, and cardiovascular (CV) examinations were normal. The patient reported a history of borderline hypertension, but had never taken any medications for it.

After placing some initial orders, including an electrocardiogram (ECG), basic metabolic panel (BMP), and head computed tomography (CT) scan, and ordering 10 mg intravenous (IV) prochlorperazine and 25 mg IV diphenhydramine to treat the patient’s headache, you are left asking yourself what steps you should take next.

Case 2

Your next patient was a 90-year-old white woman who had been referred to the ED by her primary care physician (PCP) for “hypertensive urgency.” She had no complaints to report. Similar to the first patient, this patient’s physical examination was also normal, with the exception of a persistently elevated BP of 220/140 mm Hg. Her history was significant for congestive heart failure (CHF), but she exhibited no current CV signs or symptoms. The patient had been taking furosemide but was not on any other antihypertensive medications.

Case 3

In the room next to your 90-year-old patient is a 32-year-old uninsured hypertensive white woman. During the history taking, the patient stated that she was trying to become pregnant and was not currently using any form of contraception. Similar to the second patient, she had no complaints to report. Regarding her reason for presentation, the patient stated that when she had her BP checked at a pharmacy earlier that day, the reading was “too high,” and the pharmacist had advised her to go to the ED. She seemed anxious but otherwise well. Her initial BP at presentation was 240/100 mm Hg, but her physical examination was otherwise normal.

Hypertensive Emergencies

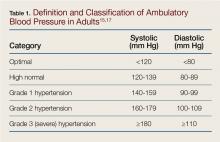

As emergency physicians (EPs), we see hypertensive patients every day. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 33% of American adults have hypertension, which is defined by a BP of ≥140/90 mm Hg (Table 1).

Hypertension remains uncontrolled in over 50% of these patients1 and contributes to a large disease burden, including stroke, CV disease, and kidney failure. Treatment of hypertension has been proven effective in reducing morbidity and mortality.2Almost 25% of total annual US adult ED visits are directly or indirectly related to hypertension, and about 1% of all ED visits are due solely to elevated BP.3 In an ambulatory care survey for 2007, moderate or severe hypertensive BP readings were found to be more common in patients presenting to the ED (43.5%) than to primary care clinics (27%).4 Patients presenting to the ED with hypertensive BP readings disproportionately represented patients who were older, male, non-Hispanic black, Medicare beneficiaries, or uninsured. Certainly, some patients presenting to the ED have hypertensive BP readings due to pain or anxiety, but multiple studies have suggested that 50% to 70% of ED patients who have hypertensive BP readings will be diagnosed with hypertension on office follow-up.5,6 While a minority of these patients present to the ED with hypertensive emergencies, the majority present either without symptoms of hypertension or with only mild headache. Given the disease burden of hypertension combined with the benefits of treatment, it is worthwhile for the practicing EP to review the most up-to-date guidelines on outpatient management of hypertension.

When a patient presents to the ED with a hypertensive BP reading, the initial priority of the EP is to exclude hypertensive emergency. Hypertensive emergencies are defined by the presence of hypertension (generally grade 3/severe hypertension with BP ≥180/110 mm Hg; see Table 1) in conjunction with evidence of target organ damage.

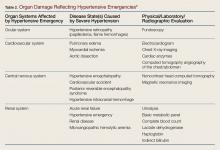

The organs that manifest the complications of severe hypertension and their associated hypertensive emergencies are listed in Table 2. The organs affected include the heart and vascular system, eyes, brain, and kidneys.Target Organ Manifestations

The acuity and/or presence of target organ damage are not always clear on initial ED evaluation. For instance, when a patient who has no history of primary care presents to the ED with severe hypertension, laboratory evaluation may demonstrate protein and blood in his or her urine and an elevated serum creatinine level. In the absence of values from past laboratory studies, it is difficult to determine whether these test results represent normal laboratory parameters for this patient due to longstanding hypertensive kidney disease (ie, hypertensive nephrosclerosis) or if they represent a true hypertensive emergency, (ie, hypertensive emergency-related nephropathy).7 In patients with severe hypertension and possibly new acute kidney injury, it is probably safest to either assume hypertensive emergency-related nephropathy and to treat accordingly or consult with nephrology services. The picture of hypertensive emergency-related nephropathy often only becomes clear after renal biopsy results and improvement in renal parameters with BP control.