Management

Initiating Antihypertensive Treatment

Some EPs may feel that an accurate diagnosis of hypertension requires repeat BP testing in the primary care office setting, and for this reason are reluctant to initiate antihypertensive treatment in the ED. The most recent guidelines by the Joint National Committee (JNC 8) do not address how many BP readings are necessary to diagnose hypertension, but JNC 7 suggested that diagnosis of hypertension requires two separate office visits.17 Evidence cited in ACEP’s first clinical policy states that two separate BP measurements in the ED are adequate for screening—but not necessarily for initiating treatment.10 However, European and British outpatient clinical recommendations advocate initiation of antihypertensive medication for a single visit in patients who have an elevated BP categorized as grade 3/severe hypertension (BP of ≥180/110 mm Hg).15,18 Furthermore, for patients with severe hypertension seen in the ED, as many as 97% are likely to have true hypertension at office follow-up.6 Those ED patients presenting with severe hypertension are very likely to have a true diagnosis of hypertension.

A recent retrospective analysis of a group of hypertensive ED patients by Brody et al19 found that patients prescribed BP medications by an EP were more likely to have improved BP control at follow-up 2 weeks later. In their study, the decision to prescribe antihypertensive medications were at the discretion of the EP. Seventy-six patients were given one or more prescriptions for antihypertensive therapy, compared to a control group of 141 patients who were not given a prescription. On follow-up at 2 weeks, there was an 11 mm Hg greater reduction of BP in the group who received prescriptions compared to the control group. None of the patients in either group on follow-up had experienced any new neurological deficits, ischemic events, life-threatening anaphylactic reactions, or clinically significant hypotension.

The Cleveland Clinic study14 also reported on those patents given who received new prescriptions from the ED. Similar to the study by Brody et al,19 none of the 82 patients discharged to home from the ED with a new antihypertensive prescription had any major adverse event at 30-day follow-up.14

Pharmacological Treatment Recommendations

When choosing to treat patients with new prescriptions for antihypertensives, it is important to follow the most current outpatient treatment recommendations. In 2014, JNC 8 released new guidelines for the outpatient management of adults with hypertension.20 The panel issued recommendations based on its systematic review of randomized controlled trials on antihypertensive treatments. The key recommendations are as follows:

- In patients aged 60 years or older, initiate pharmacological treatment at a BP of ≥150/90 mm Hg.

- In patients aged 18 to 59 years, initiate pharmacological treatment at a BP of ≥140/90 mm Hg.

- In the general nonblack population, initial antihypertensive treatment should include a thiazide-type diuretic, a calcium channel blocker (CCB), an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I), or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).

- In the general black population, initial treatment should include a thiazide-type diuretic or a CCB.

- In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) (including black patients), initial (or add-on) antihypertensive treatment should include an ACE-I or ARB to improve kidney outcomes—but not both.

- If goal BP is not reached within 1 month of initial treatment, increase the dose of the initial drug or add a second agent (eg, thiazide-type diuretic, CCB, ACE-I, or ARB). If goal is not reached with two drugs, use the third drug from that list if no contraindications exist, but do not use both an ACE-I and an ARB together in the same patient.

Of note, JNC 8, in departure from JNC 7, no longer recommends beta-blockers as first-line therapy for isolated hypertension (there may be compelling alternate indications, such as atrial fibrillation or postmyocardial infarction (MI), such that a beta-blocker would still be the first medication considered). The reason for this stems from a single randomized controlled trial of 9,193 patients that found that despite equivalent BP reduction, use of a beta-blocker in comparison to an ARB resulted in a higher rate of a composite outcome of death, MI, or stroke.21 The main difference was a 25% relative risk reduction for stroke with use of an ARB (losartan) in comparison to a beta-blocker (atenolol). The most recent European guidelines still include beta-blockers among its first-line recommended BP medications, but do acknowledge that they are not as effective in reducing stroke incidence as other alternative medications.15 The European guidelines otherwise include the same list of first-line agents. The British guidelines mirror JNC 8 in terms of first-line antihypertensive medication choices.18

Since the release of JNC 8, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) has been published, and will likely impact future national recommendations on BP management. The SPRINT study was a randomized controlled trial enrolling over 9,000 hypertensive nondiabetic patients older than age 50 years that treated individuals to a standard BP goal (systolic BP of 140 mm Hg) versus an intensive BP goal (systolic BP of 120 mm Hg) over a 3.5-year period. The trial was stopped early for safety as a 25% mortality reduction was observed in the intensive treatment group (1.65 vs 2.19 deaths/y).22 This was in contrast to previous trials that had mostly failed to show this sort of benefit, though previous trials were smaller in number or included only diabetic patients.23 While it is likely that this trial may influence lowering treatment thresholds from the office, it is not likely to impact care from the ED.

The recommendations of JNC 8 do not necessarily coincide with current US EP practice. In the study by Brody et al,19 of patients provided ED antihypertensive prescriptions, 54% received thiazide-type diuretics, 26% ACE-I, 10% CCBs, and 6% beta-blockers. This is noteworthy because 96% of those in the study were black patients who would benefit most from either a thiazide or a CCB. Another recent study of ED patients showed that of patients who were both treated in the ED and discharged with antihypertensive medications, 34% received a diuretic prescription, 32% clonidine, 15% a beta-blocker, 19% an ARB or ACE-I, 12% a CCB, and 2% hydrazine.24 These results are important because according to many published guidelines, including JNC 8, clonidine is only considered one of several fourth-line options for severe resistant hypertension.15,18,20 Since clonidine use can be complicated by rebound hypertension, it is not an ideal agent to be prescribed de novo to patients in the ED. This is particularly true if these patients are not already on maximum doses of the three most recommended agents previously noted, or if there are concerns over patient compliance.

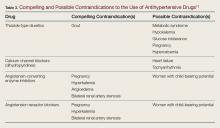

Of the drug classes recommended by JNC 8, Table 3 lists the absolute and relative contraindications.

Of note, potential side effects associated with thiazide diuretics are hypokalemia and hyponatremia. The ARB or ACE-I antihypertensives can worsen or induce hyperkalemia. For this reason, patients typically started on a thiazide should have periodic evaluation of sodium and potassium levels.15,17,25 Patients who have renal disease or who are at risk for renovascular disease should have repeat BMP evaluation 1 to 2 weeks after starting an ARB or ACE-I.26 Therefore, while ACEP may advise baseline testing of hypertensive patients is unnecessary, if choosing to start an ACE-I, ARB, or thiazide diuretic, a BMP should probably be checked. Oftentimes this will need to be repeated in the primary care office 1 to 2 weeks later. This may complicate choosing any of these agents from the ED.In clinical trials, amlodipine is among the most effective BP medications and is considered first-line therapy for all groups of patients with hypertension.15,18,20 A simplistic approach for most patients presenting with severe asymptomatic hypertension (BP of ≥180/110 mm Hg) not currently on treatment would be to recheck the BP and assure it remains elevated over the period of the ED visit.

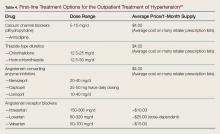

If it does, refer for follow- up, and consider prescribing amlodipine on ED discharge. In patients with baseline CKD or with history of CHF, consider alternatively starting them on an ARB or ACE-I. If starting an ARB or ACE-I, a baseline BMP should probably be checked and patients at risk for renovascular disease should be advised they require follow-up for repeat BMP in 1 to 2 weeks. Table 4 lists the commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications and typical dose ranges.