In 2013, 174,302 veterans had laboratory evidence of HCV viremia and could be characterized as having chronic HCV. HCV treatment regimens and response depend on the viral genotype. Among veterans with genotype testing, 107,144 (80%) have genotype 1; 15,486 (12%) genotype 2; 9,745 (7%) genotype 3; 1333 (1%) genotype 4; and 63 (< 1%) genotype 5 or 6.

In terms of demographics, most veterans with chronic HCV in VA care in 2013 were men (97%); however, > 5,000 women veterans with chronic HCV received care from the VA. Over half (54%) of veterans with chronic HCV are white, and about one-third (34%) are black. The proportion of blacks within the HCV-infected veteran population is substantially greater than the proportion of blacks in the overall veteran population in VA care (15%) and highlights the disproportionately large burden of HCV that black veterans bear. A smaller proportion of the VA HCV population is Hispanic (6%), and the remaining veterans are other races, multiple races, or unknown.

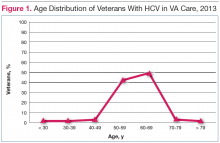

The HCV-infected veteran population is aging. The mean age of veterans with chronic HCV in 2013 was 59.7 years and for the first time, more veterans with HCV were aged 60 years (Figure 1).

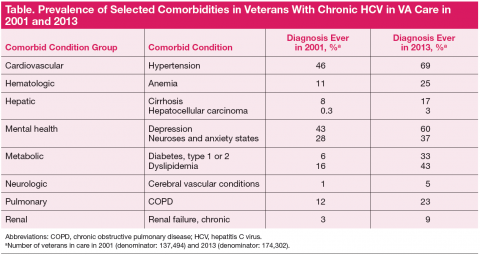

The aging population with HCV within the VA may impact the long-term management of other chronic conditions common in the elderly, including the potential need to adjust medications metabolized by the liver. The prevalence of many comorbid conditions associated with aging has increased in HCVinfected veterans with HCV since 2001. For example, diabetes has increased from 6% to 33% (Table).Among the comorbidities that may have historically prevented veterans from receiving HCV antiviral therapy, 2 of the most pervasive are mental health conditions and alcohol use. The rates of mental illness among veterans overall is high, but mental illness is particularly high in veterans with HCV. Depression has affected 60%; of this population anxiety, 37%; posttraumatic stress disorder, 28%; and schizophrenia, 10%. Alcohol use disorders are also common among veterans with HCV in care. Active mental health conditions and substance use may affect medication adherence or follow-up visit adherence thereby limiting treatment candidacy. Integrating care of these individuals with mental health providers and substance-use treatment specialists is an important aspect of HCV care and is a priority in VA.

Three-quarters (76%) of the HCV-infected veteran population has been screened for HIV and HIV-HCV co-infection is present in 5733 (3%) of veterans with HCV. HIV-HCV co-infection is associated with an increased progression of liver disease and may have implications for the selection of HCV antiviral agents because of drug interactions. Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-HCV co-infection rates are higher at 7%. HBV vaccination or documentation of HBV immunity in those without HBV infection is 78%.

With regard to specific liver complications, 5% to 20% of those infected with chronic HCV will develop cirrhosis over a period of 20 to 30 years, and 1% to 5% will die of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or cirrhosis. 6 Given the natural history of chronic HCV and the aging HCV veteran cohort, increasing numbers of conditions related to progression of liver disease are expected over time. This is most evident in the number of veterans with a diagnosis of cirrhosis, which has increased from approximately 10,000 veterans (8%) in care in 2001 to nearly 30,000 veterans (17%) in care in 2013 (Figure 2).