Related: DoD Healthy Base Initiative

The second infectious disease group included veterans diagnosed with any infectious disease (ICD-9-CM codes 001-139) that was not a PID. To be considered for inclusion in the other infectious disease group, a veteran must have been diagnosed with the illness at any point after separation. This group was created as a control group for comparing differences in health care use of the veterans diagnosed with a PID both before and after the rule change. The illnesses within each study group were distinct, thus no direct comparisons were made between the groups. Instead, the magnitude of the difference in use before and after the presumptive disease ruling was compared.

Statistical Analysis

It is possible to have multiple services performed during a single outpatient visit, services that will generate separate bills, thus appearing to be different visits. For the purposes of this study, only 1 visit per day was counted when constructing the monthly health care counts for the 12 months before and after the date of diagnosis of a PID or another infectious disease. A general linear model was created to assess differences in the number of outpatient visits pre- and postruling, adjusting for the number of unique illnesses a veteran had. To adjust for normality in the model, the inverse log of the count of outpatient visits was used in the procedure. P values were compared with an á level of 0.05 to determine significance.

Results

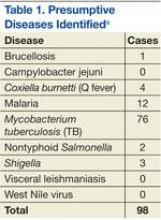

Among the 107,030 veterans receiving VHA care between June 28, 2009, and December 29, 2011, < 0.1% (n = 98) were in the PID group, and 7% (n = 7,603) were in the other infectious disease group (Tables 1 and 2). A significantly smaller proportion of active-duty (“regular”) veterans was in the PID group (50.0%) compared with the other infectious disease group (63.9%). Conversely, a significantly larger proportion of reserve or guard veterans werein the PID group (51.0%) compared with the other infectious disease group (36.1%) (P = .0089). The PID group included a higher proportion of Hispanic veterans (16.3%) and a lower proportion of black veterans (7.1%) than did the other infectious disease group.

The opposite was observed in the other infectious disease group: There was a lower proportion of Hispanic veterans (12.6%) and a higher proportion of black veterans (17.0%). Veterans whose military occupation status indicated combat experience were highly represented in each of the disease groups, as were males. Army veterans were disproportionately represented in the PID group (76.5%) compared with the other infectious disease group (65.4%), whereas the opposite was true for Marine Corps veterans (13.3% and 18.9%, respectively)(Table 2).

To assess the impact of the ruling on the health care-seeking behaviors of veterans, each group was further divided by the timing of diagnosis, specifically, before or after the PID ruling on September 29, 2010. Forty-five percent of the study population received a diagnosis prior to the ruling. Thirty-six percent of the PID group and 30% of the other infectious disease study groups were diagnosed before the ruling (Table 3).

Veterans in the other infectious disease group who were diagnosed after the PID ruling had a significantly higher total number of outpatient visits than did those diagnosed before the ruling (P < .05). A small increase was observed in the median number of outpatient visits among veterans diagnosed with a PID preruling (median = 7) compared with those diagnosed postruling (median = 8), but the difference was not statistically significant. Veterans in the preruling PID group received a diagnosis < 117 days (median value) after separation from service, whereas those in the postruling group received a diagnosis < 291 days (median value) after separation from service (Table 3).

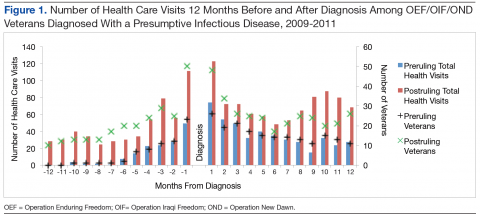

There was an increase in health care visits in the months directly before and after diagnosis, regardless of whether a veteran was diagnosed before or after the ruling. Figure 1 shows the total number of health care visits (visits for any condition) in the 12 months before and 12 months after a PID diagnosis, as well as the number of patients receiving care in those same months. In the months prior to receiving a diagnosis, the number of veterans receiving health care services followed the same trajectory as the total number of health care visits, regardless of the timing of the diagnosis. In the months after receiving a diagnosis, the trajectory for the total number of health care visits and the number of veterans generally followed the same path within the preruling group. In contrast, within the postruling group, the total number of visits was higher than the number of veterans, especially in the latter months, indicating that veterans were receiving services multiple times in a month.