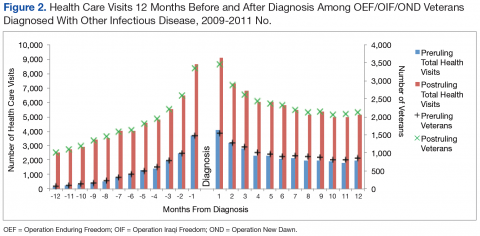

The patterns of health care use in the other infectious disease group were similar to those of the PID group, though the trajectories were more symmetrical for the other infectious disease pre- and postruling groups. There is a distinct increase in the total number of health care visits until diagnosis and a steady decrease in the 12 months after diagnosis with a leveling off of health care use toward the end of the observation period (Figure 2).

Discussion

The rate of PIDs in the U.S. was different from the observed rate in the study population, albeit a limited comparison. In the U.S. in 2010, the reported incidence per 100,000 persons was 0.04 for brucellosis, 13.52 for Campylobacter jejuni, 17.73 for nontyphoid Salmonella, and 0.2 for West Nile virus, vs no cases reported in the study.7,8 In contrast, the 2010-reported U.S. incidence rates per 100,000 persons with Q fever (0.04), malaria (0.58), and TB (3.64) were lower than those reported in the study population (3.32, 8.30, and 41.50 per 100,000 patients, respectively).7

Of the 107,030 OEF/OIF/OND veterans who received care during the study period, < 0.1% were diagnosed with a PIDs and 7% were diagnosed with a different infectious disease. Analysis indicated that 88 of the 98 PID were either TB or malaria cases. Thirty-six percent of the PID cases and 30% of the other infectious disease cases were diagnosed prior to the PID ruling. Veterans in the preruling PID and other infectious disease groups received a diagnosis within 4 or 5 months of becoming eligible for VHA services, whereas those in the postruling groups received a diagnosis within 10 months of eligibility, an observation that may have been caused by outliers and amplified by the small number of cases in the preruling PID group. However, this difference in time to diagnosis between the pre- and postruling groups does not seem to be a reflection of a delay in health care-seeking behavior in general: Veterans in both study groups sought VA services within 73 days of separating from active-duty service.

No significant difference in health care use was found between the pre- and postruling PID groups. When looking at the number of veterans receiving care each month and the total number of health care encounters, the ratio of encounters to veterans was less stable in the PID group than that of the other infectious disease group. Veterans with a PID received multiple outpatient services per month, especially in the postruling PID group. This may be a reflection of follow-up care needed for specific diseases.

Limitations

There are several limitations to note in the study. First, service members could have been diagnosed while still receiving health care services in the military health system, resulting in a low diagnosis rate within the VA. Second, the cases were identified solely based on ICD-9-CM codes; these are not confirmed diagnoses, and misclassification may occur. Future studies should consider incorporating laboratory results and other confirmatory methods of identification for case capture. A third limitation was the lack of availability of health care records outside of VHA. A large proportion of the study population was composed of the reserve/guard component. These veterans return to civilian jobs after separation and often have access to health care outside of VHA. Combined, these limitations affect the ability to identify the prevalence of infectious diseases among veterans.

Related: Women Using VA Health Care

Several findings could not be explored due to methodological limitations but warrant further exploration. First, the longer time period between eligibility and diagnosis post- vs preruling may be an indication that the ruling affected a veteran’s health care-seeking behavior. Second, it was possible that veterans presented with symptoms similar to one of the PIDs but were subsequently diagnosed with another infectious disease, which would affect the disease and use figures. Finally, studies should consider using confirmatory methods of diagnosis to assess the true prevalence of presumptive infectious diseases in the veteran population.

Conclusions

Very few PID cases were identified in the study population. This may be due to the limitation of the available data. However, some interesting findings such as a greater number of encounters for the infectious disease group post- vs preruling and differences in time between eligibility and diagnosis pre- and postruling were found and should be investigated further.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.