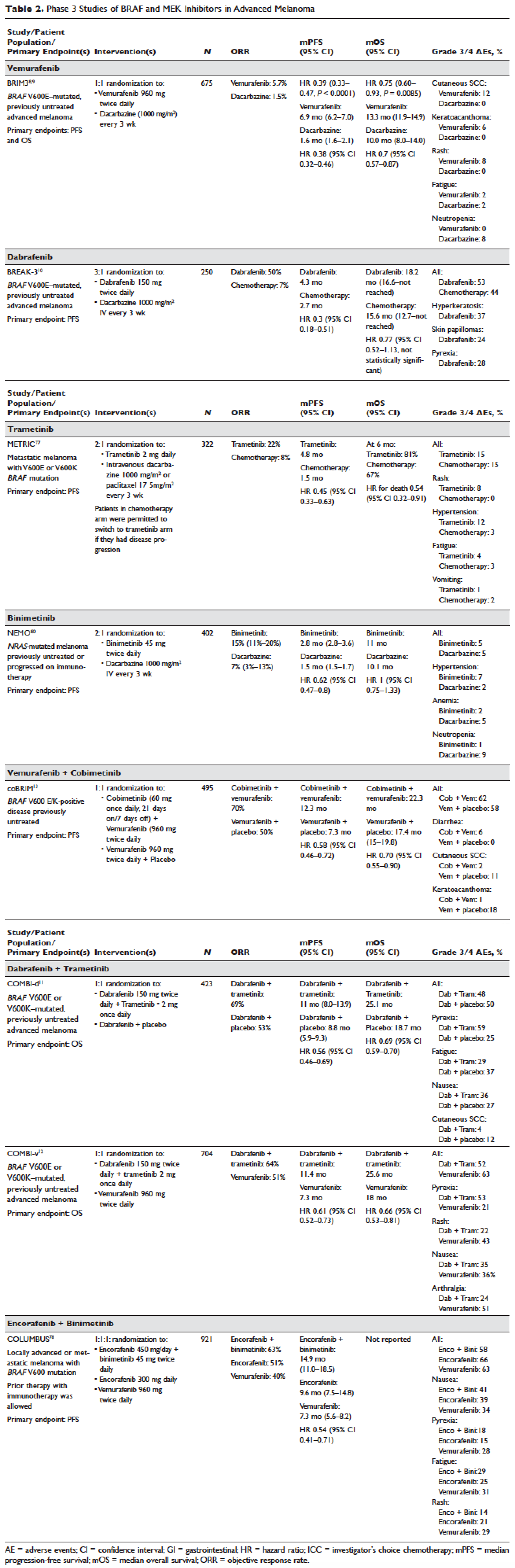

Vemurafenib and dabrafenib were evaluated in this tiered fashion in phase 1 dose-finding studies comprising unselected patients, followed by phase 2 studies in advanced BRAF V600E–mutated melanoma. Both were subsequently evaluated in randomized phase 3 trials (vemurafenib, BRIM-38; dabrafenib, BREAK-310) that compared them with dacarbazine (1000 mg/m2 intravenously every 3 weeks) in the treatment of advanced BRAF V600E–mutated melanoma. Response kinetics for both agents were remarkably similar: single-agent BRAF inhibitors resulted in rapid (time to response 2–3 months), profound (approximately 50% objective responses) reductions in tumor burden that lasted 6 to 7 months. Adverse events common to both agents included rash, fatigue, and arthralgia, although clinically significant photosensitivity was more common with vemurafenib and clinically significant pyrexia was more common with dabrafenib. Class-specific adverse events included the development of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas and keratoacanthomas secondary to paradoxical activation of MAPK pathway signaling either through activating mutations in HRAS or mutations or amplifications in receptor tyrosine kinases upstream of BRAF, resulting in elevated levels of RAS–guanosine triphosphate complexes.71 Results of these studies resulted in regulatory approval of single-agent BRAF inhibitors for the treatment of BRAF V600E (and later V600K)–mutated melanoma (vemurafenib in 2011; dabrafenib in 2013). Details regarding trial populations, study interventions, efficacy, and adverse events are summarized in Table 2.

Responses to BRAF inhibitors are typically profound but temporary. Mechanisms of acquired resistance are diverse and include reactivation of MAPK pathway–dependent signaling (RAS activation or increased RAF expression), and development of MAPK pathway–independent signaling (COT overexpression; increased PI3K or AKT signaling) that permits bypass of inhibited BRAF signaling within the MAPK pathway.72–76 These findings suggested that upfront inhibition of both MEK and mutant BRAF may produce more durable responses than BRAF inhibition alone. Three pivotal phase 3 studies established the superiority of combination BRAF and MEK inhibition over BRAF inhibition alone: COMBI-d11 (dabrafenib/trametinib versus dabrafenib/placebo), COMBI-v12 (dabrafenib/trametinib versus vemurafenib), and coBRIM13 (vemurafenib/cobimetinib versus vemurafenib/placebo). As expected, compared to BRAF inhibitor monotherapy, combination BRAF and MEK inhibition produced greater responses and improved progression-free and overall survival (Table 2). Interestingly, the rate of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas was much lower with combination therapy, reflecting the more profound degree of MAPK pathway inhibition achieved with combination BRAF and MEK inhibition. Based on these results, FDA approval was granted for both dabrafenib/trametinib and vemurafenib/cobimetinib combinations in 2015. Although the dabrafenib/trametinib combination was only approved in 2015, trametinib had independently gained FDA approval in 2013 for the treatment of BRAF V600E/K–mutated melanoma on the basis of the phase 3 METRIC study.77

Encorafenib (LGX818) and binimetinib (MEK162, ARRY-162, ARRY-438162) are new BRAF and MEK inhibitors currently being evaluated in clinical trials. Encorafenib/binimetinib combination was first evaluated in a phase 3 study (COLUMBUS) that compared it with vemurafenib monotherapy in BRAF-mutant melanoma.78 Unsurprisingly, encorafenib/binimetinib combination produced greater and more durable responses compared to vemurafenib monotherapy. The median progression-free survival of the encorafenib/binimetinib combination (14.9 months) was greater than vemurafenib monotherapy (7.3 months) in this study, and intriguingly greater than that seen with vemurafenib/cobimetinib (coBRIM 9.9 months) and dabrafenib/trametinib (COMBI-d 9.3 months; COMBI-v 11.4 months). Of note, although encorafenib has an IC50 midway between dabrafenib and vemurafenib in cell-free assays (0.8 nM dabrafenib, 4 nM encorafenib, and 31 nM vemurafenib), it has an extremely slower off-rate from BRAF V600E, which results in significantly greater target inhibition in cells following drug wash-out.79 This may account for the significantly greater clinical benefit seen with encorafenib/binimetinib in clinical trials. Final study data are eagerly awaited. Regulatory approval has been sought, and is pending at this time.

Binimetinib has been compared to dacarbazine in a phase 3 study (NEMO) of patients with NRAS-mutant melanoma, most of whom had been previously treated with immunotherapy.80 Response rates were low in both arms, although slightly greater with binimetinib than dacarbazine (15% versus 9%), commensurate with a modest improvement in progression-free survival. FDA approval has been sought and remains pending at this time.