Engineered T cells can produce durable responses in patients with Epstein Barr virus–positive (EBV+), relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

These T cells, known as DNRII-LSTs, produced responses in 4 of the 8 patients studied.

This included 3 complete responses (CRs), the longest of which has exceeded 7 years.

What’s more, these responses were achieved without the use of lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

“While the study is small, its findings are incredibly encouraging for our [patients’] families and for the cancer field,” said study author Catherine M. Bollard, MD, MBChB, of Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC.

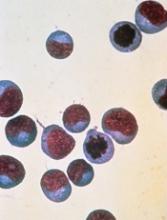

To engineer the DNRII-LSTs, Dr Bollard and her colleagues forced expression of a dominant-negative TGF-beta receptor type 2 (DNRII) on LMP-specific T cells (LSTs), which are T cells directed to the EBV latency-associated antigens LMP-1 and LMP-2.

The goal of forcing DNRII expression was to enable the LSTs to resist the hostile tumor environment so they could seek out and kill the tumor cells.

Dr Bollard and her colleagues administered DNRII-LSTs to 8 patients with EBV+ HL. The patients ranged in age from 27 to 47.

Seven of the 8 patients had active disease at the time of DNRII-LST infusion. Two patients had stage IVB HL, 1 had stage IIIB, and 2 had stage IIB. Four patients had nodular-sclerosing HL.

Six patients had relapsed twice. The remaining 2 patients had relapsed 3 and 4 times, respectively. All patients had previously received an autologous stem cell transplant and a range of multi-agent chemotherapy regimens (eg, ABVD, R-ICE, and MOPP).

For this study, the patients received 2 to 12 infusions of DNRII-LSTs, at doses ranging from 2 × 107 to 1.5 × 108 cells/m2.

Results

The researchers found that autologous DNRII-LSTs (given to 7 patients) did not cause autoimmunity, and donor-derived DNRII-LSTs (n=1) did not induce graft-vs-host disease.

The team also noted there were no toxicities resulting from cytokine release syndrome.

Four patients achieved a response to treatment—3 CRs and a partial response.

All complete responders are still in CR, but the partial responder progressed at 19 months and ultimately died of sepsis (2 years after the first dose of DNRII-LSTs).

The other 4 patients had stable disease (SD) for 4 months to 13 months after treatment with DNRII-LSTs.

One patient with SD died of disease progression 2 years after receiving DNRII-LSTs, and another died of transplant complications less than 2 years after the last dose of DNRII-LSTs.

One patient with SD went on to receive additional therapy and is still alive more than 6 years after receiving DNRII-LSTs (currently receiving nivolumab). Another SD patient went on to receive additional therapy, achieved a CR, and is still alive.

One of the patients who achieved a CR to DNRII-LSTs remains in CR more than 7 years after the last dose. Another patient’s CR has exceeded 2 years, and another’s has exceeded 5 years.

All 3 of these patients received doses of 2 × 107 cells/m2. The patients with the longest and shortest CRs each received 2 infusions of DNRII-LSTs. The patient with the CR exceeding 5 years received 12 infusions.

“These results come 18 years after this revolutionary approach was first conceptualized,” Dr Bollard said. “I started work in this area in 2000. At that time, the oncology community had little enthusiasm for the use of T-cell therapies to treat cancer.”

“Even then, when T-cell therapy was in its relative infancy, some research institutions began to see more than 90% complete responses and cure rates in some settings. This most recent study points to the potential of specialized T cells to fight even more types of immune-evading tumors.”