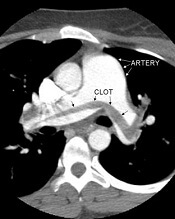

embolism; Credit: Medical

College of Georgia

Incorporating age into D-dimer test results can help clinicians more accurately diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE) in older patients, according to a new study.

Adjusting the D-dimer cutoff between abnormal and normal results according to a patient’s age allowed researchers to better differentiate healthy patients from those with PE.

The method did prove ineffective in 1 patient, who was ultimately diagnosed with venous thromboembolism (VTE).

But the remaining 300 patients who had D-dimer levels above the standard cutoff and below their age-adjusted cutoff were VTE-free during follow-up.

And among patients aged 75 and older, the age-adjusted cutoff safely excluded PE in about 30% of patients, whereas the standard cutoff excluded PE in about 6%.

Marc Righini, MD, of Geneva University Hospital in Switzerland, and his colleagues conducted this research and described their results in JAMA.

Previous studies showed that D-dimer levels increase with age. So the proportion of healthy patients with abnormal test results (above 500 µg/L for most tests) increases with age, and this limits the test’s utility in older patients.

Therefore, Dr Righini and his colleagues decided to determine whether an age-adjusted D-dimer threshold could safely exclude the diagnosis of PE in older patients. The team changed the cutoff between abnormal and normal results by multiplying the patient’s age by 10 in those 50 years or older.

The study included 3324 patients with suspected PE who first underwent a clinical probability assessment using either the simplified, revised Geneva score or the 2-level Wells score for PE.

If patients had a high clinical probability of PE (n=426), they underwent computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) and received treatment according to the results.

If PE was deemed unlikely, patients had a D-dimer test. Of these 2898 patients, 817 had normal results (< 500 μg/L), 337 had D-dimer levels ≥ 500 μg/L but below their age-adjusted cutoff, and 1744 had results higher than their age-adjusted cutoff.

Those 1744 patients joined the group of 426 who underwent CTPA (n=2170), and 631 of them were diagnosed with PE.

Of the 1539 patients who were not diagnosed with PE, 1481 completed the 3-month follow-up without receiving anticoagulant therapy. During that time, 7 of those patients had a confirmed VTE.

Of the 337 patients who had D-dimer levels ≥ 500 μg/L but below their age-adjusted cutoff, 331 completed follow-up without anticoagulation. And 1 of those patients was diagnosed with a VTE during that time.

Similarly, of the 817 patients who had normal D-dimer results, 810 completed follow-up without anticoagulation, and 1 patient was diagnosed with VTE.

So the age-adjusted D-dimer test and clinical probability assessment proved largely effective in identifying those patients at risk of VTE. But it also increased the proportion of elderly patients in whom PE could be safely excluded without further imaging.

Among the 766 patients aged 75 and older, 673 did not have a high clinical probability of PE. And using the age-adjusted cutoff instead of the 500 μg/L cutoff increased the proportion of patients in whom PE could be excluded from 6.4% (43/673) to 29.7% (200/673), without any additional false-negative findings.

The researchers said future studies should assess the utility of the age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff in clinical practice. It remains to be seen whether this method can decrease costs or improve the quality of care.