An international team of researchers has developed a blood test that identifies the 5%-10% of patients infected with latent tuberculosis who are likely to progress to active TB, up to 18 months before they show any sign of illness, according to a report published in the Lancet.

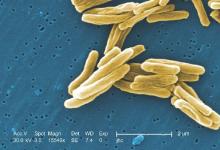

Worldwide, one-third of the apparently healthy population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but only a fraction will develop active TB during their lifetimes. Until now there has been no way to predict which of these people will progress and become ill. Treating all latently infected people in endemic areas for the necessary 6-9 months isn’t feasible, but a test that distinguishes which cases will become active would allow targeted preventive therapy. This could potentially interrupt the global spread of TB, said Daniel E. Zak, Ph.D. of the Center for Infectious Disease Research, Seattle, and his associates.

Such a test also might be used to assess treatment response, as well as to enroll only the highest-risk carriers of M. tuberculosis in trials of new drugs and vaccines, they added.

The investigators began by analyzing gene expression in peripheral whole-blood samples from 6,363 apparently healthy adolescents participating in a South African cohort study who were followed for 2-4 years for the development of active TB. They compared RNA-sequencing data from 46 participants who developed active TB against that from 107 matched control subjects who remained healthy and identified a candidate 16-gene risk signature for TB progression. “Robust discrimination between progressors and controls based on the expression of the gene pairs in the signature was readily apparent,” the researchers said.

In this subgroup of patients, the risk signature had a 71.2% sensitivity for predicting active TB during the 6 months preceding diagnosis, a 62.9% sensitivity during the 12 months preceding diagnosis, and a 47.7% sensitivity during the 18 months preceding diagnosis. The specificity was 80.6%.

To validate their findings, the investigators adapted the risk signature to a more practical PCR platform and used it to predict the risk of active TB in the remainder of the study population. The risk signature remained comparably sensitive and specific in this analysis.

To validate their findings in an independent cohort, Dr. Zak and his associates analyzed whole-blood samples from 4,466 apparently healthy adults from South Africa and the Gambia who were participating in a study of household contacts of patients with newly diagnosed active TB. During follow-up, 43 progressors and 172 control subjects were identified at the South African study site, and 30 progressors and 129 control subjects were identified at the Gambian study site. The risk signature again reliably distinguished patients who progressed from latent to active TB from those who didn’t progress, months before any sign of illness surfaced.

“When applied to combined data from 4 studies of HIV-uninfected South African adults involving 130 prevalent TB cases and 230 controls, the signature discriminated between patients with active TB and controls with 87% sensitivity and 97% specificity,” the investigators noted.

Adapting the risk signature further to microarrays so that it could be used in other datasets, the researchers found that it readily distinguished latent from active TB infection in stored samples from more cohorts from the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Malawi. In these cases the risk signature also distinguished active TB from other pulmonary diseases and from other diseases of childhood, and did so regardless of whether the study subjects were coinfected with HIV or not. “Finally, applying the signature to data from a treatment study showed that the active TB signature gradually disappears during 6 months of therapy,” Dr. Zak and his associates wrote (Lancet 2016 March 23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736[15]01316-1).

These latter observations suggest that the risk signature may reflect the TB bacterial load in the lung.

The study results were particularly encouraging given the marked diversity among these study populations. The participants had different age ranges, different infection or exposure status, distinct ethnic and genetic backgrounds, different local epidemiology, and different circulating strains of M. tuberculosis. “Our results … pave the way for the establishment of diagnostic methods that are scalable and inexpensive. An important first step would be to test whether the signature can predict TB in the general population, rather than the select populations included in this project,” the investigators added.

This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the European Union, the South African Medical Research Council, and Aeras. Dr. Hanekom and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.