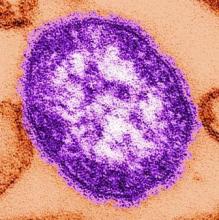

The largest measles outbreak in the United States in more than 2 decades, with an attack rate several orders of magnitude larger than the usual annual nationwide incidence of the disease, could have been better controlled if clinicians had recognized the index cases sooner, according to a report published online Oct. 6 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

At 4 months’ duration, the 2014 measles outbreak in undervaccinated Amish communities across Ohio was also the longest-lasting one on record since the disease was eliminated in the United States, said Paul A. Gastañaduy, MD, of the division of viral diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his associates.

The investigators described the epidemiologic features of the outbreak and containment efforts to limit the spread of the disease.Two index cases developed in young Amish men (aged 22 and 23 years) who had just returned from a church-sponsored trip to the Philippines to perform charitable work among victims of a typhoon. They had not received any guidance about contagious diseases before their trip. Both developed prodromal symptoms (cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis) the day after their return, then a generalized red maculopapular rash 2 days later. They were then admitted to a local hospital and found to have thrombocytopenia and were diagnosed as having dengue fever. Only after a febrile illness with rash developed in 2 more returning relief workers, then in 12 additional contacts within the Amish community, was measles recognized and reported to the health department a full 30 days later. “Health care providers should maintain a high awareness of measles when returning unvaccinated travelers present with a fever and rash,” Dr. Gastañaduy and his associates said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct 6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602295).

A total of 383 people developed measles in this outbreak; 380 were Amish, and the other 3 were epidemiologically linked to the Amish community. The Amish sect doesn’t specifically prohibit vaccination, but immunization rates are low because the people’s personal and cultural beliefs limit participation in preventive health care. The fact that this outbreak was confined almost exclusively to the Amish indicates that high vaccine coverage in the general Ohio population probably prevented further spread of measles, the investigators noted. A total of 52% of the cases occurred among children and adolescents aged 5-17 years and 25% among persons aged 18-39 years.

After the outbreak was recognized, “engagement of local leaders, isolation of infectious persons, quarantine of those exposed, and vaccination of susceptible persons” allowed it to be contained. Local health departments implemented enhanced surveillance and met with community leaders to encourage case reporting, emphasize the importance of vaccination, inform residents about testing, and alert health care providers statewide about the outbreak. A total of 120 free vaccination clinics were held and 10,644 people were immunized.

This study was supported by the Ohio Department of Health and the CDC. Dr. Gastañaduy and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.