Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) with or without azithromycin (AZ) is not associated with a lower risk of requiring mechanical ventilation, according to a retrospective study of Veterans Affairs patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

The study, which was posted on a preprint server April 21 and has not been peer reviewed, also showed an increased risk of death associated with COVID-19 patients treated with HCQ alone.

“These findings highlight the importance of awaiting the results of ongoing prospective, randomized controlled studies before widespread adoption of these drugs,” write Joseph Magagnoli with Dorn Research Institute at the Columbia (S.C.) VA Health Care System and the department of clinical pharmacy & outcomes sciences, University of South Carolina, and colleagues.

A spokesperson with the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, where several of coauthors practice, said that the authors declined to comment for this article before peer review is completed.

The new data are not the first to suggest no benefit with HCQ among patients with COVID-19. A randomized trial showed no benefit and more side effects among 75 patients in China treated with HCQ, compared with 75 who received standard of care alone, according to a preprint posted online April 14.

No benefit in ventilation, death rates

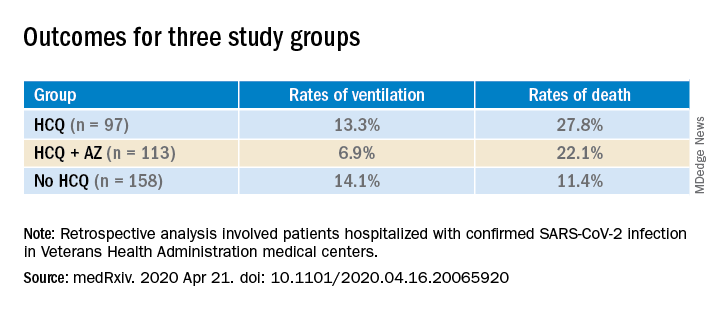

The current analysis included data from all 368 male patients hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19 and treated at Veterans Health Administration medical centers in the United States through April 11.

Patients were categorized into three groups: those treated with HCQ in addition to standard of care (n = 97); those treated with HCQ and the antibiotic azithromycin plus standard of care (n = 113); and those who received standard supportive care only (n = 158).

Compared with the no HCQ group, the risk of death from any cause was higher in the HCQ group (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.61; 95% confidence interval, 1.10-6.17; P = .03) but not in the HCQ+AZ group (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.56-2.32; P = .72).

The risk of ventilation was similar in the HCQ group (aHR, 1.43; 95% CI, 0.53-3.79; P = .48) and in the HCQ+AZ group (aHR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.16-1.12; P = .09), compared with the no-HCQ group.

This study provides another counterbalance to claims of HCQ efficacy, David R. Wessner, PhD, professor of biology and chair of the department of health and human values at Davidson (N.C.) College, said in an interview.

Interest in HCQ spiked after an open-label, nonrandomized, single-center study of COVID-19 patients in France suggested that hydroxychloroquine helped clear the virus and had a potential enhanced effect when combined with azithromycin.

But the 36-patient trial has since been called into question.

Wait for convincing data

Dr. Wessner, whose research focuses on viral pathogenesis, says that, although the current data don’t definitively answer the question of whether HCQ is effective in treating COVID-19, taking a “let’s try it and see” approach is not reasonable.

“Until we have good, prospective randomized trials, it’s hard to know what to make of this. But this is more evidence that there’s not a good reason to use [HCQ],” Dr. Wessner said. He points out that the small randomized trial from China shows that HCQ comes with potential harms.

Anecdotal evidence is often cited by those who promote HCQ as a potential treatment, but “those are one-off examples,” Wessner continued. “That doesn’t really tell us anything.”

Some HCQ proponents have said that trials finding no benefit are flawed in that the drug is given too late. However, Dr. Wessner says, there’s no way to prove or disprove that claim without randomized controlled trials.