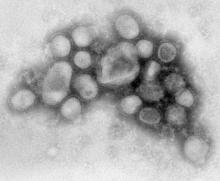

Europe’s top epidemiologists say that they’ve vastly improved their monitoring of emerging disease threats, including obscure ones, such as anthrax and plague. They also acknowledged, however, that the H1N1 pandemic may have resulted in less attention paid to other threats last year.

This week the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control issued a report describing disease outbreaks and threats from 2009 – both within Europe and with the potential to affect Europe -- and assessing its response to each.

During the peak of the H1N1 pandemic in Europe, between April and September 2009, the agency noted a dip in reporting of other threats, particularly the type of food and waterborne diseases that tend to increase in the summer. This suggested that the member states’ attention to H1N1 may have resulted in under-monitoring and under-reporting of these threats to ECDC, according to Dr. Denis Coulombier, the head of the ECDC’s preparedness and response unit in Stockholm.

“It’s very clear that some of the other notifications that we should have received were not coming in,” Dr. Coulombier said in an interview. The dip seemed to be limited to the diarrheal illnesses and not the potentially graver threats on ECDC’s radar that year, such as the ongoing Q fever outbreak in the Netherlands, which saw more than 2,000 cases in 2009. “My main concern was to miss something else because of the pandemic,” Dr. Coulombier said. “Thankfully, I don’t think we missed much.”

The ECDC is a young organization, established in 2005 to increase information sharing among European Union member states and, to some degree, relieve them of their responsibilities in monitoring any global infectious disease threats, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and avian influenza, with the potential to impact Europe. Threats can include anything from a tuberculosis case on a plane to a multi-year threat such as West Nile virus, or even an endemic threat such as Q fever. Like criminal cases, the threats are considered open or closed. The vast majority are open for two weeks or less, while a small number of standing threats, such as avian influenza, remain open over a period of years.

Since instituting centralized monitoring, the agency noted in its report, the number of threats it has watched annually increased from 99 in 2005 (ECDC started monitoring in June of that year) to 251 in 2008. The increase, Dr. Coulombier said, was mainly due to the ECDC’s intelligence work on global threats, while threats reported by the member states remained relatively constant.

But in 2009, the number of threats dropped again —to 192, suggesting that the emergence of pandemic H1N1 may have siphoned off the attentions of the reporting countries and even the agency itself. “Events such as a pandemic require the extensive mobilization of public health resources, which seems to significantly reduce vigilance for other threats,” ECDC noted in its report.

While the most public threat of 2009, pandemic influenza H1N1, gobbled most of the headlines, the agency was also monitoring and helping to investigate outbreaks of Q fever, anthrax, measles, mumps, E. coli in petting zoos, an accidental exposure to Ebola, locally transmitted malaria, and a report of bubonic plague at a terrorist camp in Algeria, later deemed a hoax.

One threat from 2009, detailed in the report, involved a possible deliberate contamination of pool water in Italy. Dr. Coulombier said that the ECDC was “really strengthening the investigation” of cases involving the potential intentional release of pathogens and wants member states to be more vigilant about them. Last year the ECDC investigated a biosafety threat involving Ebola exposure in a lab and dealt with mysterious cases of anthrax among drug users in Scotland, issuing warnings to member states with protocols for handling patients, corpses, and biological or drug samples. The anthrax threat, believed to be linked to contaminated heroin, is considered ongoing.

Cases of Q fever rose from fewer than 20 notified cases annually to 168 in 2007, to 1,007 in 2008. In 2009, cases doubled. All the cases occurred in the Netherlands, and are likely related to goat and sheep farming near densely populated areas, the agency said in its threat report, but the disease has the potential to cross borders.

Dr. Coulombier said that the ECDC is continuing to monitor Q fever intensely, along with a panoply of obscure but real threats: vector-borne diseases such as dengue, malaria, West Nile disease, and Chikungunya fever, all of which occurred both last year and in 2010 in Europe.