Active Phase

After the implementation phase, the next 15 months were dedicated to daily rounding and bedside auditing, the foundation of our project. Rounding was done by the unit manager or nurse champion and involved talking with the bedside nurse and completing the audit tool. These bedside conversations were an opportunity to review the HICPAC guidelines, identify education needs, and reinforce best practices. During these discussions, the nurses often would identify reasons to remove catheters.

The CAUTI team met monthly to review the previous month’s data, other observed opportunities for improvement, and any patient CAUTI information provided by our infection control nurse liaison. We conducted root cause analysis when CAUTIs developed, in which we reviewed the patient’s chart and sought to identify possible interventions that could have reduced the number of catheter days. Our findings were shared in staff meetings, newsletters, and through quality bulletin boards. We also recognized improved performance. Tokens that could be cashed in at the cafeteria for snacks or drinks were awarded to nurses who removed a urinary catheter. We also organized a celebration on the unit the first time we had 3 months without a CAUTI.

Challenges Encountered

Culture change is challenging. The entrenched mindset was that “If a patient is sick enough to be in an ICU, then they are sick enough to need a urinary catheter.” Standard nursing practice typically included placement of a urinary catheter immediately on arrival to the ICU if not already present. Over the years, placing a urinary catheter had become the norm in the ICU, with nurses noting concern about obtaining accurate measurement of urine output and prevention of skin breakdown from incontinence. We had to continually address these concerns to make progress on the project. By providing alternatives to urinary catheters, such as incontinence pads, external male collection devices in varying sizes, moisture barrier products, and scales to measure urine output, nurses were more willing to comply with catheter removal.

We worked with our wound and ostomy nurses to ensure we were providing the proper moisture barrier products and presented research to support that incontinence did not need to lead to pressure ulcers. The wound care team helped with guiding the use of products for incontinent patients to prevent incontinence-associated dermatitis and potential skin breakdown. Our administration financially supported our program, allowing us to bring in and trial supplies. As we identified products for use, we were able to place them into floor stock and make them easily available to nursing. Items such as wicking pads, skin protective creams, and alternatives to catheters were a vital part of our bedside toolkit to maintain our patient’s skin integrity.

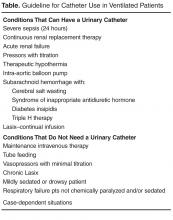

Another expectation within the ICU culture was that all mechanically ventilated patients required a urinary catheter. It was felt that if a patient requires a ventilator in the ICU, then they are “critically ill,” and “critically ill” patients meet HICPAC guidelines for a catheter. However, we learned that this did not always need to be the case as we started to remove catheters on stable ventilated patients. The CAUTI team consequently developed guidelines for the use of catheters in mechanically ventilated ICU patients ( Table