Strategy for Change

We applied the principles of clinical microsystems and conducted numerous tests of change following the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) technique [10,11]. We organized a core team consisting of 6 individuals: our CF center director (pulmonologist); a hospital-employed pediatric endocrinologist; an outpatient CF clinic nurse coordinator; the hospital’s CF coordinator (pediatric nurse practitioner); a hospital-employed, certified diabetes educator (nurse); and the hospital’s CF dietitian. The core team met weekly throughout the year-long project and ensured other CF care providers were kept up-to-date on the changes implemented with the project.

Interventions

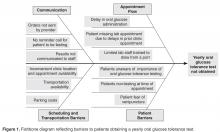

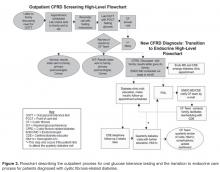

Outpatient Screening

To achieve a thorough understanding of the clinic processes, we informed patients and families of our project and invited them to participate in a phone survey, which consisted of open-ended, scripted questions regarding their experiences with outpatient screening. Topics included scheduling lab appointments, obtaining annual lab work and the methods of communicating lab results. In addition to family surveys, the clinic staff examined each step of the lab scheduling process. The results from the surveys and lab review were used to construct a fishbone diagram ( Figure 1 ) yielding 4 screening barriers: communication, appointment flow, transportation and scheduling, and other patient barriers. These barriers led to a high-level flowchart for outpatient CFRD screening and created a framework to initiate PDSA cycles ( Figure 2 ).The OGTT was added to a previously established protocol for all patients to complete their annual labs at their first visit of the year. We stressed the importance and rationale for the OGTT in an annual clinic letter sent to families. The family was also sent a reminder letter with fasting instructions, a copy of the annual lab orders, and a reminder telephone call before the appointment. Based on family input regarding delays in the turn-around time for venous blood samples, a point of care (POC) glucose protocol was implemented. Laboratory personnel drew annual blood work, completed a POC blood glucose (in addition to the serum glucose), and administered the oral glucose load if the POC glucose was < 200 mg/dL.

Subsequent to completion of our project, we learned that our lab had inadvertently administered a 37.5-g dose for the OGTT instead of the recommended 75-g dose. To identify patients who may have had CFRD but were not diagnosed due to the low oral glucose dose, we have screened all patients with the corrected dose since January 2013.

To improve communication between the pulmonary and endocrine teams, weekly meetings were scheduled. The teams reviewed patients who had recently completed their annual laboratory tests or recently saw an endocrinology provider. After review of lab values, the patient families were mailed letters informing them of their child’s glucose test results which were categorized as normal, impaired, or abnormal suggesting CFRD. If the patient did not complete the OGTT, the family was mailed a letter reiterating the importance of screening. In the event of an abnormal OGTT suggesting CFRD, the results were discussed with the family during a clinic appointment. The endocrinologist and diabetes educator were subsequently notified, and an endocrine clinic appointment was arranged with the family to discuss the results and care plan. An electronic dashboard (spreadsheet) was created to track lab values and clinic visits for patients with impaired blood glucose tolerance as well as CFRD. The dashboard was reviewed and updated on a quarterly basis.