While it is recognized that CDAD carries significant cost burden and is driven by LOS, current literature is lacking regarding the characteristics of these hospital stays. Building on the Quimbo et al study, the current study was designed to probe further into the nature of the burden (ie, resource use) incurred during the course of CDAD hospitalizations. As such, the objective of this study was to identify the common trends in hospital-related resource utilization and describe the potential drivers that affect the cost burden of CDAD using hospital medical record data.

Methods

Population

Patients were selected for this retrospective medical record review from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database (HealthCore, Wilmington, DE). The database contains a broad, clinically rich and geographically diverse spectrum of longitudinal claims information from one of the largest commercially insured populations in the United States, representing 48 million lives. We identified 21,177 adult (≥ 18 years) patients with at least 1 inpatient claim with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code for C. difficile infection (CDI; 008.45) between 1 January 2005 and 31 October 2010 (intake period). All patients had at least 12 months of prior and continuous medical and pharmacy health plan eligibility prior to the incident CDAD-associated hospitalization within the database. Additional details regarding this cohort identification has been published previously [11]. The study was undertaken in accordance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidelines and the necessary central institutional review board approval was obtained prior to medical record identification and abstraction.

Sampling Strategy

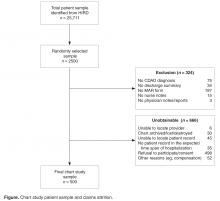

To achieve the target sample of 500 fully abstracted medical records, 2500 patients were randomly selected via systematic random sampling without replacement from the original CDAD population of 21,177; their earliest hospital stay during the intake period with a diagnosis of CDI was identified using medical claims’ data and targeted for medical record abstraction. To be considered eligible for abstraction, medical records were required to include physicians’ and nurses’ notes/reports, discharge summary notes, medication administration record (MAR), and confirmation of CDAD via a documented CDI ICD-9-CM diagnosis or written note by a physician or nurse. Records with invalid or missing hospital or patient names were deemed ineligible for abstraction. Medical record retrieval continued until the requisite 500 CDAD-validated medical records were abstracted ( Figure).Medical Record Abstraction

During the record abstraction process, information was collected on patients’ race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), admission diagnosis and other conditions, point of entry and prior location, body temperature and laboratory data (eg, creatinine and albumin values, white blood cell [WBC] count), diarrhea and stool characteristics, CDAD diagnosis date, CDAD-specific characteristics, severity, complications, and related tests/procedures, CDAD treatments (eg, dose, duration, and formulation of medications), hospital LOS, including stays in the intensive care unit (ICU), cardiac care unit (CCU) following CDAD diagnosis; consultations provided by gastrointestinal, infectious disease, intensivists, or surgery care specialists, and discharge summary on disposition, CDAD status, and medications prescribed. Standardized data collection forms were used by trained nurses or pharmacists to collect information from the medical records and inter-rater reliability testing with a 0.9 cutoff was required to confirm accuracy. To ensure consistency, a pilot test of the first 20 abstracted records were re-abstracted by the research team. Last, quality checks were implemented throughout the abstraction process to identify any inconsistencies or data entry errors including coding errors and atypical, unrealistic data entry patterns (eg, identical values for a particular data field entered on multiple records; implausible or erratic inputs; or a high percentage of missing data points). Missing data were not imputed.