Cytogenetics are also important in predicting response to therapy. For instance, patients with deletion(11q) disease have improved survival when treated with regimens containing an alkylating agent [18]. Deletion(17p) patients respond poorly to traditional cytotoxic agents, and treatments with alternate mechanisms of action should be used [5,19]. The gene for tumor suppressor protein TP53 is encoded in this region of chromosome 17, thus treatment with agents that act independent of pathways involving TP53 are preferred [20].

In addition to cytogenetic testing, quantization of somatic mutations in the gene encoding the variable region of the immune globulin heavy chain gene (IGHV) can help define disease-specific risk. When greater than 98% sequence homology is seen, the gene is considered IGHV unmutated. Patients with an unmutated IGHV have worse overall survival. In one study of Rai stage 0 CLL patients, those with an unmutated IGHV had a survival of only 95 months, compared with 293 months in the mutated group [12].

• When should CLL be treated?

CLL is not curable with current standard therapies, and starting treatment at time of diagnosis for early stage, asymptomatic, CLL patients does not improve overall survival and adds treatment-related toxicities [21,22]. Consequently, the decision to treat is based on treating or preventing complications from the disease, and observation is recommended for most asymptomatic, early-stage patients [6]. Because median survival in CLL is often measured in years, deferring treatment can limit both the short- and long-term complications of therapy, especially the significant risk of secondary malignancies associated with some therapies [23]. However, deferring treatment can significantly impact both a patient’s emotional well-being and quality of life, which should be kept in mind when first discussing the rationale for observation with asymptomatic patients [24].

Treatment is initiated for advanced-stage and/or symptomatic disease. Commonly accepted indications for treatment are listed in Table 4 . Notably, the absolute value of the lymphocyte count is itself not a criterion for treatment. Although many CLL patients may have lymphocyte counts that are quite high (> 500,000), they do not develop the same clinical manifestations of leukostasis observed among patients with acute leukemia [6,25]. Therefore, absent a rapid lymphocyte doubling time or other clinical indications for treatment, lymphocytosis alone should not prompt a decision to treat. The decision to treat based on symptoms alone can be difficult. A reasonable effort should be made to ensure all symptoms are in fact related to CLL and cannot be attributed to othercauses.

For patients with anemia, neutropenia, or thrombocytopenia that is autoimmune in nature, treatment should typically begin with corticosteroids, as it would for non-CLL associated cases of autoimmune cytopenias. If steroids are not effective, second-line treatments appropriate for the situation are generally employed, including intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, azathioprine, and splenectomy. Rituximab has also been shown to be effective in steroid-refractory cases of autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with CLL [26]. Only if cytopenias are refractory to appropriate second-line therapy should CLL-directed treatments be considered, assuming there are no other indications to treat the underlying CLL [6]. Bone marrow biopsy can be helpful in differentiating autoimmune cytopenias from marrow failure due to CLL infiltration.

• What treatments are most appropriate for young, fit patients?

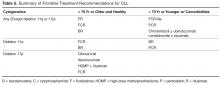

Once the decision to treat is made, therapies are selected to best fit both treatment goals and the patient’s age and underlying comorbidities. There are many effective regimens, and the majority of patients will experience a response to therapy. For purposes of treatment selection, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network clinical practice guidelines divide patients into those younger than 70 and/or older without significant comorbidities, or patients older than 70 and/or younger patients with significant comorbidities. Cytogenetic results are also considered, since patients harboring deletions of chromosomes 17p and 11q require specific management [27]. Table 5 summarizes treatment regimens by patient category.For younger patients who are in good general health, the standard treatment choice is combination chemoimmunotherapy. While single agent therapies can effectively palliate symptoms in most cases, they do not offer a survival benefit. Treatment with chemoimmunotherapy, consisting of cytotoxic chemotherapy given in combination with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (generally rituximab), results in high response rates and conveys an advantage with respect to both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Several chemoimmunotherapy regimens are commonly used.

As compared to fludarabine alone, frontline therapy with the combination of rituximab and fludarabine (FR) results in both a higher overall response rate (84% compared with 63% with fludarabine alone) and more complete responses (38% compared with 20% with fludarabine alone). The probability of PFS at 2 years is also better with FR: 67% compared to 45% with single agent fludarabine [28,29]. Neutropenia is more common with the combination regimen but does not appear to increase the rate of infection. Rituximab infusion reactions are commonly observed, so a stepped-up dosing schedule was developed to decrease their incidence and severity.

Fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) is another highly effective regimen. This combination has similar efficacy to FR with a 90% to 95% overall response rate (ORR) and 44% to 70% complete response (CR) rate [19,30]. Long-term results with this regimen are favorable; 6-year OS of 77% and median time to progression of 80 months have been reported in a follow-up study [31]. However, hematologic toxicity, including severe neutropenia, is common, and many patients are unable to complete all planned therapy [19]. The addition of cyclophosphamide does appear to be especially important for patients with a deletion(11q). Several clinical trials have consistently found that measures of response and survival are improved for deletion(11q) patients receiving an alkylating agent in addition to a nucleoside analogue [18,32,33]. Outcomes in patients with deletion(17p) disease remain poor after FCR; this subset demonstrates the shortest PFS at only 11.5 months [19].

A more recently developed chemoimmunotherapy option for younger, fit patients is bendamustine and rituximab (BR). Bendamustine has structural similarities to both alkylating agents and purine analogues, and is significantly more efficacious than chlorambucil as a single agent [34]. The combination is generally well tolerated, and a phase 2 trial of the combination reported an overall response rate (ORR) of 88.0% [32]. Notably, when the results were examined by genetic risk group, the regimen remained effective for deletion(11q) patients, who achieved overall and CR rates of 90% and 40%, respectively. Unfortunately, only 37.5% of deletion(17p) patients responded, and no patients achieved a CR [32].

The risk for therapy-related neoplasms should be taken into account when selecting initial therapy given the expected long-term survival of most CLL patients. About 8 out of 300 FCR-treated patients developed a therapy-related neoplasm in one study [31]. Treatment with FR, which does not include an alkylating agent, does not appear to have the same risk. In a study reporting long-term follow-up on 104 patients treated with FR, none developed a therapy related neoplasm [35]. Risks associated with bendamustine have not been well characterized but appear to be lower than FC. While inclusion of an alkylating agent is important for deletion(11q) patients, it is not clear if other patients similarly benefit, thus meriting the potentially increased risk for second cancers.

Fortunately, the choice among these similarly effective regimens will soon be based on high-quality, comparative data. FCR and BR have now been directly compared as a first-line treatment in the German CLL Study Group CLL10 trial. At interim analysis, both regimens had the same ORR and 2-year OS. However, CRs were less common in the BR group (38.1% versus 47.4% with FCR) and PFS was likewise inferior. Expectedly, the FCR group experienced more myelotoxicity and infections. The rate of severe neutropenia with FCR was higher at 81.7% compared to only 56.8% with BR [36]. This may be an important consideration when selecting a regimen for individual patients. Baseline renal function may influence choice as well. The active metabolite of fludarabine is eliminated through the kidneys and patients with decreased renal function have been excluded from clinical trials of FCR [19,37]. The phase 2 study of BR included patients with impaired renal function and 35% of participants had a creatinine clearance of less than 70 mL/min. It is notable that increased toxicity was seen in this subset, including higher rates of myelosuppression and infection [32]. As few direct comparisons have been done, the choice between effective first-line chemoimmunotherapy regimens can be difficult. The final results of the CLL 10 trial, as well as the now completed CALGB 10404 trial comparing FCR to FR, will provide new evidence regarding the relative risks and benefits of these regimens, particularly for patients without high-risk chromosomal abnormalities.

• What treatments are most effective for patients with deletion(17p) CLL?

As noted above, deletion(17p) CLL responds poorly to standard treatments. This relative lack of durable response to chemoimmunotherapy appears attributable to loss of function of the tumor suppressor protein TP53 which is encoded in the affected area [20,32,38]. In vivo evidence suggests that fludarabine works through a TP53-dependent mechanism, which likely explains the poor results obtained when deletion(17p) patients are treated with fludarabine-based combinations [38]. Patients harboring deletion(17p) or TP53 mutations should thus be referred for participation in clinical trials or allogeneic stem cell transplantation [17,27].

If initial treatment of a patient with deletion(17p) begins outside of a clinical trial, it should ideally be comprised of agents that have a TP53-independent mechanism of action [20]. Alemtuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the CD52 antigen expressed on the surface of normal and malignant B- and T-lymphocytes, demonstrated ORR of 33% to 50% in studies of patients with relapsed and refractory CLL [39–42]. A retrospective analysis found that similar outcomes were seen in those who had a TP53 mutation or deletion(17p). A subsequent study of previously untreated CLL patients randomized to treatment with 12 weeks of alemtuzumab or chlorambucil found that alemtuzumab-treated deletion(17p) patients had an ORR of 64% and median PFS of 10.7 months [43]. Alemtuzumab is therefore a rational choice for first-line therapy in this population. Hematologic toxicity is frequent, however, and all patients must receive prophylaxis against and monitoring for reactivation of CMV infection [43]. Infusion reactions are common but may be reduced by subcutaneous administration without apparent loss of efficacy [42,44]. While alemtuzumab is no longer marketed in the United States for the indication of CLL, it is available free of charge from the manufacturer [45].

High-dose methylprednisolone with rituximab (HDMP-R) has also been successfully used as both salvage and first-line therapy in this group. As salvage therapy, responses were seen in greater than 90% of patients, including over 50% of deletion(17p) patients [46-48]. In treatment-naïve CLL, the ORR was 96% [49], although data for patients with deletion 17p is limited in the frontline setting. Myelotoxicity attributable to the regimen is modest, but good antimicrobial prophylaxis is warranted, as well as close monitoring for hyperglycemia in at-risk patients.

• How is treatment modified for older or less fit patients?

For patients older than 70, or those who have significant comorbidities, effective therapies are still available. As most new diagnoses of CLL are made in patients older than 65, age is but one important factor determining an individual patient’s ability to tolerate treatment. The German CLL Study Group has usefully classified elderly patients into 3 treatment groups based on fitness and goals of care. The first group of medically fit patients with a normal life expectancy, sometimes referred to as the “go go” group, generally tolerate standard chemoimmunotherapy. A second group of older patients with significant life-limiting comorbid conditions—the so-called “no go” patients —should be offered best supportive care rather than CLL-directed treatment. A third group of “slow go” patients falls in between these two; these patients have comorbidities with variable life expectancy and will likely tolerate and benefit from CLL-directed therapy [50].

While some older patients can safely receive chemoimmunotherapy at standard doses and schedules, FCR can prove intolerable for even the medically fit elderly. Because inferior outcomes have been reported among patients older than 70 [30,31], a reduced-dose FCR regimen (FCR-lite) has been studied. Doses of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide were reduced by 20% and 40% respectively and dosing frequency of rituximab was increased. The CR rate was favorable at 77%, the rate of severe neutropenia was reduced to only 13%, and most patients completed all planned therapy [51]. Alternatively, the combination of pentostatin, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (PCR) has also been successfully used in older patients. The overall and CR rates, 91% and 63% respectively, were durable at 26 months of follow-up. Importantly, there was no statistically significant difference in response or toxicity among the 28% of patients older than 70 [52,53].

For less fit patients, chlorambucil remains a reasonable option. Chlorambucil, a well-tolerated oral alkylating agent, has been used as a frontline therapy in CLL for decades. Chlorambucil has demonstrated consistent response rates in at least 4 clinical trials and is an appropriate option for patients who cannot tolerate more intensive therapy [54]. When a multicenter phase III trial compared it directly to fludarabine in patients over 65, the PFS and OS were no different despite favorable response rates in fludarabine-treated patients [55]. The effectiveness of single-agent chlorambucil can be improved, and the tolerability maintained, with the addition of a CD20-directed monoclonal antibody [56]. Obinutuzumab, a glycolengineered type II antibody against CD20, has recently been shown to improve treatment efficacy when used in combination with chlorambucil [57]. The CLL11 trial randomized patients with comorbid conditions to 1 of 3 treatments: single-agent chlorambucil, chlorambucil with rituximab (R-Clb), or chlorambucil with obinutuzumab (G-Clb). Both chemoimmunotherapy combinations outperformed chlorambucil alone, but the inclusion of obinutuzumab was associated with higher CR rates and longer PFS than rituximab, although infusion reactions and neutropenia were more common in the obinutuzumab arm [57]. Based on this result, the US Food and Drug Administration has now approved obinutuzumab for use in combination with chlorambucil as frontline therapy. While regulatory approval is without restriction with respect to patient age or fitness, a chlorambucil backbone remains most appropriate for older patients and/or those with significant comorbidities.

• What therapies are currently under development?

Numerous targeted treatments and novel immunotherapies are under active investigation in CLL. With greater specificity for CLL, these emerging agents offer the possibility of more effective yet less toxic treatments that will undoubtedly change the landscape for future CLL therapy. These agents are currently most studied as salvage therapies, and given their targeted mechanism of action can be highly effective in relapsed and refractory patients who frequently harbor poor risk cytogenetic abnormalities such as deletion(17p). Data for these agents as initial treatment is limited. Ongoing clinical trials employing these newer agents will need to be reported before these drugs can be recommended as frontline therapies.

Frontline experience with the oral immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide is more extensive. Lenalidomide offers convenient daily dosing and a favorable toxicity profile. When given on a continuous dosing schedule to patients who were 65 years old or older, the ORR was 65%, and 88% of patients were still alive at 2 years’ follow-up. The quality of response continued to improve beyond 18 months of treatment. Neutropenia, the most common severe toxicity, complicated about a third of cycles. Tumor flare attributable to immune activation was also seen, but in most cases was low-grade and did not require intervention [58,59]. While life-threatening tumor lysis syndrome and tumor flare have been seen with lenalidomide in CLL, such concerns are largely abrogated by a lower starting dose and careful intrapatient dose titration [60]. Lenalidomide has also been combined with rituximab and yielded promising results. Sixty-nine treatment-naïve patients were treated with escalating doses of lenalidomide along with rituximab infusions starting at the end of cycle 1 in a phase 2 study. They achieved an 88% ORR with 16% CRs. Toxicities were generally manageable, but patients over 65 were less likely to reach higher doses of lenalidomide or complete all planned treatment cycles [61]. Unfortunately, the FDA recently halted accrual to a phase 3 frontline clinical trial comparing lenalidomide to chlorambucil due to excess mortality in the lenalidomide arm among patients over the age of 80 [62]. More detailed outcomes from that study should be forthcoming.

Perhaps the most remarkable recent advance in CLL medicine, however, is the advent of orally bioavailable small molecule inhibitors of the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway. BCR signaling plays a vitally important role in supporting the growth and survival of malignant B-cells, activating a number of downstream kinases (Syk, Btk, PI3K, among others) which are potential therapeutic targets. Proof of principle for this approach was demonstrated with the Syk inhibitor fostamatinib in a phase 1/2 trial enrolling patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL. CLL/SLL patients had the highest response rates of any subgroup in that study, with 6 out of 11 patients responding [63]. In a subsequent phase 1b study of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib, durable partial remissions were reported in more than 70% of multiply relapsed and refractory patients, including genetically high-risk patients [64–66]. Ibrutinib appears safer and better tolerated than traditional chemoimmunotherapy in the relapsed setting; consequently, it is now being studied as a first-line therapy both alone and in combination with other agents [67]. Other BCR signaling agents under study, such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor idelalisib, demonstrate similar safety and high response rates across both genetic risk and patient age groups [68].

New targeted drugs are not limited to the BCR signaling pathway. ABT-199 inhibits B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), which is an anti-apoptotic protein in the cell death pathway, and has demonstrated remarkable clinical efficacy in relapsed and refractory CLL patients [69]. As more experience is gained with these targeted agents, it is expected that they will be rapidly incorporated into frontline therapies. However, these agents are just now being studied in comparison to standard initial treatments, such as FCR, and it is not yet clear they will offer an advantage over current chemoimmunotherapy in this setting [70–72]. Since these single agents typically do not induce complete remissions, and require indefinite therapy to maintain response, optimal combination therapies are under intensive investigation.

Case Conclusion

The patient and his physician elect to begin treatment owing to symptomatic cervical lymphadenopathy and massive splenomegaly. Given the presence of a deletion(11q) abnormality, but hoping to limit the risk for both short- and long-term toxicities, this younger, fit patient is treated with 6 cycles of bendamustine and rituximab. At the conclusion of treatment, neither the cervical lymph nodes nor spleen remain palpable. His blood counts have also normalized, with a white blood cell count of 4700 with 8.1% lymphocyotes, hemoglobin of 14.3 gm/dL, and platelets of 151,000/dL.

Summary

CLL follows a chronic course requiring treatment at variable intervals. Both genetic risk features and patient factors should be considered when determining initial therapy. Cytogenetic and molecular testing can characterize the likelihood of treatment success, information useful for treatment planning. Chemoimmunotherapy is highly effective for most patients, including patients with deletion(11q) CLL, where the inclusion of an alkylating agent in frontline therapy alters the natural history of disease. However, patients with deletion(17p) and or TP53-mutated disease respond poorly to standard treatment and should be considered for investigational therapies [73]. Novel approaches to CLL therapy, most notably immunotherapies and BCR-targeted agents, hold the promise to further improve outcomes, particularly for the highest risk patients and those elderly and/or infirm patients who tolerate chemotherapy poorly. Frontline therapy should rapidly evolve as emerging agents enter advanced phase investigation.

Corresponding author: Jeffrey Jones, MD, MPH, Div. of Hematology, Ohio State University, A350B Starling Loving Hall, 320 West 10th Ave., Columbus, OH 43210, jeffrey.jones@osumc.edu.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Jones disclosed that he is on the advisory boards and has received research support from Genentech, Pharmacyclics, and Gilead.

Author contributions: conception and design, KAR, JAJ; analysis and interpretation of data, KAR, JAJ; drafting of article, KAR, JAJ; critical revision of the article, KAR, JAJ.