Abstract

- Objective: To describe the highlights of our medical center’s implementation of the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s ABCDEF bundle in 3 medical intensive care units (ICUs).

- Methods: After a review of our current clinical practices and written clinical guidelines, we evaluated deficiencies in clinical care and employed a variety of educational and clinical change interventions for each element of the bundle. We utilized an interdisciplinary team approach to facilitate the change process.

- Results: As a result of our efforts, improvement in the accuracy of assessments of pain, agitation, and delir-ium across all clinical disciplines and improved adherence to clinical practice guidelines, protocols, and instruments for all bundle elements was seen. These changes have been sustained following completion of the data collection phase of the project.

- Conclusion: ICU care is a team effort. As a result of participation in this initiative, there has been an increased awareness of the bundle elements, improved collaboration among team members, and increased patient and family communication.

Key words: intensive care; delirium; sedation; mobility.

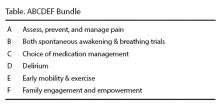

Admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) is a stressful and challenging time for patients and their families. In addition, significant negative sequelae following an ICU stay have been reported in the literature, including such post-ICU complications as post-traumatic stress disorder [1–9], depression [10,11], ICU-acquired weakness [12–19], and post-intensive care syndrome [20–23]. Pain, anxiety, and delirium all contribute to patient distress and agitation, and the prevention or treatment of pain, anxiety, and delirium in the ICU is an important goal. The Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) developed the ABCDEF bundle (Table) to facilitate implementation of their 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium (PAD) [24]. The bundle emphasizes an integrated approach to assessing, treating and preventing significant pain, over or undersedation, and delirium in critically ill patients.

In 2015, SCCM began the ICU Liberation Collaborative, a clinical care collaborative designed to implement the ABCDEF bundle through team-based care at hospitals and health systems across the country. The Liberation Collaborative’s intent was to “liberate” patients from iatrogenic aspects of care [25]. Our medical center participated in the collaborative. In this article, we describe the highlights of our medical center’s implementation of the ABCDEF bundle in 3 medical ICUs.

Settings

The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center is a 1000+–bed academic medical center located in Columbus, Ohio, containing more than 180 ICU beds. These ICU beds provide care to patients with medical, surgical, burn, trauma, oncology, and transplantation needs. The care of the critically ill patient is central to the organization’s mission “to improve people’s lives through innovation in research, education and patient care.”

The medical center has 3 medical ICUs (MICUs) in 3 different physical locations, but they have the same nursing and physician leadership. Two of the MICU units have an interdisciplinary team that includes physicians (attending and fellow) along with advanced practice nurses as patient care providers. One of the MICUs provides the traditional medical model and does not utilize advanced practice nurses as providers. The guidelines and standards of care for all health care team members are standardized across the 3 MICU locations with one quality committee to provide oversight.At the start of our colloborative participation, all of the ABCDEF bundle elements were protocolized in these ICUs. However, there was a lack of knowledge of the content of the bundle elements and corresponding guidelines among all members of our interdisciplinary teams, and our written protocols and guidelines supporting many of the bundle elements had inconsistent application across the 3 clinical settings.

We convened an ABCDEF bundle/ICU liberation team consisting of an interdisciplinary group of clinicians. The team leader was a critical care clinical nurse specialist. The project required outcome and demographic data collection for all patients in the collaborative as well as concurrent (daily) data collection on each bundle element. The clinical pharmacists who work in the MICUs and are part of daily interdisciplinary rounds collected the daily bundle element data while the patient demographic and outcome data were collected by the clinical nurse specialist, nurse practitioner, and clinical quality manager. Oversight and accountability for the ABCDEF bundle/ICU liberation project was provided by an interdisciplinary critical care quality committee. Our ABCDEF bundle/ICU liberation team met weekly to discuss progress of the initiative and provided monthly updates to the larger quality committee.

Impacting the Bundle—Nursing Assessments

The PAD guidelines recommend the routine assessment of pain, agitation, and delirium in ICU patients. For pain, they recommend the use of patient self-report or the use of a behavioral pain scale as the most valid and reliable method for completing this assessment [24]. Our medical center had chosen to use the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT), a valid and reliable pain scale, for assessment of pain in patients who are unable to communicate [26], which had been in use in the clinical setting for over a year when this project began. For agitation, the PAD guidelines recommended assessment of the adequacy and depth of sedation using the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) or Sedation Agitation Scale (SAS) [24] for all ICU patients. Our medical center has chosen to use the RASS as our delirium assessment. The RASS had been in use in the clinical setting for approximately 10 years when this project started. For delirium assessment, the Confusion Assessment Method for ICU (CAM-ICU) [27] or the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) [28] is recommended. Our medical center used the CAM-ICU, which had been in place for approximately 10 years prior to the start of this project. Even though the assessment tools were in place in our MICU unit and hospital-based policies and guidelines, the accuracy of the assessments for PAD was questioned by many clinicians.

To improve the accuracy of our nursing assessments for PAD, a group of clinical nurse specialists and nursing educators developed an education and competency program for all critical care nursing staff. This education program focused on the PAD guidelines and our medical center’s chosen assessment tools. Education included in-person continuing education lectures, online modules, demonstrations, and practice in the clinical setting. After several months of education and practice, all staff registered nurses (RNs) had to demonstrate PAD assessment competency on a live person. We used standardized patients who followed written scenarios for all of the testing. The RN was given 1 of 8 scenarios and was charged with completing a PAD assessment on the standardized patient. RNs who did not pass had to review the education materials and re-test at a later date. More than 600 RNs completed the PAD competency. After completion of the PAD competency, the clinical nurse specialists observed clinical practice and audited nursing documentation. The accuracy of assessments for PAD had increased. Anecdotally, many our critical care clinicians acknowledged that they had increased confidence in the accuracy of the PAD assessments. There was increased agreement between the results of the assessments performed by all members of the interdisciplinary team.

Impacting the Bundle—Standardized Nurse Early Report Facilitation

Communication among the members of the interdisciplinary team is essential in caring for critically ill patients. One of the ways that the members of the interdisciplinary team communicate is through daily patient rounds. Our ABCDEF bundle/ICU liberation team members attend and participate in daily patient rounds in our 3 MICUs on a regular basis. The ABCDEF bundle/ICU liberation team members wanted to improve communication during patient rounds for all elements of the bundle.

Nurse Early Report Facilitation was a standard that was implemented approximately 5 years prior to the start of the ICU Liberation Collaborative. Nurse early report facilitation requires that the bedside staff RN starts the daily patient rounds discussion on each of his/her patients. The report given by the bedside RN was designed to last 60 to 90 seconds and provide dynamic information on the patient’s condition. Requiring the bedside RN to start the patient rounding provides the following benefits: requires bedside RN presence, provides up-to-the-minute information, increases bedside RN engagement in the patient’s plan of care, and allows for questions and answers. Compliance from the bedside RNs with this process of beginning patient rounds was very high; however, the information that was shared when the bedside RN began rounds was variable. Some bedside RNs provided a lengthy report on the patient while others provided 1 or 2 words.

The ABCDEF bundle/ICU liberation team members thought that a way to hardwire the ABCDEF bundle elements would be to add structure to the nurse early report. By using the ABCDEF elements as a guide, the ABCDEF bundle/ICU liberation team members developed the Structured Nurse Early Report Facilitation in which the bedside RN provides the following information at the beginning of each patient discussion during rounds: name of patient, overnight events (travels, clinical changes, etc.), pain (pain score and PRN use), agitation (RASS and PRN use), delirium (results of CAM-ICU). When the bedside RN performs the nurse early report using the structured format, the team is primed to discuss the A, B, C, and D elements of the bundle.

To implement the Structured Nurse Early Report Facilitation in the MICUs, the critical care clinical nurse specialists provided in-person education at the monthly staff meetings. They also sent emails, developed education bulletin boards, made reminder cards that were placed on the in-room computers, and distributed “badge buddy” reminder cards that fit on the RNs’ hospital ID badges. We provided emails and in-person education to our physician and nurse practitioner teams so they were aware of the changes. Our physician and nurse practitioners were encouraged to ask for information about any elements missing from the Structured Nurse Early Report in the early days of the process change.

After a few months, the critical care clinical nurse specialists reported that the Structured Nurse Early Report Facilitation was occurring for more than 80% of MICU patients. Besides the increase in information related to pain, agitation, and delirium, the Structured Nurse Early Report Facilitation increased the interdisciplinary team’s use of the term “delirium.” Prior to the structured nurse early report, most of the interdisciplinary team members were not naming delirium as a diagnosis for our MICU patients and used terms such as ICU psychosis, confused, and disoriented to describe the mental status of patients with delirium. As a result of this lack of naming, there may have been a lack of recognition of delirium. Using the word “delirium” has increased our interdisciplinary team’s awareness of this diagnosis and has increased the treatment of delirium in patients who have the diagnosis.

In addition to improved assessment and diagnosis, the clinical pharmacist began leading the discussions around choice of sedation during daily rounds. Team members began to discuss the patient’s sedation level, sedation goals, and develop a plan for each patient. This discussion included input from all members of the interdisciplinary team and allowed for a comprehensive patient-specific plan to be formed during the daily patient rounds episode.

Impacting the Bundle—Focus on Mobility

There have been many articles published in the critical care literature on the topic of mobility in the ICU. The evidence shows that early mobilization and rehabilitation of patients in ICUs is safe and may improve physical function, and reduce the duration of delirium, mechanical ventilation, and ICU length of stay [29–31]. Our institution had developed a critical care mobility guideline in 2008 for staff RNs to follow in determining the level of mobility that the patient required during the shift. Over the years, the mobility guideline was used less and less. As other tasks and interventions became a priority, mobility became an intervention that was completed for very few patients.

Our ABCDEF bundle/ICU liberation team determined that increasing mobility of our MICU patients needed to be a plan of care priority. We organized an interdisciplinary team to discuss the issues and barriers to mobility for our MICU patients. The interdisciplinary mobility team had representatives from medicine, nursing, respiratory therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy. Initially, this team sent a survey to all disciplines who provided care for the patients in the MICU. Data from this survey was analyzed by the team to determine next steps.

Despite the fact that there were responses from 6 unique disciplines, several common barriers emerged. The largest barrier to overcome was staffing/time for mobility. It was clear from the survey respondents that all health care team members were busy providing patient care. Any change in the mobility guideline or practice needed to make efficient use of the practitioner’s time. Other barriers included space/equipment, communication, patient schedules, knowledge, patient and staff safety, and unit culture. The interdisciplinary mobility team divided into smaller workgroups to tackle the issues and barriers.

Mobility Rounds

Mobility rounds were implemented to attempt to decrease the barriers of time, communication, and know-ledge. Mobility rounds were designed as a start to the shift discussion on the topic of mobility. Mobility rounds included a clinical nurse specialist, a physical therapist (PT), an occupational therapist (OT), and a pulmonary physician/ nurse practitioner. This team met at 7:30 each weekday morning and walked room-to-room through our MICUs. The mobility rounds team laid eyes on each patient, developed a mobility plan for the day, and communicated this plan with the staff RN assigned to the patient. Mobility rounds were completed on all 48 MICU patients in 30 minutes.

Having the mobility rounds team at each patient’s bedside was important in several ways. First, it allowed the team members to see each patient, which gave the patient an opportunity to be part of his/her mobility plan. Also, the staff RNs and respiratory therapists (RTs) were often in the patient’s room. This improved communication as the staff RNs and RTs discussed the mobility plan with the PT and OT. For patients who required many resources for a mobility session, the morning bedside meeting allowed RNs, RTs, PTs, OTs, and physicians to set a schedule for the day’s mobility session. Having a scheduled time for mobility increased staff and patient communication. Also, it allowed all of the team members to adjust their workloads to be present for a complex mobility session.

Another benefit of mobility rounds was the opportunity for the PT and OT team members to provide education to their nursing and physician colleagues. Many nursing and physician providers do not understand the intricacies of physical and occupational therapy practice. This daily dialogue provided the PT/OT a forum to explain which patients would benefit from PT/OT services and which would not. It allowed the RNs and physicians to hear the type of therapy provided on past sessions. It allowed the PT/OT to discuss and evaluate the appropriateness of each patient consult. It allowed the RN and physician to communicate which patients they felt were highest priority for therapy for that day. Mobility rounds are ongoing. Data are being collected to determine the impact of mobility rounds on the intensity of mobility for our MICU patients.

Nurse-Driven Mobility Guideline

Another subgroup revised the outdated critical care mobility guideline and developed the new “Nurse-Driven Critical Care Mobility Guideline.” The guideline has been approved through all of the medical center quality committees and is in the final copyright and publication stages, with implementation training to begin in the fall. The updated guideline is in an easy-to-read flowchart format and provides the staff RN with a pathway to follow to determine if mobility is safe for the patient. After determining safety, the staff RN uses the guideline to determine and perform the patient’s correct mobility interventions for his/her shift. The guideline has built in consultation points with the provider team and the therapy experts.

Other Mobility Issues

A third subgroup from the interdisciplinary mobility team has been working on the equipment and space barriers. This subgroup is evaluating equipment such as bedside chairs, specialty beds, and assistive devices. Many of our MICU patient rooms have overhead lifts built into the ceilings. This equipment is available to all staff at all times. The equipment/space subgroup made sure that there were slings for use with the overhead lifts in all of the MICU equipment rooms. They provided staff education on proper use of the overhead lifts. They worked with the financial department and MICU nurse managers to purchase 2 bariatric chairs for patient use in the MICU.

A fourth subgroup has been working on the electronic documentation system. They are partnering with members of the information technology department to update the nursing and provider documentation regarding mobility. They have also worked on updating and elaborating on the electronic activity orders for our MICU patients. There have been many changes to various patient order sets to clarify mobility and activity restrictions. The admission order set for our MICU patients has an activity order that allows our staff RNs to fully utilize the new nurse-driven critical care mobility guideline.

Impacting the Bundle—Family Engagement and Empowerment

Family support is important for all hospitalized patients but is crucial for ICU patients. The medical center implemented an open visitation policy for all ICUs in 2015. Despite open visitation, the communication between patients, families, and interdisciplinary ICU teams was deficient. Families spoke to many different team members and had difficulty remembering all of the information that they received.

To increase family participation in the care of the MICU patient, we invited family members to participate in daily rounds. The families were invited to listen and encouraged to ask questions. During daily rounds, there is a time when all care providers stop talking and allow family members to inquire about the proposed plan of care for their family member. For family members who cannot attend daily rounds, our ICU teams arrange daily in-person or telephone meetings to discuss the patient’s plan of care. RNs provide a daily telefamily call to update the designated family member on the patient’s status, answer questions, and provide support.

In addition to the medical support for families, there is an art therapy program integrated into the ICU to assist families while they are in the medical center. This program is run by a certified art therapist who holds art therapy classes 2 afternoons a week. This provides family members with respite time during long hospital days. There are also nondenominational services offered multiple times during the week and a respite area is located in the lobby of the medical center.

In addition to these programs, the medical center added full-time social workers to be available 24 hours a day/ 7 days a week. The social worker can provide social support for our patients and families as well as help facilitate accommodations for those who travel a far distance. The social worker plays in integral part on the ICU team, often bridging the gap for families that can be overlooked by the medical team.

Conclusion

Care of the ICU patient is complex. Too often we work in our silos of responsibility with our list of tasks for the day. Participating in the ABCDEF bundle/ICU Liberation Collaborative required us to work together as a team. We were able to have candid conversations that improved our understanding of other team members’ perspectives, helping us to reflect on our behaviors and overcome barriers to improving patient care.

Even though the ICU Liberation Collaborative has ended, our work at the medical center continues. We are in the process of evaluating all of the interventions, processes, and guideline updates that our ABCEDF bundle/ICU liberation team worked on during our 18-month program. There have been many improvements such as increased accuracy of pain and delirium assessments, along with improved treatment of pain in the MICU patient. We have noticed increased communication with the patient and family and among all of the members of the interdisciplinary team. We have changed our language to accurately reflect the patient’s sedation level by using the correct RASS score and delirium status by using the term “delirium” when this condition exists. There is increased collaboration among team members in the area of mobility. More patients are out of bed on bedside chairs and more patients are walking in the halls. Over the next several months our ABCEDF bundle/ICU liberation team will continue to review and analyze the data that we collected in the collaborative. We will use that data and the clinical changes we see on a daily basis to continue to improve the care for our MICU patients.

Corresponding author: Michele L. Weber, DNP, RN, CCRN, CCNS, AOCNS, OCN, ANP-BC, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, 410 West 10th Ave., Columbus, OH 43210, Michele.weber@osumc.edu.