From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To elicit patient perceptions of a computer tablet (“e-Board”) used to display information relevant to hospital discharge and to gather patients’ expectations and perceptions regarding hospital discharge.

- Methods: Adult patients discharged from 1 of 3 medical-surgical, noncardiac monitored units of a 1265-bed, academic, tertiary care hospital were interviewed during patient focus groups. Reviewer pairs performed qualitative analysis of focus group transcripts and identified key themes, which were grouped into categories.

- Results: Patients felt a novel e-Board could help with the discharge process. They identified coordination of discharge, communication about discharge, ramifications of unexpected admissions, and interpersonal interactions during admission as the most significant issues around discharge.

- Conclusions: Focus groups elicit actionable information from patients about hospital discharge. Using this information, e-tools may help to design a patient-centered discharge process.

Key words: hospitals; patient satisfaction; focus groups; acute inpatient care.

Transition from the hospital to home represents a critical time for patients after acute illness, and support of patients and their care partners can help decrease consequences of poor care transitions, such as readmissions [1]. Focused discharge planning may improve outcomes and increase patient satisfaction [2], which is a key metric in hospital value-based purchasing programs, which tie Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Services (HCAHPS) survey scores to reimbursement. Although patient experience surveys explore several categories of patient satisfaction, HCAHPS may not reveal readily actionable opportunities that would allow clinicians to improve patient experience. Conducting focus groups and interviews can help discern patients’ perceptions and provide patient-centered opportunities to improve hospital discharge processes. Recent studies using these methodologies have revealed patients’ perceptions of barriers to inter-professional collaboration during discharge [3] and their desires and expectations of, as well as suggestions for improvement of, hospitalization [4].

Care transition bundles have been developed to facilitate the process of transitioning home [1,5], but none include e-health tools to help facilitate the discharge process. A study group leveraged available software at our institution to create a bedside “e-Board,” addressing opportunities that surfaced during previous patient focus groups regarding our institution’s discharge process. The software tools were loaded onto a tablet computer (Apple iPad; Cupertino, CA) and included displays of the patient’s physician and nurse, with estimated time of team bedside rounds; day and time of anticipated discharge; display of discharge medications; and a screening tool, I-MOVE, to assess mobility prior to return to independent living [6].

We conducted focus groups to gather patients’ insights for incorporation into a bedside e-health tool for discharge and into our hospital’s current discharge process. The primary objective of the current study was to elicit patient and family perceptions of a bedside e-Board, created to display information regarding discharge. Our secondary objective was to learn about patient expectations and perceptions regarding the hospital discharge process.

Methods

Setting

The study setting was 3 medical-surgical, non-cardiac monitored units of a 1265-bed, academic, tertiary care hospital in Rochester, MN. The study was considered a minimal risk study by the center’s institutional review board.

Participants

Patients aged 18 years or older discharged from 1 of the 3 study units during 2012–2013 were eligible to participate. Patients were excluded if they were not discharged home or to assisted living, were clinic employees, retirees or dependents of clinic employees, were hospitalized longer than 6 months prior to study entry, lived further than 60 miles from the town of Rochester, could not travel, or did not sign research consent.

There were 975 patients who met inclusion criteria. The institution’s survey research center randomly selected 300 eligible patients and contacted them by letter after discharge. The letter was followed up with a telephone call and verbal consent was obtained if the patient expressed interest in participation. Of the 17 patients who gave consent, 12 patients participated in focus group interviews.

E-Board Development

Prior focus group discussions facilitated by our institution’s marketing department (Mr. Kent Seltman, personal communication) explored patients’ perceptions of the discharge process from the institution’s primary hospital. The opportunities for improvement that surfaced during these focus groups included identifying the date of discharge, communication about the time of discharge, and discharging the patient at the identified time, not several hours later. The study group leveraged software available at our institution to create a bedside e-Board that could possibly mitigate these issues by improving communication about discharge. The software tools were loaded onto a tablet computer for patients to use as a resource during their admission. These tools included:

- A photo display of the patient’s nurse and physician, with estimated time of bedside rounds

- A display of the day and time of anticipated discharge. Providing anticipated day and time of discharge has been found to be an achievable goal for internal medicine and surgical services [7].

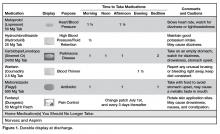

- A medication display, named the “Durable Display at Discharge,” previously found to improve patient understanding of prescribed medications [8]

- A display of a mobility tool, I-MOVE, designed to screen for debility that could prevent patients’ return to independent living [6].

Focus Groups

Facilitated interviews were conducted on 2 consecutive days in March 2014. Participants were divided into a focus group of 5 to 6 participants if they were functionally independent, or dyads of patient and care partner if they were functionally dependent. Interviews were both video- and audiotaped.

A trained facilitator led 1.5-hour sessions with each focus group. The sessions began with introductions and guidelines by which the focus groups were conducted, including explanations of the video and audio recording equipment, and a request for participants to speak one person at a time to facilitate recording. Discussions were carried out in 2 parts, guided by a facilitator script ( available from the authors). First, participants were asked to share their experiences regarding planning for discharge and the information they received leading up to their planned day and time of hospital discharge. Second, participants were shown a prototype of the e-Board. Participants were asked to reflect as to whether they had received similar information when they had been hospitalized, whether that information was helpful or useful, what information they did not receive that would have been helpful, how information was given, and whether information displayed via an e-Board would be better or worse than the ways they received information while in the hospital.

Data Analysis

Three teams, each comprised of 2 reviewers, met to analyze the video and audio recordings of each focus group. Unfortunately, the video files from the dyad interviews were not recoverable after the recorded sessions, and thus those groups were excluded from the study. Reviewers met prior to analyzing the focus group video and audio recordings to review the qualitative analysis protocol developed by the research team [9] (protocol available froom the authors). The teams then independently reviewed the video recordings and transcripts of the focus groups. The reviewer teams observed the focus group recordings and identified (1) themes regarding perceptions of the bedside e-Board and (2) experiences and perceptions around discharge. The protocol helped reviewer teams create a classification structure by identifying the key themes, which were then combined to create categories. The reviewer teams then compared their classification structures and by incorporating the most frequently identified categories, built a relational model of discharge perceptions.

Results

Eleven patients participated in 2 focus groups, one group of 5 patients and the other of 6 patients. Patient participants included 6 females and 5 males ranging in age from 22 to 84 years.

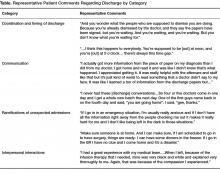

Using the qualitative analysis protocol, review teams grouped key themes from the focus group discussions about discharge into 4 categories. The categories, with themes listed below and representative patient comments in the Table, were

- Coordination and timing of discharge

- Giving patients the opportunity to prepare for discussion with clinician teams

- Communicating the specific time of discharge

- Internal collaboration of inter-professional teams

- Preparing for transition out of the hospital

2. Communication

- Patient inclusion in care discussions

- Discharge summary delay and/or completeness

- Education at the time of discharge

3. Ramifications of the unexpected and unknown

- Increased stress and frustration due to inability to plan, fear of the unknown, and lack of information

4. Interpersonal interactions

- Both favorable and unfavorable interactions caused an emotional response that impacts perceptions of hospitalization and discharge

The reviewers also analyzed patients’ comments regarding the bedside e-Board. The medication display (“Durable Display at Discharge,” Figure 1) was universally considered to be the most relevant and best-liked of the 4 elements tested. The visual display of medications and their purpose were commonly referenced as the most positive aspects of the display, and patients and caregivers were readily able to generate multiple potential uses for the display. Several mentioned that the information on the medication display were so desirable and necessary that if not supplied by the hospital, they hand-crafted such reminder displays at home.

The display of the care team and rounding time was perceived as helpful in allowing patients and family members to coordinate schedules with family members or care partners who may wish to be present during rounds. Patients also favorably reviewed the discharge day and time display, although multiple comments were made that this information is only helpful if it is accurate. Discussion around discharge time evoked the most emotions of topics discussed and patients expressed frustration with the inaccuracy of discharge time communicated to them on the day of discharge. Elaborating on this sentiment, a patient specified, “I prefer they don’t tell me a time at all until they know for sure”, and another shared that, “there is only going to be frustration with that if you say 4 pm and it ends up being 7 pm.”

It was difficult for patients to see how the I-MOVE assessment (Figure 2) would apply to their discharge planning. They perceived I-MOVE as a tool for clinicians. One exception was a patient who had on a previous admission undergone heart surgery. She explained to the other patients that in such debilitated conditions, mobility independence assessments were important and commonly done.

Patients voiced some skepticism and concerns regarding the e-Board, including expense, privacy, security, and cleanliness. One patient observed the tablet was “more current than a printed piece of paper. It’s more up to date.” Other patients, however, questioned the process required to update information and wondered how much electronic displays added compared to the dry-erase board already in each patient’s room with which they were more familiar. They also voiced concern that the tablet would replace face-to-face interactions with their care teams. A patient shared that, “if we don’t have the conversation and we just get it through this, then I would hate that…you want to be able to give your input.”