From the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson, Tucson, AZ.

Abstract

- Objective: To determine predictors of quality and safety of machine translation (Google Translate) of patient care instructions (PCIs), and to determine if machine back translation is useful in quality assessment.

- Methods: 100 sample English PCIs were contributed by 88 clinical faculty. Each example PCI was up to 3 sentences of typical patient instruction that might be included in an after visit summary. Google Translate was used to first translate the English to Spanish, then back to English. A panel of 6 English/Spanish translators assessed the Spanish translations for safety and quality. A panel of 6 English-speaking health care workers assessed the back translation. A 5-point scale was used to assess quality. Safety was assessed as safe or unsafe.

- Results: Google Translate was usually (> 90%) capable of safe and comprehensible translation from English to Spanish. Instructions with incresed complexity, especially regarding medications, were prone to unsafe translation. Back translation was not reliable in detecting unsafe Spanish.

- Conclusion: Google Translate is a continuously evolving resource for clinicians that offers the promise of improved physician-patient communication. Simple declarative sentences are most reliably translated with high quality and safety.

Keywords: translation; machine translation; electronic health record; after-visit summary; patient safety; physician-patient communication.

Acore measure of the meaningful use of electronic health records incentive program is the generation and provision of the after visit summary (AVS), a mechanism for physicians to provide patients with a written summary of the patient encounter [1,2]. Although not a required element for meaningful use, free text patient care instructions (PCIs) provide the physician an opportunity to improve patient engagement either at the time of service or through the patient portal [3] by providing a short written summary of the key points of the office visit based upon the visit’s clinical discussion. For patients who do not speak English, a verbal translation service is required [4], but seldom are specific patient instructions provided in writing in the patient’s preferred language. A mechanism to improve communication might be through translation of the PCI into the patient’s preferred language. Spanish is the most common language, other than English, spoken at home in the United States [5,6]. For this reason, we chose to investigate if it is feasible to use machine translation (Google Translate) to safely and reliably translate a variety of PCIs from English to Spanish, and to assess the types of translation errors and ambiguities that might result in unsafe communication. We further investigate if machine back translation might allow the author of patient care instructions to evaluate the quality of the Spanish machine translation.

There is evidence to suggest that patient communication and satisfaction will improve if portions of the AVS are communicated in Spanish to primarily Spanish-speaking patients. Pavlik et al conducted a randomized controlled trial on the association of patient recall, satisfaction, and adherence to the information communicated in an AVS, in a largely Hispanic (61%) primary care clinic setting [7]. The AVS was provided in English. They noted that Spanish speakers wished to receive information in Spanish, although most had access to translation by a family member. They also noted that a lack of ability to provide an AVS in Spanish was a concern among providers. There was no difference in recall or satisfaction between English and Spanish speakers with respect to medications and allergies, suggesting that not all portions of the AVS might need to be translated.

Machine translation refers to the automated process of translating one language to another. The most recent methods of machine translation, as exemplified by Google Translate (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA), do not use rules of grammar and dictionaries to perform translations but instead use artificial neural networks to learn from “millions of examples” of translation [8]. However, unsupervised machine translation can result in serious errors [9]. Patil gives as an example of a serious error of translation from English (“Your child is fitting”) to Swahili (“Your child is dead”). In British parlance, “fitting” is a term for “having a seizure” and represents an example of a term that is context sensitive. However, others note that there is reason to be optimistic about the state of machine translation for biomedical text [10].

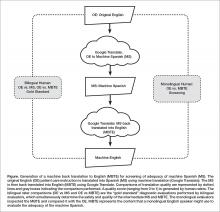

One method of assessing translation quality is through back translation, where one translator takes the author’s work into the desired target language, and then a different translator takes the target language back to the language of the author. Like the children’s game Chinese Whispers (Telephone in the United States) [11], where a “secret message” is whispered from one child to the next and spoken aloud at the end of the line of children, back translation can test to see if a message “gets through.” In this analogy, when information is machine translated from English to Spanish, and then machine translated from Spanish to English (Figure), we can compare the initial message to the final translation to see if the message “gets through.” We further investigate if machine back translation might allow a non-Spanish speaking author of PCIs to evaluate the quality of the Spanish translation.

Our intention was to determine if machine back translation [12] could be used by an English-only author to assess the quality of an intermediate Spanish translation. If poorly worded Spanish translated back into poorly worded English, the author might choose to either refine their original message until an acceptable machine back translation was achieved or to not release the Spanish translation to the patient. We were also concerned that there might be instances where the intermediate Spanish was unacceptable, but when translated back into English by machine translation, relatively acceptable English might result. If this were the case, then back translation would fail to detect a relatively poor intermediate Spanish translation.

Methods

Patient Care Instructions

Original English PCIs

Example original English PCIs were solicited from the clinical faculty and resident staff of the University of Arizona College of Medicine by an email-based survey tool (Qualtrics, Inc, Provo UT). The solicitation stated the following:

We are conducting a study to assess how well Google Translate might perform in translating patient instructions from English to Spanish. Would you please take the time to type three sentences that might comprise a typical “nugget” of patient instruction using language that you would typically include in an After Visit Summary for a patient? An example might be: “Take two Tylenol 325 mg tablets every four hours while awake for the next two days. If you have a sudden increase in pain or fever, or begin vomiting, call our office. Drink plenty of fluids.”

A total of 100 PCIs were collected. The breadth of the clinical practice and writing styles of a College of Medicine faculty are represented: not all were completely clear or were well-formed sentences, but did represent examples provided by busy clinicians of typical language that they would provide in an AVS PCI.

Machine Translation into Spanish

The 100 original English (OE) PCIs were submitted to the Google Translate web interface (https://translate.google.com/) by cutting and pasting and selecting “Spanish,” resulting in machine Spanish. The translations were performed in January 2016. No specific version number is provided by Google on their web page, and the service is described to be constantly evolving (https://translate.google.com/about/intl/en_ALL/contribute.html).

Machine Back Translation into English (MBTE)

Google Translate was then used to translate the machine Spanish back into into English. MBTE represents the content that a monolingual English speaker might use to evaluate the machine Spanish.

Ratings of Translation Quality and Safety

Two panels of 6 raters evaluated machine Spanish and MBTE quality and safety. A bilingual English/Spanish speaking panel simultaneously evaluated the machine Spanish and MBTE compared to OE, with the goal of inferring where in the process an undesirable back translation error occurred. Bilingual raters were experienced bilingual clinicians or certified translators. A monolingual English speaking panel also evaluated the MBTE (compared to OE). They could only infer the quality and safety of the machine Spanish indirectly through inspection of MBTE, and their assessment was free of the potential bias of knowledge of the intermediate Spanish translation.

The raters used Likert scales to rate grammar similarity and content similarity (scale from 1 to 5: 1 = very dissimilar, 5 = identical). For each PCI, grammar and content scores for each rater were summed and then divided by 10 to yield a within-rater quality score ranging from 0 to 1. A panel-level (bilingual or monolingual) quality score was calculated by averaging the quality scores across raters.

Safety of translation was rated as 0 or Safe (“While the translation may be awkward, it is not dangerous” or 1 or Unsafe (“A dangerous translation error is present that might cause harm to the patient if instructions were followed”). If any panel member considered an item to be unsafe, the item as a whole was scored as unsafe.