Tools and Team Support

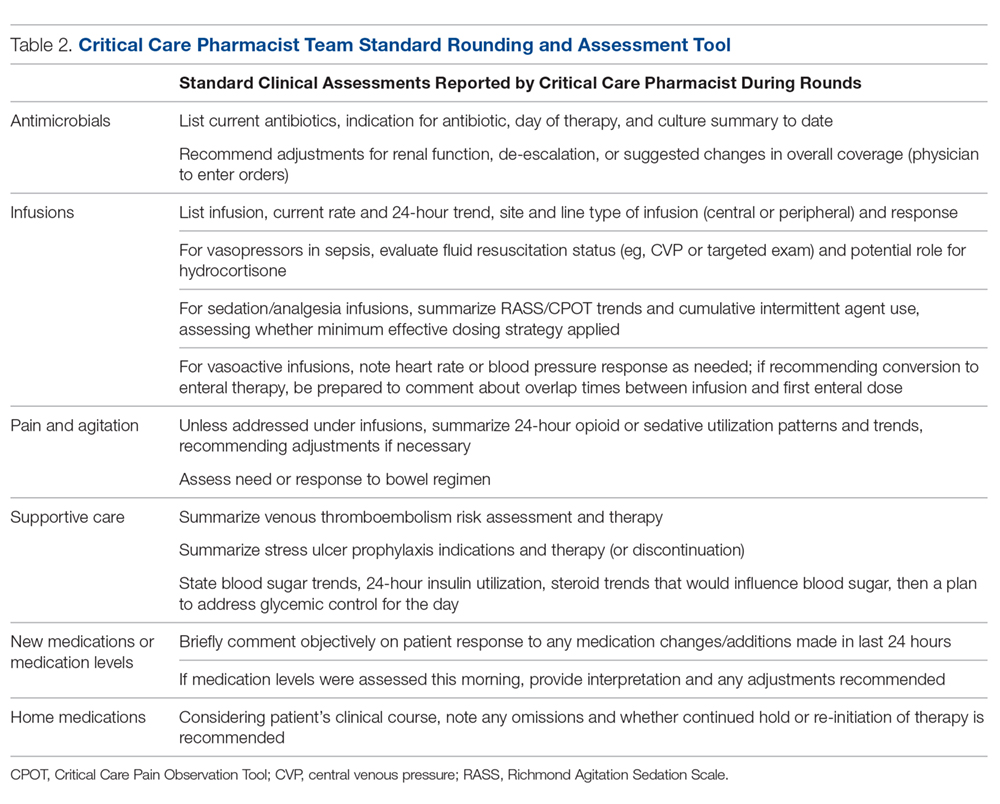

Beyond standardizing knowledge and skills, team effectiveness depended on establishing routine assessment criteria (Table 2), communication tools, and references. Rounding and sign-out processes were standardized to support continuity of care. A patient census report generated by the clinical computer system was used as the daily worksheet and was stored on a sign-out clipboard to readily communicate clinically pertinent history, assessments, recommendations, and pending follow-up. The report included patient demographics, admitting diagnosis, and a list of consulting physicians. The pharmacist routinely recorded daily bedside observations, his/her independent assessments (topics outlined in Table 2), pertinent history, events, and goals established on rounds. Verbal sign-out occurred twice daily (during weekdays)—from the rounding to satellite pharmacist after rounds (unless 1 person fulfilled both roles) and between day and evening shifts. Additionally, a resource binder provided rapid accessibility to key information (eg, published evidence, tools, institutional protocols), with select references residing on the sign-out clipboard for immediate access during rounding.

Monthly meetings were established to promote full engagement of the team, demonstrate ownership, and provide opportunity for discussion and information sharing. Meetings covered operational updates, strategic development of the service, educational topics, and discussions of difficult cases.

Assessment

While not directly studied, existing evidence suggests that appropriately trained critical care pharmacists should be able to perform a broad range of services, from fundamental to optimal.7 To evaluate if CCPT training elevated and standardized the type of interventions routinely made, services provided prior to the team’s formation were compared to those provided after formation through interrogation of the institution’s surveillance system. As a baseline, a comparison of the types of ICU interventions documented by the specialist during a 2-month period prior to the team’s formation were compared to the interventions documented by the staff pharmacists who became part of the CCPT. Since standardization of skills and practice were goals of the CCPT formation, the same comparison was conducted after team formation to assess whether the intervention types normalized across roles, reflecting a consistent level of service.

As assignment to the CCPT is voluntary, with no additional compensation or tangible benefits, the success of the CCPT relies on active pharmacist engagement and ongoing commitment. Thus, a personal belief that their commitment was valuable and increased professional satisfaction was key to sustain change. An online, voluntary, anonymous survey was conducted to assess the CCPT member’s perceptions of their preparedness, development of skills and comfort level, and acceptance by the multidisciplinary team, as these elements would influence members’ beliefs regarding the impact and value of the team and their justification for commitment to continuous, uncompensated learning and training. Their thoughts on professional satisfaction and development were collected as a surrogate for the model’s sustainability.

Success and sustainability also depend on the multidisciplinary team’s acceptance and perceived value of the CCPT, especially given its evolution from a model in which clinical feedback was sought and accepted exclusively from the specialist. To evaluate these components, an online, voluntary, anonymous survey of the multidisciplinary members was conducted.