Discussion

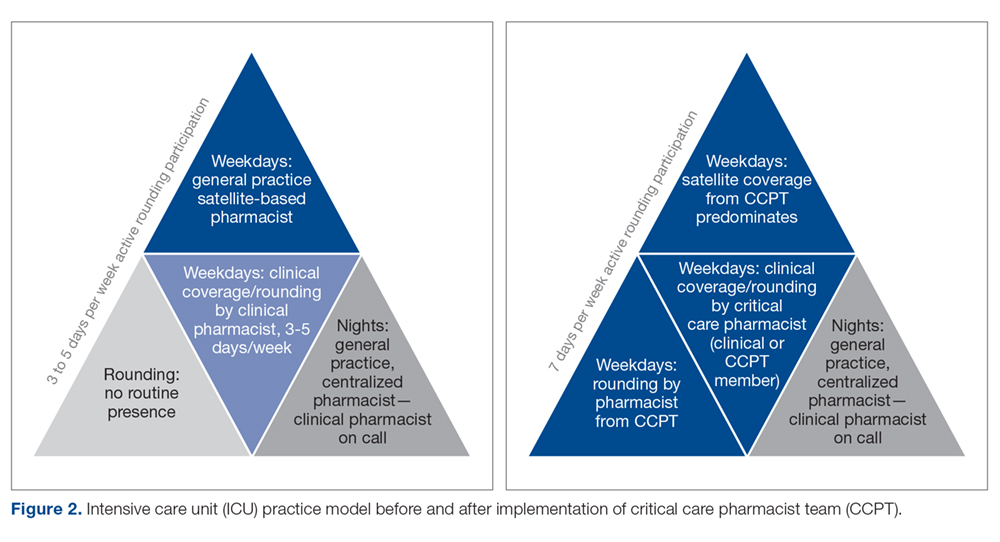

Realignment and development of existing personnel resources allowed our organization to assure greater continuity, consistency, and quality of pharmacy care in the critical care setting (Figure 2). By standardizing expectations and broadening multidisciplinary understanding of the CCPT’s unique value, the pharmacist’s role was solidified and became an integral, active part of routine patient bedside care.

Prior to forming the CCPT, the physical presence of the pharmacist, as well as the services provided, were inconsistent. While a general practice pharmacist was in the satellite pharmacy within the ICU for up to 2 shifts on weekdays, pharmacists largely focused on traditional functions associated with order review and drug dispensing or established hospital-wide programs such as renal dosing or intravenous-to-oral formulation switches. The pharmacist remained in the satellite, not visible on rounds or at the bedside. In fact, there was a clear lack of comfort, frequently articulated by the pharmacists, with clinical questions that required bedside assessment, leading to routine escalation to the clinical specialist, who was not always readily available. This dynamic set an expectation for the multidisciplinary team that there were segregated pharmacy services—the satellite provided order review and product and the clinical specialist, in the limited hours present, provided clinical consultation and education. The formation of the CCPT abolished this tiered level of expectations, establishing a physical and clinical presence of a critical care pharmacist with equal capability and comfort. Both the pharmacist and multidisciplinary members perceived enhancements and value associated with the standardization and consistency provided by implementing the CCPT. Intervention data from before and after team formation support that routine interventions in critical care normalized the care provided and increased the robustness of critical care pharmacy services, with a strong shift to both clinical and academic activities considered desirable to optimal by SCCM/ACCP standards.

The benefit of pharmacist presence in the ICU is well described, with studies showing that the presence of a pharmacist is associated with medication error prevention and adverse drug event identification.8-10 However, this body of evidence applies no standardized definition regarding critical care pharmacist qualifications, with many studies pre-dating the wider availability of post-doctoral training programs and national board certification for critical care pharmacists.11 Training and certification structures have evolved with increased recognition of the specialization required to optimize the pharmacist’s role in providing quality care, albeit at a slower pace than published standards.1,2 In 2018, 136 organizations offered America Society of Health-System Pharmacists–accredited critical care pharmacy residencies.12 National recognition of expertise as a critical care pharmacist was established by the Board of Pharmacy Specialists in 2015, with more than 1600 pharmacists currently recognized.12 Our project is the only known description of a pharmacist practice model that increases critical care pharmacist availability through the application of standardized criteria incorporating these updated qualifications, thus ensuring expertise and experience that correlates with practice quality and consistency.

Despite the advancements achieved through this project, several limitations exist. First, while this model largely normalized services over the day and evening shifts, our night shift continues to be covered by 1 general practice pharmacist. More recently, resource reallocation mandated reduction in satellite hours, although that CCPT member remains available from the main pharmacy. The specialist remains on call to support the general practice pharmacists, but in-house expertise cannot be made available in the absence of additional resources. To optimize existing staffing, the specialist begins clinical evaluations during the early morning, overlapping with the night-shift prior to the satellite pharmacist’s arrival. This both provides some pharmacist presence at the bedside for night shift nurses and extends the hours during which a critical care pharmacist is physically available. Second, while all efforts are made to stagger time off, unavoidable gaps in critical care pharmacist coverage occur; expansion of the original team from 3 to 6 members has greatly reduced the likelihood of such gaps. Last, the program was designed to achieve routine integration of activities shown in the literature as being associated with quality, and those activities were assessed as a surrogate for quality.

Informal input, confirmed through survey data, from various disciplines on our team has consistently supported that the establishment of the CCPT has met a need by both standardizing critical care pharmacy practice and optimizing the pharmacist role within the team. While we recognize the limitations associated with the size of these surveys, they represent large proportions of our team and reflect key elements known to be important in sustaining long-term cultural change—a belief that what one is doing is both justified and valuable. This success has been a catalyst for several ongoing projects, fostering the development and adoption of critical care pharmacist protocols to allow more autonomous practice within our scope. Team development and movement toward robust protocol management has sparked a cultural evolution across disciplines as we strive to achieve the SCCM description of a highly effective team2,13 that emphasizes each discipline practicing fully within its scope in a horizontal team structure. Thus, the ICU medical director has used the success of the CCPT structure as an example to support optimization and development of the practice by other disciplines within the team. This has led to a significant revision in our rounding structure and interdisciplinary care model.14