Results

Over the study period, there were 6424 unique patient admissions on the general internal medicine service, with a median LOS of 3.5 days (Table).

The majority of inpatient visits had at least 1 test of CBC (80%; mean, 3.6 tests/visit), creatinine (79.3%; mean, 3.5 tests/visit), or electrolytes (81.6%; mean, 3.9 tests/visit) completed. In total, 56,767 laboratory tests were ordered.

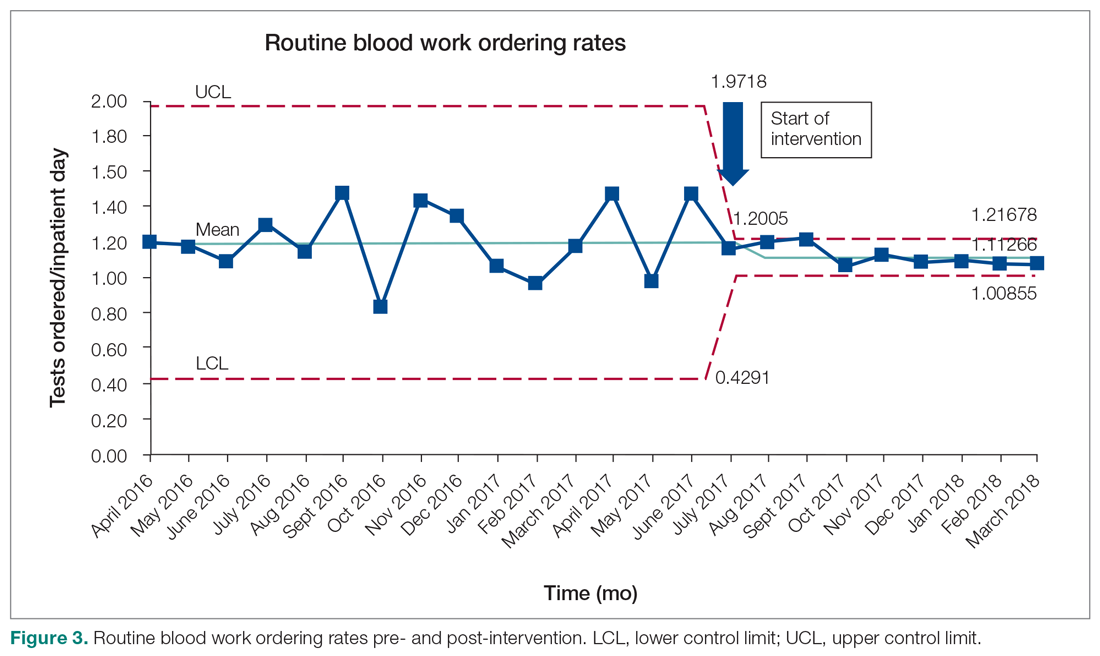

Following the intervention, there was a reduction in both rates of routine blood test orders and their associated costs, with a shift below the mean. The mean number of tests ordered (combined CBC, creatinine, and electrolytes) per inpatient day decreased from 1.19 (SD, 0.21) in the pre-intervention period to 1.11 (SD, 0.05) in the post-intervention period (P < 0.0001), representing a 6.7% relative reduction (Figure 3). We observed a 6.2% relative reduction in costs per inpatient day, translating to a total savings of $26,851 over 1 year for the intervention period.

Discussion

Our study suggests that a multimodal intervention, including CPOE restrictions, resident education with posters, and audit and feedback strategies, can reduce lab test ordering on general internal medicine wards. This finding is similar to those of previous studies using a similar intervention, although different laboratory tests were targeted.1,2,5,6,10,17

Our study found lower test result reductions than those reported by a previous study, which reported a relative reduction of 17% to 30%,18 and by another investigation that was conducted recently in a similar setting.17 In the latter study, reductions in laboratory testing were mostly found in nonroutine tests, and no significant improvements were noted in CBC, electrolytes, and creatine, the 3 tests we studied over the same duration.17 This may represent a ceiling effect to reducing laboratory testing, and efforts to reduce CBC, electrolytes, and creatinine testing beyond 0.3 to 0.4 tests per inpatient day (or combined 1.16 tests per inpatient day) may not be clinically appropriate or possible. This information can guide institutions to include other areas of overuse based on rates of utilization in order to maximize the benefits from a resource intensive intervention.

There are a number of limitations that merit discussion. First, observational studies do not demonstrate causation; however, to our knowledge, there were no other co-interventions that were being conducted during the study duration. One important note is that our project’s intervention began in July, at which point there are new internal medicine residents beginning their training. As the concept of resource allocation becomes more important, medical schools are spending more time educating students about Choosing Wisely, and, therefore, newer cohorts of residents may be more cognizant of appropriate blood testing. Second, this is a single-center study, limiting generalizability; however, we note that many other centers have reported similar findings. Another limitation is that we do not know whether there were any adverse clinical events associated with blood work ordering that was too restrictive, although informal tracking of STAT laboratory testing remained stable throughout the study period. It is important to ensure that blood work is ordered in moderation and tailored to patients using one’s clinical judgment.

Future Directions

We observed modest reductions in the quantity and costs associated with a quality improvement intervention aimed at reducing routine blood testing. A baseline rate of laboratory testing of less than 1 test per inpatient day may require including other target tests to drive down absolute utilization.

Corresponding author: Christine Soong, MD, MSc, 433-600 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5G 1X5; Christine.soong@utoronto.ca.

Financial disclosures: None.