Pharyngitis patients have disproportionately higher odds of receiving a GAS test in most regions of the country compared to the Pacific region. For instance, children in the Mid-Atlantic region have 51% higher odds of receiving a GAS test while children in New England have 80% higher odds of receiving the same test.

Black children have 11% lower odds of receiving the GAS test compared to White children. Both middle-income and high-income children have 12% and 32% higher odds of receiving the test compared to low-income children. Compared to office-based visits, children visiting a clinic were twice as likely to receive a GAS test while those seen in the emergency room have 43% lower odds of receiving a GAS test. Hospital outpatient departments, which account for less than 1% of all visits, rarely used a GAS test which could be a statistical artifact due to small sample size. Lastly, insurance and season of the year had no significant impact of receipt of a GAS test.

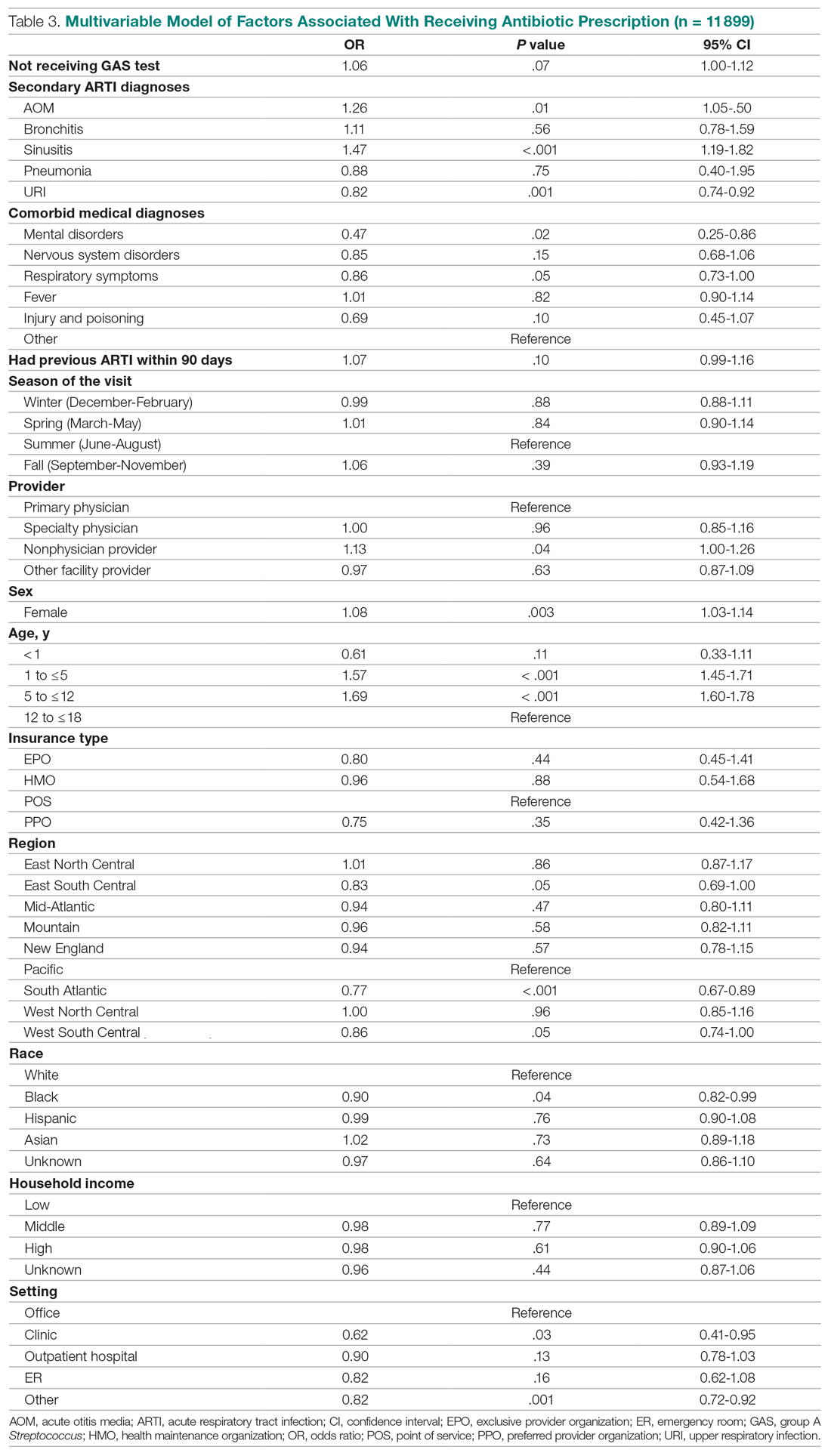

Factors associated with receiving antibiotic prescription

Surprisingly, receiving the GAS test has a small but insignificant impact on the likelihood that the patient will receive an antibiotic prescription (Table 3) (Adjusted OR = 1.055, P = .07). After controlling for receipt of a GAS test, children with AOM and sinusitis comorbidities have an increased likelihood of being prescribed an antibiotic. Children with URI have a lower likelihood of being prescribed an antibiotic. Additionally, relative to primary care physicians, children visiting nonphysician providers for pharyngitis were more likely to be prescribed an antibiotic.

Children under 12 years of age were more likely to use an antibiotic compared to children 12 years and older. Geographically, there is some evidence of regional variation in antibiotic use as well. Children in the south Atlantic, west-south central, and southeast central regions had a significantly lower odds of being prescribed an antibiotic respectively than pharyngitis patients in the Pacific region. Black children had a 10% lower likelihood of being prescribed an antibiotic compared to White children, possibly related to their lower rate of GAS testing. Compared to office-based visits, children visiting a clinic were less likely to use an antibiotic. Household income, insurance type, and season had no significant impact on revisit risk.

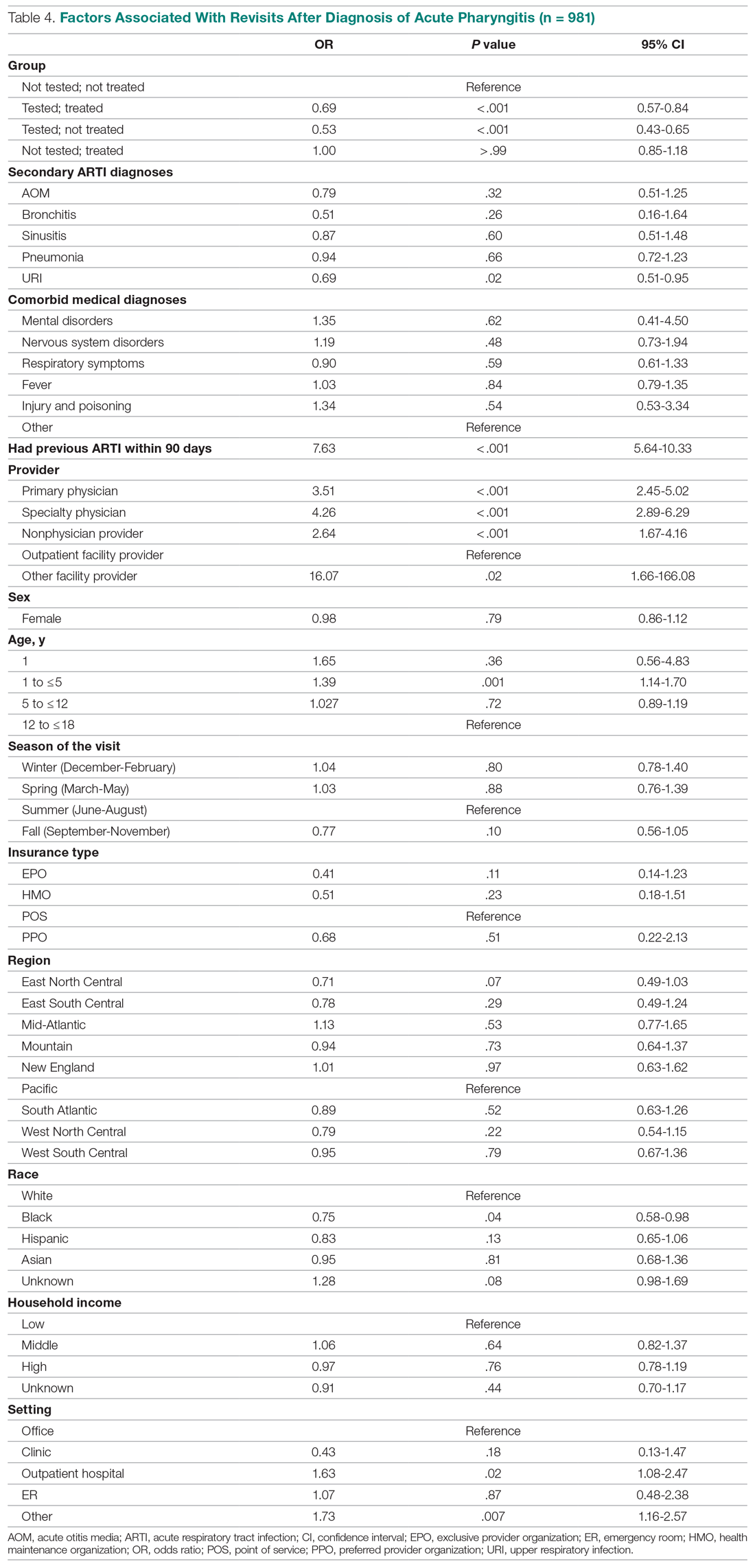

Effects of GAS test and antibiotic prescriptions on likelihood of revisits

The multivariate analysis of the risk of a revisit within 28 days is presented in Table 4. Children with pharyngitis who tested and did not receive an antibiotic serve as the reference comparison group for this analysis to illustrate the impact of using the GAS test and treatment with an antibiotic. The results in Table 4 are quite clear: patients who receive the GAS test were significantly less likely to have a revisit within 28 days. Moreover, within the group of patients who were tested, those not receiving an antibiotic, presumedly because their GAS test was negative, experienced the lowest risk of a revisit. This result is consistent with the data in Table 1. Moreover, using an antibiotic had no impact on the likelihood of a revisit in patients not receiving the GAS test. This result is also consistent with Table 1.