GLASGOW – People with giant cell arteritis may be more likely to go blind if they have underlying vascular disease, according to an analysis of the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study.

The results of the analysis showed that 7.9% of patients with this common type of vasculitis go blind in at least one eye within 6 months of a diagnosis, and that those with a history of peripheral vascular disease (PVD) could be up to 10 times more at risk than those without additional vascular comorbidity.

“This is the first multinational study for patients with [giant cell arteritis], and it shows that blindness is a significant problem,” said Dr. Max Yates of the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, who presented the findings at the British Society for Rheumatology annual conference. Blindness was defined as complete visual loss rather than by a full ophthalmology assessment, so the findings probably underplay the problem in patients with some form of visual loss, he observed. Visual disturbance had been noted in 42.9% of the patients who were studied at the first clinic review.

“It is interesting that there is the association with vascular disease,” Dr. Yates said. “Perhaps we need greater vigilance in those people who already have a diagnosis of vascular disease [and] to really watch and monitor those people carefully for sight loss.”

The Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS) is an ongoing project designed to develop and then validate new classification and diagnostic criteria for systemic vasculitis that can be used routinely in clinical practice and in clinical trials. So far, more than 3,500 participants over age 18 have been recruited from secondary care clinics, and of those, 2,000 have a new or established diagnosis of vasculitis. The others have a similar presentation but an alternative diagnosis.

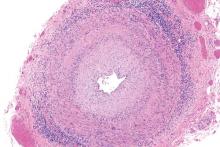

A total of 433 patients participating in the DCVAS were identified as having GCA with more than 75% diagnostic certainty, of which 93% fulfilled the 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA and just over half (54%) had a positive temporal artery biopsy. Visual loss was recorded by completion of the Vasculitis Damage Index (VDI) 6 months after diagnosis.

Two-thirds of patients studied were female, the median age at diagnosis was 73 years, 40% had jaw claudication, 34% had lost weight, and 16% presented with a fever. In addition, 9.2% had diabetes, 3.2% a prior stroke, and 2.5% had PVD.

Looking for predictive factors, baseline laboratory findings such as the presence of anemia, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, or platelet counts were not associated with sight loss. Dr. Yates noted in discussion that the baseline ESR range was 35-120 mm/h and the CRP ranged from 12 to over 100 mg/dL in the patients studied.

However, prior vascular disease was found to be predictive of later blindness. The odds ratio (OR) for being blind in at least one eye 6 months after a GCA diagnosis was 10.44 for PVD, with the 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 2.94 to 37.03. A prior diagnosis of cerebral vascular accident (OR, 4.47; 95% CI, 1.30-15.41), and diabetes (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 0.98-6.25) also upped the risk for complete sight loss at 6 months.

Dr. Yates noted that patients were selected from multiple clinics across secondary care, so there should be better generalizability than in prior, single-center studies. However, there could be some residual referral bias.

During discussion, it was pointed out that it would be helpful to know the rate of blindness in patients taking steroids, as this was one of the major reasons for emergency rheumatology calls at one clinic, a delegate observed.

“Giant cell arteritis is really the major rheumatology emergency for practicing clinicians. We recently set up a rheumatology day service and get usually 8-10 calls about it per day,” the delegate said. “It’s often said that once a patient is on any dose of steroids, there is not risk of them going blind.” There is a lot of angst about whether it is safe to use higher doses (60 mg vs. 40 mg) and “it’s important for us as clinicians to be able to reassure people.”

Dr. Yates noted that a prospective trial would be needed to answer the question and that trials were planned. “We don’t have any data on treatment,” he said. “So we’re unable to say whether steroids were started instantly or whether there was any improvement in the visual function of these people.” Long-term complications also would be something to look at, particularly in older people who have an increased risk for eye problems such as cataracts, and could be at higher risk for visual problems if treated with steroids or other agents.