News for Your Practice

What you should know about the latest change in mammography screening guidelines

When the American Cancer Society issued new guidelines, key stakeholders responded with a “Yay” or “Nay”—and sometimes both. How should you...

Dr. Kopans is Professor of Radiology at Harvard Medical School and Senior Radiologist in the Breast Imaging Division at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

Dr. Kopans reports that he receives grant or research support from General Electric and is a consultant to General Electric and Hologic. Massachusetts General Hospital holds his patent on digital breast tomosynthesis.

If women wait until age 45 to begin annual screening, then shift to biennial screening at age 55, more than 38,000 women now in their 40s will die unnecessarily

With the recent publication of new American Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines on breast cancer screening,1 we finally have achieved a consensus. All major organizations, including the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), agree that the most lives are saved by annual screening beginning at age 40. This is the only science-backed finding of their reviews.

Here is a statement from the USPSTF: “[We] found adequate evidence that mammography screening reduces breast cancer mortality in women ages 40 to 74 years.”2 And from the ACS: “Women should have the opportunity to begin annual screening between the ages of 40 and 44 years.”1

Regrettably, the USPSTF, whose guidelines determine insurance coverage, endangers women by going on to suggest that they can wait until the age of 50 to begin screening and then wait a full 2 years between screens.

The new ACS guidelines have been misreported as recommending the initiation of annual screening at age 45, moving to biennial screening at the age of 55. This misunderstanding arose because the ACS describes annual screening starting at age 40 as a “qualified recommendation.” However, it defines this qualified recommendation as meaning that “The majority of individuals in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not.”1

Why would screening guidelines be based on “what many [women] would not” choose? No one forces women at any age to participate in screening. Each woman, regardless of age, should choose for herself whether or not to participate in screening. In fact, the ACS panel provides no data on what screening option women would prefer. Members of the ACS and USPSTF panels, none of whom provides care for women with breast cancer, injected their own personal biases to qualify what the scientific evidence shows by claiming to have “weighed” benefits against “harms.” Yet they provide no description of the scale that was used. They state only that there are 2 major harms: “false positives” and “overdiagnosis.”

“False positive” is a misnomerRecalls from screening have been called, pejoratively, “false positives,” leading some to believe that women are being told that they have breast cancer when they do not. In reality, most recalled women ultimately are told that there is no reason for concern.

Approximately 10% of US women who undergo screening mammography are recalled—the same percentage as for Pap testing.3 (The ACS and USPSTF panels ignore the benefit for the 90% of women who are reassured by a negative screen.)

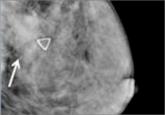

Among the women recalled, more than half are told that everything is fine, based on a few extra pictures or an ultrasound. Approximately 25% (2.5% of those screened) are asked to return in 6 months just to be careful, and approximately 20% (2% of women screened) will be advised to undergo imaging-guided needle biopsy using local anesthesia. Among these women, 20% to 40% will be found to have cancer.4

This figure is much higher than in the past, when women had “lumps” surgically removed, only 15% of which were cancer. Most of these lesions were larger and less likely to be cured than screen-detected cancers.5

Panels fail to justify breast cancer deaths that would occur with proposed screening intervalsThe main reason the ACS and USPSTF panels decided to compromise on their recommendations was to try to reduce the number of recalls, yet they never explain how many fewer recalls are equivalent to allowing a death that could have been avoided by annual screening starting at age 40.

The National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET)—used by both panels—shows that, if women in their 40s wait until age 50 and then are screened every 2 years (as the USPSTF recommends), as many as 100,000 lives will be lost that could have been saved by annual screening starting at age 40.6 If women wait until age 45 to begin annual screening and then shift to biennial screening at age 55 (as the ACS recommends), more than 38,000 women now in their 40s will die, unnecessarily, as a result.7

Neither panel states how many recalls avoided are equivalent to allowing so many avoidable, premature deaths.

No invasive cancers resolve spontaneouslyThe other alleged harm of screening is “overdiagnosis”—the exaggerated suggestion that mammography screening finds tens of thousands of breast cancers each year that, if left undetected, would disappear on their own.8,9 Such analyses have been shown to be scientifically unsupportable.10–13 In fact, no one has ever seen an invasive breast cancer disappear on its own without therapy. The claim is tens of thousands each year, yet no one has seen a single case.

There certainly are legitimate questions about the need to treat all cases of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). However, if an invasive breast cancer is found during screening and then left alone, it will grow to become a palpable cancer, with lethal capability.

When the American Cancer Society issued new guidelines, key stakeholders responded with a “Yay” or “Nay”—and sometimes both. How should you...

Confused about which guidelines for breast cancer screening to follow in average-risk women? ACOG takes action with an upcoming consensus...

An expert radiologist and dense breast educators address specific questions that will arise in your counseling and care of women who are...

What will you tell your patient who asks about the clinical significance of dense breasts detected on her mammogram? Here I offer my current...