Multimodal approach to pain management

The goals of postsurgical pain treatment are to relieve suffering, optimize bodily functioning after surgery, limit length of the stay, and optimize patient satisfaction. Pain-control regimens should consider the specific surgical procedure and the patient’s medical, psychological, and physical conditions; age; level of fear or anxiety; personal preference; and response to previous treatments.10

Optimally, postsurgical pain management starts well before the day of surgery. Employing such strategies as Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) protocols does not necessarily mean providing the same care for every patient, every time. Rather, ERAS serves as a checklist to ensure that all applicable categories of pain medication and pain-control strategies are considered, selected, and dosed according to individual needs.11 (See “Preoperative management of pain expectations.”)

Ideally, before surgery, provide the patient with an opportunity to learn that:

- Her expectations about postsurgical pain should be realistic, and that freedom from pain is not realistic.

- Pain-reduction options should optimize her bodily function and mobility, reduce the degree to which pain interferes with activities, and relieve associated psychological stressors.

- Inherent in the pain management plan should be a goal of minimizing the risks of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction—for the patient and for her family members and friends.

Opioids

Opioids have been employed to treat pain for 700 years.12 They are powerful pain relievers because they target central mechanisms involved in the perception of pain. Regrettably, because of their central action, opioids have many adverse effects in addition to being highly addictive.

Nonopioid alternatives

Expert consensus, including recommendations of the World Health Organization,11 favors using nonopioids as first-line medications to address surgical pain. Nonopioid analgesic options are acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and adjuvant medications. In addition, nonanalgesic medications such as sedatives, sleep aids, and muscle relaxants can relieve postsurgical pain. Optimal use of these nonopioid medications can significantly reduce or eliminate the need for opioid medications to treat pain. Goals are to 1) reserve opioids for the most severe pain and 2) minimize the number of doses/pills of opioids required to control postsurgical pain.

Acetaminophen. At dosages of 325 to 1,000 mg orally every 4 to 6 hours, to a maximum dosage of 4,000 mg/d, acetaminophen can be used to treat mild pain and, in combination with other medications, moderate-to-severe pain. The drug also can be administered intravenously (IV), although use of the IV route is limited in many hospitals because of its significantly higher expense compared to the oral form.

The mechanism of action of acetaminophen is unique among pain relievers; it can therefore be used in combination with other pain relievers to more effectively treat pain with fewer concerns about medication-induced adverse effects or opioid overdose. However, keep in mind when considering combining analgesics, that acetaminophen is an active ingredient in hundreds of over-the-counter (OTC) and prescription formulations, and that a combination of more than one acetaminophen-containing product can create the risk of overdose.

Acetaminophen should be used with caution in patients with liver disease. That being said, multiple trials have documented safe use in normal body weight adults who do not have hepatic disease, at dosages as high as 4,000 mg over a 24-hour period.13

NSAIDs. A combination of an NSAID and acetaminophen has been documented to reduce the amount of opioid medications required to treat postsurgical pain. In most circumstances, especially for minor surgery, acetaminophen and NSAIDS can be administered just before surgery starts. This preoperative treatment, called “preventive analgesia” or “preemptive analgesia,” has been demonstrated in multiple clinical trials to reduce postoperative pain.14

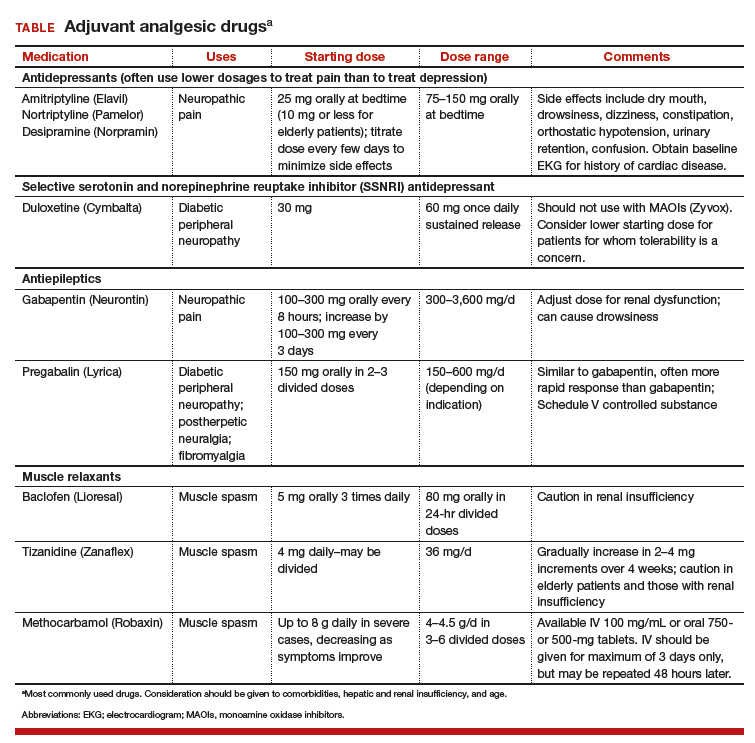

Adjuvant pain medications. Antidepressants, antiepileptic agents, and muscle relaxants—agents that have a primary indication for a condition (or conditions) other than pain and do not directly provide analgesia—have been used as adjuvant pain medications. When employed with traditional analgesics, they have been demonstrated to reduce postsurgical pain scores and the amount of opioids required. These medications need to be used cautiously because some are associated with serious sedation and vertigo (TABLE). Take caution when using adjuvant pain medications in patients older than 65 years; guidance on their use in older patients has been outlined by the American Geriatrics Society and other professional organizations.15

Case Continued

The patient was given the expectation that the 11-mm left lower-quadrant port site would likely be the most bothersome site of pain—a rating of 4 or 5 on a visual analogue scale of 1 to 10, on postoperative day 1, while standing. The other 3 (5-mm) laparoscopic ports, she was told, would, typically, be less bothersome. The patient was educated regarding the role of analgesics and adjuvant medications and cautioned not to exceed 4,000 mg of acetaminophen in any 24-hour period. She was told that gabapentin may make her feel sedated or dizzy, or both; she was encouraged to hold this medication if she found these adverse effects bothersome or limiting.

The following multimodal pain management was established.

Preoperatively, the patient was given:

- Acetaminophen 1.5 g orally (as a liquid, 45 mL of a suspension of 500 mg/15 mL liquid), 2 to 3 hours preoperatively; the surgical suite did not stock IV acetaminophen.

- Gabapentin 600 mg orally, with a sip of water, the morning of surgery.

- Celecoxib 100 mg orally, with a sip of water, the morning of surgery.

Prescriptions for home postoperative pain management were provided preoperatively:

- OTC acetaminophen 1,000 mg (as 2 500-mgtablets) taken as a scheduled dose every 8 hours for the first 48 hours postoperatively.

- Meloxicam 15 mg daily as the NSAID, taken as a scheduled dose once per day for the first 48 hours postoperatively, then as needed.

- Gabapentin 300 mg (in addition to the preoperative dose, above), taken as a scheduled dose every 8 hours for the first 48 hours postoperatively, then as needed.

- Oxycodone 5 mg (without acetaminophen) for breakthrough pain.

Intraoperatively:

- Meticulous attention was paid to patient positioning, to reduce the possibility of back and upper- and lower-extremity injury postoperatively.

- A corticosteroid (dexamethasone 8 mg IV) was administered to minimize postoperative nausea and vomiting and as an adjuvant medication for postoperative pain control.

- Careful attention was paid to limit residual CO2 gas and intraoperative intra-abdominal pressures.

- All laparoscopic port sites were injected with 30 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine, extending to subcutaneous, fascial, and peritoneal layers.

Read about why a multimodal approach is best for postsurgical pain.